In 1982, the young architect Iain Low escaped apartheid in South Africa – with its problematic diet of State-commissioned architectural work: from military bases to segregated police stations – to live in Lesotho and over five years developed a school-building programme that enshrined the principles of self-reliance. Hannah Le Roux looks back at his work and sees a model still relevant today.

Maseru is the capital of Lesotho, an independent constitutional monarchy with a history as a place of refuge in the heart of Southern Africa. On the edge of the ever-spreading town, set between sandstone slopes and grazing land, is the sanctuary of Maseru High School’s library, a carefully-crafted temple to rural learning and job creation, yet also to architectural history. The architect of this unlikely mix is Iain Low, who, as a young South African during the height of apartheid in the early 1980s, confronted by the choices of compulsory military service or exile, found his own moral refuge in Lesotho.

Low designed Maseru High School in 1986 while working for the Training for Self-Reliance Project that constructed schools funded with World Bank loans. Over five years of self-imposed exile, he extended the programme into one in which architecture both represented and enacted self-reliance. Low estimates that two to three hundred schools were built under the programme through the agency of the draftsmen and builders that the project had trained. Lesotho today has one of the continent’s highest literacy rates. The design approach that Low brought to the Schools project owed some debt to the structuralist thinking of the 1970s, whilst their social agenda anticipates contemporary humanitarian studios and awards for architecture in development.

The construction system engages with ways of making that enable transitions between the colonial, old vernaculars and modern construction. As a scalar, modular system, it enabled replication by draftsmen who could adapt it to different topographies and builders. The concrete block piers were designed to accommodate either stone, site-constructed concrete blocks or clay bricks as infill – whatever was most accessible on site. Equally lucid is the use of straightforward simple technologies: clear sheeting for daylighting, trombe walls for passive solar heating, cross-ventilation and rainwater harvesting. But even without drawings, the School system went viral as builders have transferred the technology to other schools and houses.

The other quality of the schools is their neo-classical detailing and urban siting. The relationship between Latin culture and learning this evokes isn’t incidental: Lesotho has a long mission tradition, and its university town is named Roma. Both as individual buildings and in larger complexes, such as the cluster of classrooms, support pavilions, church and housing at Qoaling, the schools work as catalytic urban interventions, laid out with careful consideration of external spaces as places of movement and gathering. The proportioning and careful siting of the Maseru library, likewise evoke a classical authority, scaled to meet its African context.

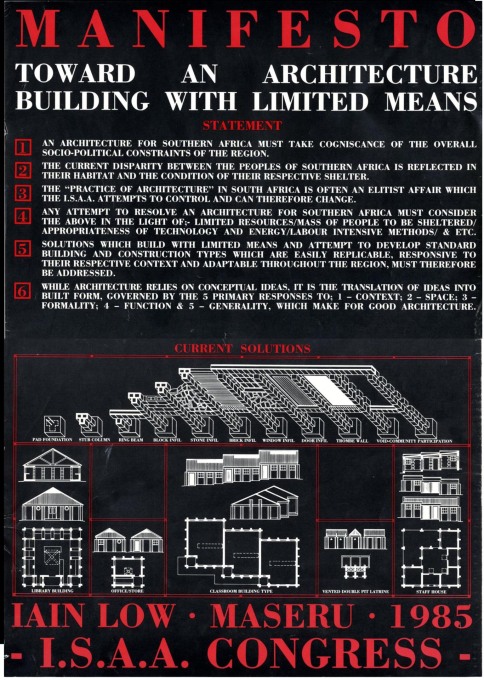

The commitment to combining both visual and material intentions in a system for rural schools is remarkable. It comes in part from the limited time and spatial scales of the project, as well as from the intense focus that comes of work in exile. But it also has the quality of a political counter-project, one that kept an eye on the situation over the border to South Africa, where apartheid was still, literally, being constructed, in the form of schools for black children that were poor mirrors of those given to whites. In a 1985 manifesto illustrated with his “current solutions”, Low wrote: “the ‘practice of architecture’ in South Africa is often an elitist affair which the Institute of South African Architects attempts to control and can therefore change”. In part he was alluding to that Institute’s actions in censoring its own members who had spoken out against accepting commissions for State work, condemning yet more architects to self-exile.

Instead of reflecting on this model for addressing the priorities of a developing country, however, many other South African professionals continued to invest their skills in the last and most insane phase of apartheid planning for puppet bureaucracies like Bophutatswana, military bases on the borders and intricately segregated police stations. The consequences of their reaction spans thirty years, with everyday structures such as schools mostly built to typologies dating from the 1970s. It is not so much the lack of design as the lack of a social agenda for design that sets South Africa apart from its tiny enclaved neighbour Lesotho. It is tragic that apartheid agendas prevented the the Schools programme from crossing this border.

Still, the viral qualities of ideas do spread. In the face of the Institute’s indifference in the 1980s, Iain Low was hosted by students at congresses that presented alternative practices for a post-apartheid world that they, at least, believed was imminent. In this way, the Universities reinstated their position in hosting oppositional thinking, much as the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg had notably done in the 1930s and again in the 1970s.

Yet it is unclear when Africa will create conditions that are ripe for the rolling out at scale of the idealist visions of architects like Low, as well as those who preceded and follow him. However the tone of some emerging studios and their projects in Africa, such as buildcollective, [a]FA, PITCHAfrica and 1:1 – Agency of Engagement resonates with Low’s, an optimism that is necessary and will, probably, be tempered in time. For now, they deserve the recognition for continuing a thread of practice and construction that links ideas and projects, exiles and remote communities.

– Hannah Le Roux teaches, practices, curates and writes about architecture, and is a senior lecturer at the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg. Her current research, “lived modernism”, is based on the observation of change over time in modernist spaces, and the design practices that catalyse the social appropriation of space.