The architect Erich Mendelsohn’s work seemed to define the spirit of the modern world in the Weimar Republic and 1920s Berlin. A current exhibition of his sketches reflects the extraordinary fertility and vitality of this architect’s vision, which continued even after he had to leave his whole life and practice in Germany behind with the coming of the Nazis. uncube’s Rob Wilson visited and considers how these drawings compare favourably with today’s computer visualisations – and touch on genius.

Erich Mendelsohn (1887-1953) was the author of some of the most instantly recognizable buildings of the 1920s: from the extraordinary organic expressionism of the Einstein Tower observatory in Potsdam to the dramatic horizontal curving lines of the Schocken Department store chain across Germany.

His buildings seemed to perfectly capture the mood of the moment, expressing in graphic new forms the strange and exciting world of modernity emerging after the First World War. And nowhere was change or the hunger for novelty more extreme than in 1920s Berlin, where Mendelsohn’s practice was based. The third largest city in the world at the time, and still expanding rapidly, was the crucible of intense artistic, social and technological developments during the years of the Weimar Republic: from the biting social critique of the New Objectivity movement in the plays of Bertolt Brecht and art of George Grosz, to Magnus Hirschfeld’s sexology institute and Albert Einstein’s work at Humboldt University, and Europe’s first traffic lights, installed at Potsdamer Platz, the busiest traffic junction in the world. Berlin was a city on speed.

And Mendelsohn himself seems a man possessed in the 1920s, building up his practice almost from scratch to become the largest architects’ office in Germany by the end of the decade. Whilst Le Corbusier was still just polemicising about new modernist cities, Mendelsohn was getting on and building large chunks of them, from offices, to housing, cinemas and factories, and not just across Germany but in Russia too.

