While putting together our Space issue No. 19, it became undeniably clear how many of today's outlandish (out-Earth-ish) spacey technologies stem directly from science fiction. Interfaces, spaceships, weapons, space suits, and of course, space architecture – books and movies precede, predict, and even restrict the way actual science, technology and design evolve. We asked Claire L. Evans to expound on the reciprocal relationship between what we imagine and what we get.

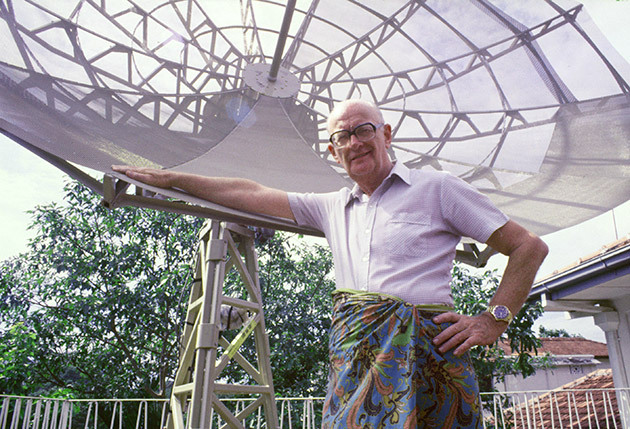

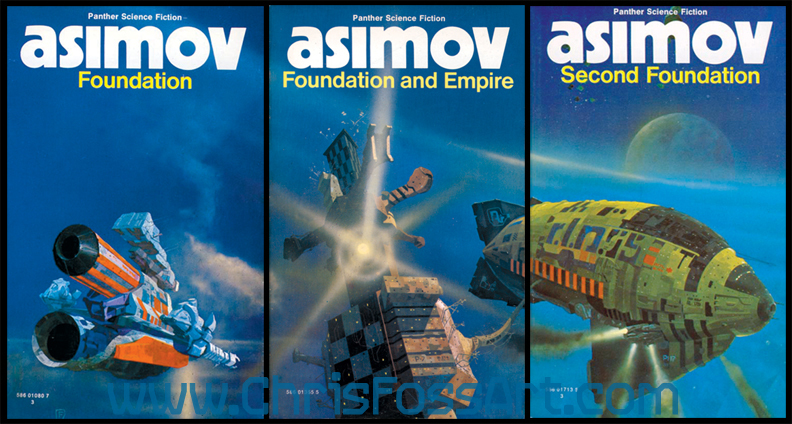

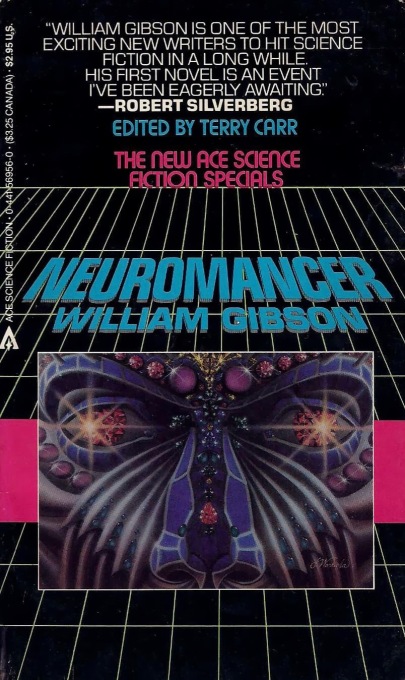

Those who try to legitimise science fiction often invoke its prophecies. It’s worth pointing out that science-fiction writer Arthur C. Clarke proposed the geostationary orbit for communications satellites, for example, or that Karel Capek coined the term “robot” and William Gibson, the eminence grise of cyberpunk, presaged cyberspace as a “collective hallucination experienced daily by billions of legitimate operators”.

Although no literature should be judged by the strength of its predictions, science fiction’s influence in design is diverse. Take the Taser: an electroshock weapon whose name is an acronym for “Thomas A. Swift’s Electric Rifle.” This is a nod to the turn-of-the-century Tom Swift series of juvenile science fiction books, which imagined (among other boyish things) a gun firing bolts of electricity. Or take Motorola’s iconic StarTAC flip-phone, with its suspicious resemblance to a Star Trek communicator.

Did Jack Cover, the inventor of the Taser, get the idea from his childhood reading, or did the Tom Swift novels somehow conjure the technology into being? Did we carry around flip-phones in the 1990s because hardware designers grew up watching Star Trek, or did Gene Rodenberry and his team of writers and production designers predict the future? We might do well to heed Isaac Asimov’s observation that “science-fiction writers and readers didn’t put a man on the Moon all by themselves, but they created a climate in which the goal of putting a man on the Moon became acceptable”.

It’s what Douglas R. Hofstadter calls a “tangled hierarchy”. Jack Cover did love Tom Swift novels, but he designed the Taser after reading about a man who became immobilised by a high-voltage fence while hiking. And Motorola, as it turns out, engineered the flip-up phone after the public responded negatively to a previous flip-down version – whether from cultural osmosis or specific Trek fandom, people simply expected a flip-phone to work like it did in the movies. Science fiction may imagine the future, after all, but it’s designers who implement it.

This doesn’t always call for a decades-long lag between literary prediction and fact. For example, a scientist named John Underkoffler, who had already built similar systems at MIT, designed the immersive tactile computer interfaces of the 2002 film Minority Report. After gauging audience response to the interface – “they felt like they’d seen something that either was real or should be” – he told me in 2008, Underkoffler founded Oblong Industries, a company that now sells commercial versions of the Minority Report computers, networked, gestural computing environments immediately recognisable from their star turn in science fiction.

Oblong Industries is a leader in futuristic motion-sensor technology such as g-speak™, addressing real-time big-data challenges in applications such as military simulation and energy grid management. “Minority Report”, anyone? (Video courtesy Oblong Industries)

Minority Report’s action takes place in 2054, but its interface already existed at the MIT Media Lab in 2002. If it looked futuristic to audiences, it’s because most weren’t familiar with the current state of gestural computing. It took science fiction’s unique capacity to meld human desires with technological speculation to place them in the realm of commercial possibility. Is this prediction per se, or did science fiction just yank the leash and bring the future to heel?

A successful piece of science fiction allows readers to become comfortable with the future – with how it looks, as in Minority Report’s orchestra of screens, or how it feels, as in Neuromancer’s intoxicating connectivity – before it becomes the present, and then the past. It softens the edge of tomorrow bearing inexorably upon us. As a genre consumed by a mass audience, it informs the very world it critiques, ushering in a future inseparable from our imaginations of it. If that seems like an unnecessarily reflexive reading, that’s because science fiction is an ouroboros, a snake forever eating its own tail.

– Claire L. Evans is a writer and artist working in Los Angeles. Her “day job” is as the singer and co-author of the conceptual disco-pop band YACHT. A science journalist and science-fiction critic, she is a regular contributor to Aeon Magazine, Vice, Motherboard, and Grantland, and is the editor-at-large of OMNI Reboot. A collected book of her essays, High Frontiers, is now available from Publication Studio. www.clairelevans.com