Chris Luth’s new documentary investigates urban transformation in Turkey, a practice that triggered mass demonstrations across the country last summer. In the midst of these demonstrations, he and his team were invited to show the film in China. Luth explains here how the Chinese responded to the film’s critical portrayal of sometimes-oppressive state-led planning.

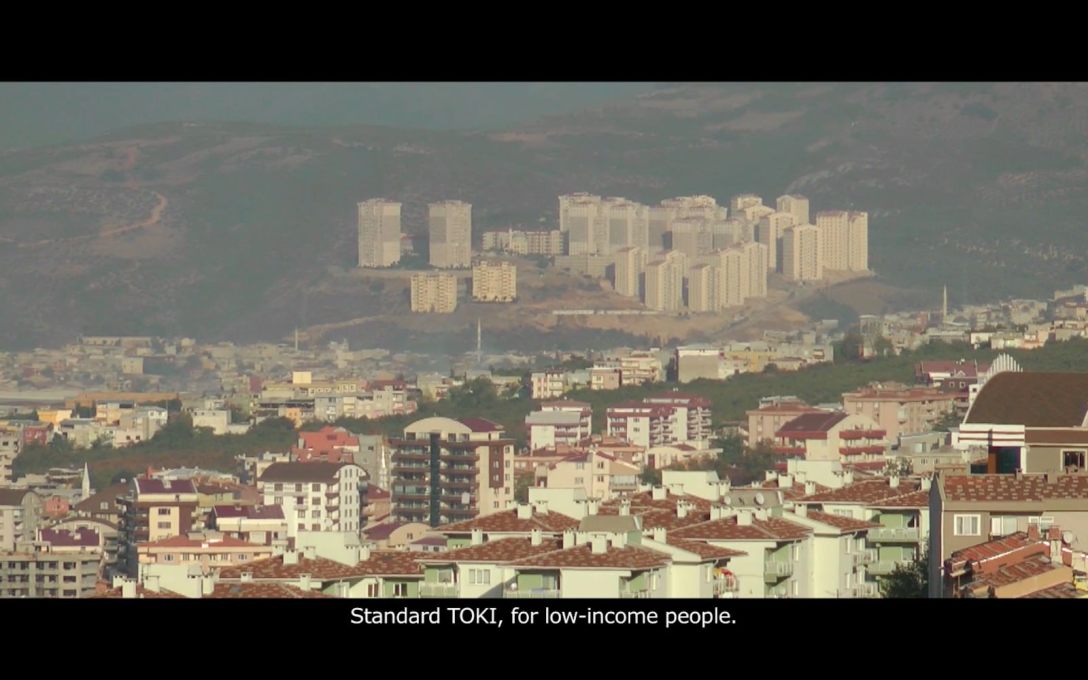

AGORAPHOBIA – Investigating Turkey’s Urban Transformation is a road movie. It follows an international group of architects and planners as they travel from Ankara via Bursa to Istanbul. During site visits and meetings with residents and authorities, they discuss the generic apartment towers that are being erected throughout the country with little regard for people and place. In an extreme case, evicted inhabitants refuse to move into the soulless towers that have replaced their centuries-old neighbourhood, appalled by the lack of quality and high mortgages.

Turkish citizens often prefer to live in gecekondu, houses that are literally built overnight. Instant inhabitation secures them from demolition without legal proceedings. Most of such neighbourhoods were created at city’s peripheries during the massive urbanisation wave of 1950-1980. The American journalist Robert Neuwirth estimates that half of Istanbul’s inhabitants live in the city’s gecekondu, and many more live in similar settlements across the country.

The state-owned Housing Development Administration of Turkey (TOKI) is urban transformation’s major instigator. When confronted with forced evictions and the lack of quality of its designs, the authorities invariably say they are “in a hurry”. Why they are so hurried remains unclear, as rural to urban migration is well over its peak. But in spite of poor planning results, this rush is likely to increase. A new law makes an astonishing 6.5 million buildings eligible for immediate transformation, legitimated by the risk of earthquakes. Aptly nicknamed the Disaster Law, critics fear it will mainly serve the construction industry, a pillar of the Turkish economy.

“This film could have been made in China!” responded a shocked Chinese architect who we had invited for a post-screening discussion. He recognises the rush and evictions. Unlike Turkey, China is still in the midst of a massive rural to urban migration wave, with hundreds of millions of peasants flocking to the cities. Due to the hukou household registration system, newcomers have limited citizen rights and many become part of the floating population that move from city to city looking for work and cheap housing. Different circumstances have led to a similarly pressing situation as in Turkey.

Shenzhen is one of the cities our film is screened in. It is probably the world’s most extreme example of rapid urbanisation. When it became China’s first Special Economic Zone in 1979, it was little more than a village of farmers and fishermen. Aided by massive foreign investment, it has grown into a metropolis of a staggering 11 million residents (some estimates go up to 14 million) and still remains one of the world’s fastest growing cities. Its unimaginable patchwork of urban fabrics is seamed by highways and lined with skyscrapers. Tiny low-rise buildings along winding alleys and squashed matrixes of mid-rise apartment blocks, often only a metre apart, form examples of the unique Chinese phenomenon of the “urban village”.

Unlike the gecekondu, which were built at the periphery of existing cities, these villages existed prior to the city. Farmland was easier to build on (no inhabitants needed to be evicted) and the villages became lively pockets of informality in-between rapidly urbanising farmland. As the pressure on the land increased many villages were redeveloped, creating densities unimagined by building codes. This was highly lucrative for the original inhabitants who let the additional floor space to the ever-growing influx of rural migrants in search of low rents. Still communally owned, urban villages are often well organised. Many have guarded entrances and collect toll from drivers as an additional source of revenue.

In spite of their informal status and the fact that China remains a communist country, the owners have well-protected property rights. And because they increased densities so dramatically, none can afford the financial compensation for evicting them – quite the opposite from the fragile position of the gecekondu landlords. Property rights are in fact so well protected that heritage preservation becomes problematic, especially in Beijing’s ancient hutong alleyway houses that continue to be demolished and replaced by new high-rise constructions. Lured by big profits, many favour selling out over preserving their way of life and architectural heritage.

When invited to China, we worried about the freedom people would have to freely discuss urban policies. The refusal of one of our translators to translate critical remarks seemed to justify our concerns. As a well-known Chinese architect told us, “We have a different kind of democracy”, referring to China’s one-party system and a culture that values community over the individual. The second unique Chinese phenomenon of the nail house shows what may happen to those who challenge this hierarchy. Owners who refuse to sell their property may find it standing solitary amidst on-going demolition and construction.

At closer inspection, the nail houses are more than just heroic struggles of solitary activists against the system. Backed by a new law that obliges developers to reach an agreement with owners prior to demolition, these individuals have a very strong negotiating position against the mighty construction industry – different kind of democracy or not.

–Chris Luth is an independent architect and curator based in Rotterdam. He is executive producer of AGORAPHOBIA – Investigating Turkey’s Urban Transformation.

The screening of AGORAPHOBIA at the Shenzhen Bi-City Biennale of Urbanism\Architecture was financially supported by the Creative Industries Fund NL. It was also screened at Studio-X Beijing, the University of Hong Kong / Shanghai Study Centre, EMGdotART in Guangzhou, the Hong Kong Bi-City Biennale of Urbanism\Architecture and the University of Saint Joseph in Macau. All screenings were organised in collaboration with Merve Bedir of L+CC, who co-produced the film.