There has been recent media obsession with the decayed structures of the 20th century, particularly post-Soviet or post-capitalist remnants: the empty hulks of brutalist Black Sea resorts or the abandoned Piranesian behemoths of Detroit. This renewed interest in broken buildings is reflected in the current exhibition Ruin Lust at Tate Britain, which focusses on artists responses to ruined structures, from romantic nineteenth century capriccios, to visions of war, and more contemporary work of film and assemblage, drawing on the Tate’s own collections. Mark Irving visited and wondered if the exhibition misses out on the bigger picture.

It’s much easier to study the ruins of buildings than face the physical ruin of people. So there is something aseptic about Ruin Lust, an exhibition that brings together paintings, engravings, drawings, photographs, sculptures, and film to create a curatorial but bloodless romance with decaying man-made structures. Ruins as artistic subject rather than as reportage offer an aesthetic feast – so many perforated walls, filigree arches, the allure of absence, the ease of fickle memories – but at the cost of any personal truth. Little here is felt as an individual’s loss, and this is why ruins without the presence of people so easily serve as lightning rods for a sentimentalism that, under its elegant skin, is inevitably cold and without charity.

The Picturesque – that staging of graceful ruination best viewed from the vantage point of a tea pavilion or carefully escorted walk – is partially to blame. Here J.M.W.Turner’s watercolour studies of Tintern Abbey offer silvery visions of decay-as-delight, with orphaned gothic arches given renewed sacral potency by his airy brush. John Sell Cotman’s exquisitely balanced watercolour of The Doorway of the Refectory, Rievaulx Abbey of 1803 has a cloacal quality – the darkened doorway itself becoming a sucking maw, absorbing the viewer with its needy nostalgia. Gandy’s ruined view of Soane’s Bank of England and Gustave Doré’s The New Zealander – an engraved vision of a ruined London visited by the eponymous empire edge-dweller – read less as warnings of inevitable decline than as onanistic prompts for ruinophiliacs. The most spectacularly vulgar image on display is John Martin’s epic painting – once ruined itself following a flood at the Tate Gallery in 1928 – of the destruction of Pompeii and Herculaneum. He pimps perdition like no other artist.