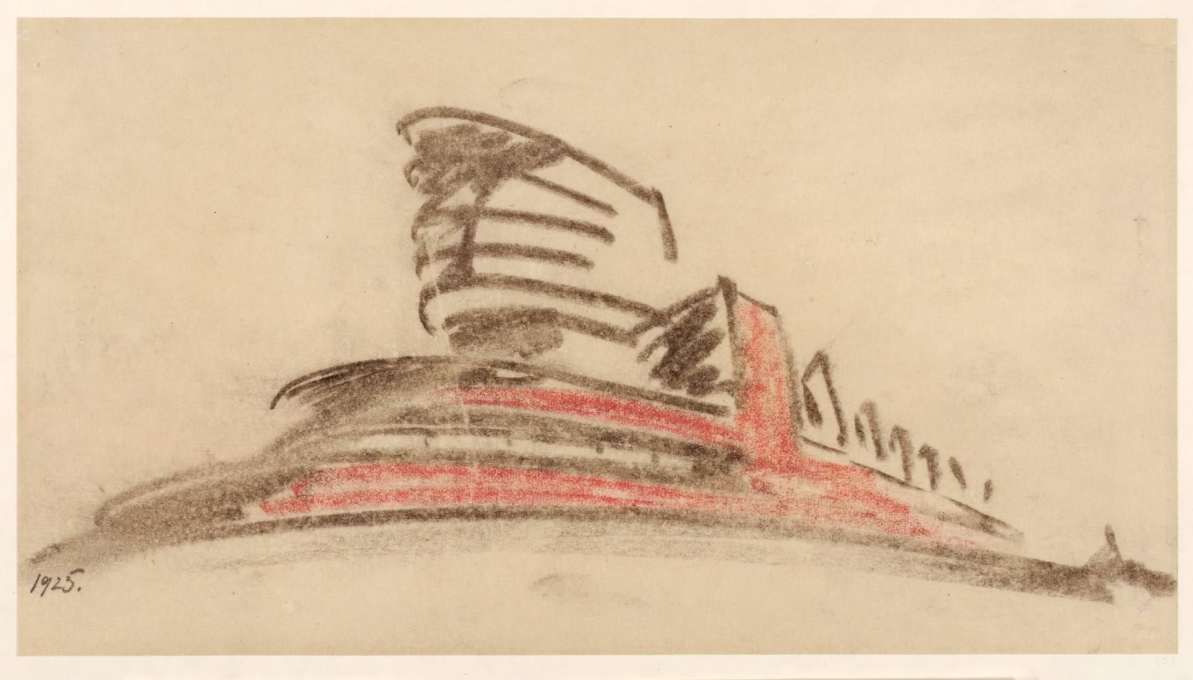

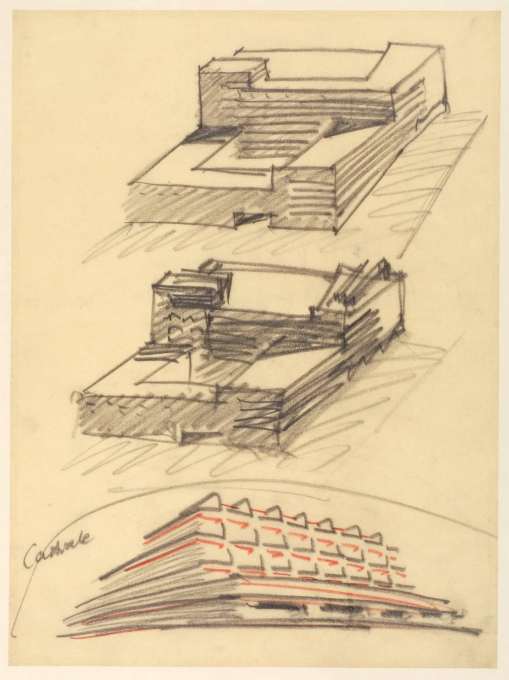

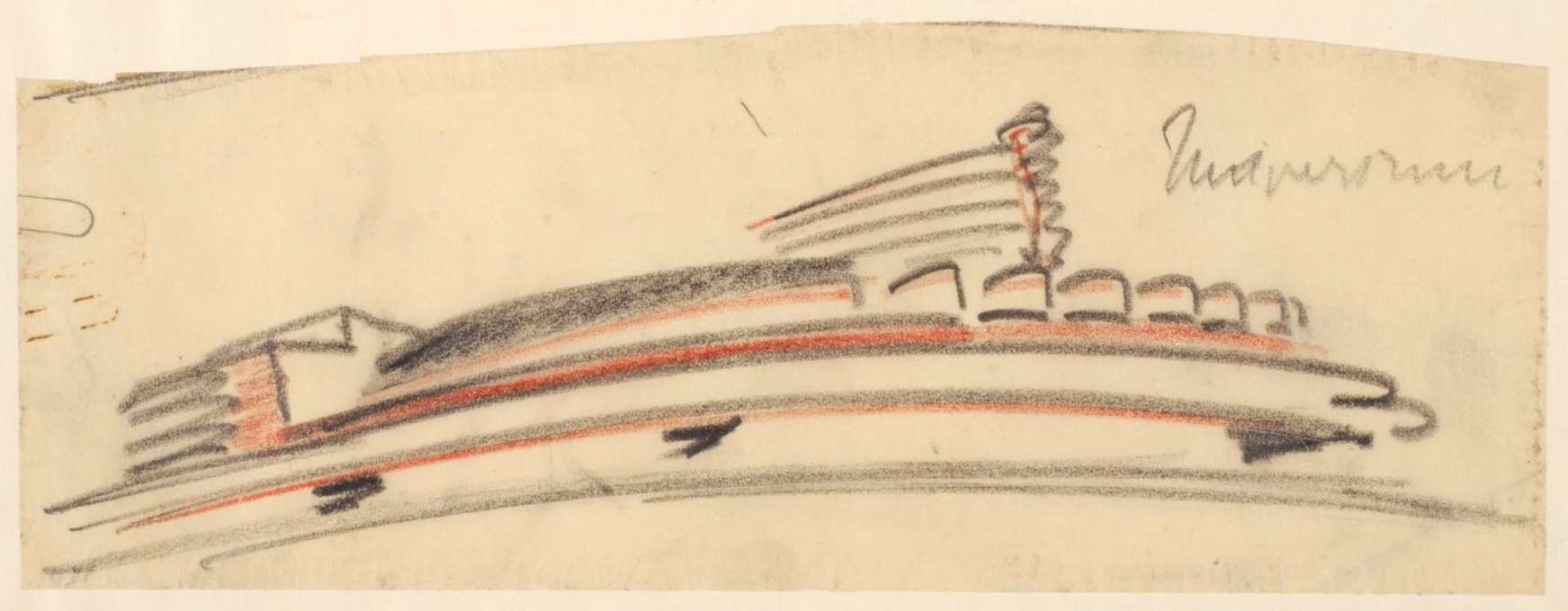

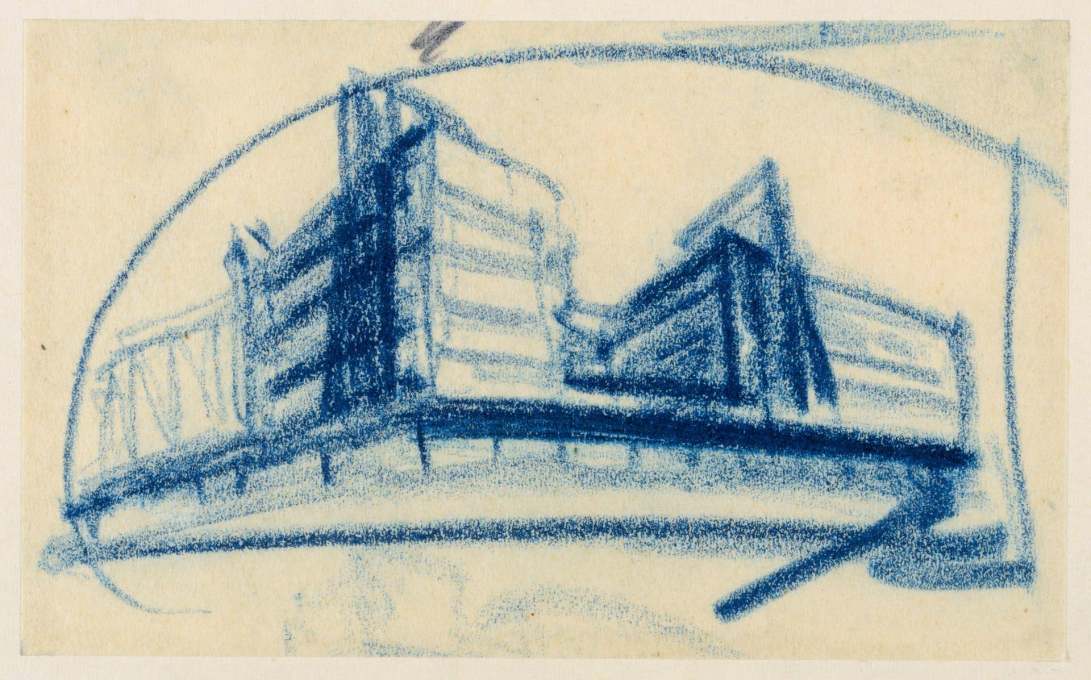

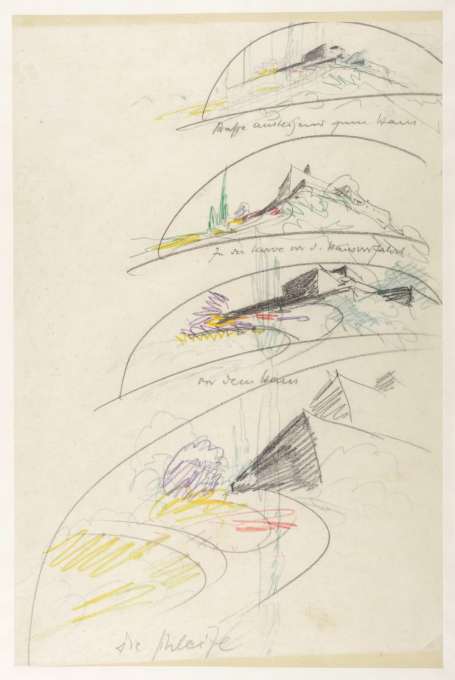

This exhibition communicates this extraordinary energy and breath of his practice – not so much through the representation and analysis of the buildings themselves – which is fairly scant – but through their genesis, in a series of brilliant sketches – which form the basis of a large archive of the architect’s work held by the Kunstbibliotek at the Staatliche Museum in Berlin. These quick expressive drawings, often distinctive worms-eye views, show the phenomenal productivity of his imagination.

Many sheets of paper are covered with three or four rapid re-workings of one idea, of the massing of a building, their breathless, urgency still evident. This was a man in a hurry.

Luckily so in retrospective. As the most prominent German-Jewish architect, his career in Germany was cut short by the coming to power of the Nazis in 1933 – yet his enormous output in the 1920s meant he had already produced a body of work that many only accumulate over a long career.

He emigrated first to England where he successfully restarted his practice in London, moving this later to what was then Palestine and then just before the Second World War, to the United States. That he could successfully juggle so much set-back and change, is perhaps explained by another part of the archival display: the copious and affectionate letters between him and his wife Luise, a celebrated cellist, which indicates the stability of the happy home life he enjoyed, despite its peripatetic nature – the latter underlined by these letters often written on hotel notepaper from across Europe and the US.

Of course his very energy and eclecticism of his work – flirting with expressionism, constructivism , moderne-luxe, and white box high modernism – can at times seem to undermine the importance of the work. He had such ease and facility in design that the heart of the work sometimes seems to be missing, and he left no polemical architectural tracts to help fill in the blanks. His projects were never as spatially inventive internally as Corb or Mies, their effect more concentrated on the outside – in the graphic photogenic shapes of their façades. Yet as such, they are perhaps far more relevant and prescient of so much contemporary work and practice today: an architecture of form and image.

However unlike the dead CGI’s with which today’s architects try to communicate their visions, these visualisations of his buildings in his sketches are themselves touching on genius.

– Rob Wilson, uncube, Berlin

3 Continents - 7 Countries.

Works by Erich Mendelsohn from the Kunstbibliothek's Architecture Collection

until January 26, 2014

Kunstbibliothek

Staatliche Museen zu Berlin

Matthäikirchplatz

10785 Berlin