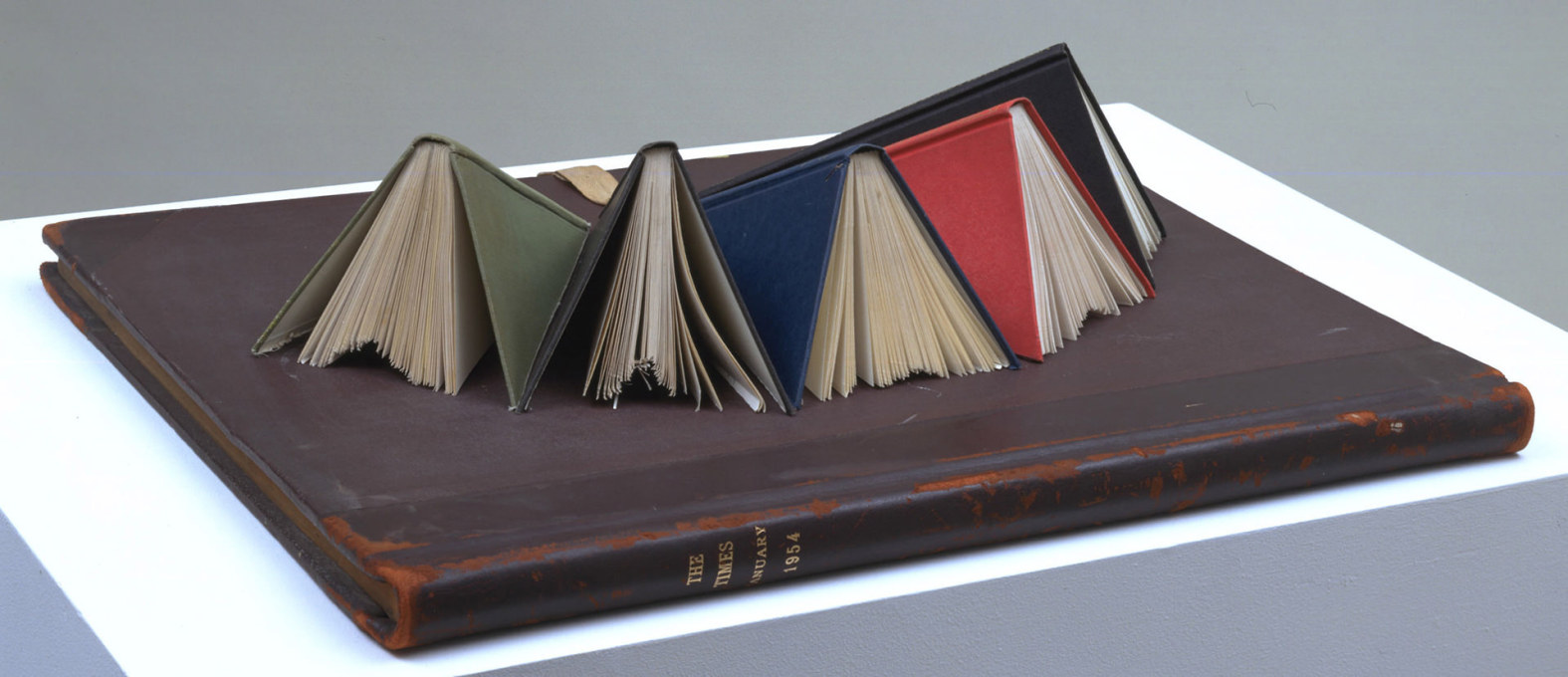

John Piper, Paul Nash and other mid-century British artists feature, but without flair. Graham Sutherland’s Burnt Paper Warehouse of 1941, resembling a seventeenth-century still life in its tonal concentration, is a welcome addition. A discovery is David McFall’s Bull Calf of 1942, fashioned with great delicacy and firmness of line out of the ruined capital found after a bombing raid: it has the classical majesty of a Poussin and the sensuality of a Sumerian animal-god. John Latham – whose work only seems to get better the more you see it – is represented by an installation from 1976: Five Sisters Bing, consisting of five small books spliced into a larger one. It’s a brilliant abstraction of the slag heaps at the Westwood Shale-oil Works. Laura Oldfield Ford, born 1973, is a star: she manages to turn an apparent insouciance in her choice of media – ballpoint pen, scrawled neon marker – into thoughtful essays on the decrepitude of mid-century modernist ideals through her dazzling drawing.

A less successful inclusion is Tacita Dean’s film Kodak, 2006, a meditation on the demise of 16mm film as a medium. Its Byzantine, jeweled darkness is striking, but the curators have failed to contextualise convincingly this piece’s inclusion in the exhibition. Another moving-image based work, Gerard Byrne’s television installation 1984 and Beyond, 2005–7 –reimagines a past future based on a 1963 Playboy interview with science fiction writers – including Isaac Asimov, Ray Bradbury and Arthur C. Clarke – speculating on the world of 1984. This fails to inspire because it feels a mere exercise in retro-fashion: furthermore, its dreary experiential format – inviting visitors to watch television screens while wearing headphones - means it is unable to hold the gallery space in the way that Dean’s work undoubtedly does. Jane and Louise Wilson’s enormous black and white photographic prints possess the space greedily, but with reason: their skill lies in their framing of the subject – giant concrete coastal wartime bunkers rendered titanic in scale and set against the bleached whiteness of a constrained sky.

Structure, deconstruction – the continuing obsession of the clever ape: the greater ruin – the twisting effects of our presence on the planet – remains the more urgent background to, but seemingly beyond the curatorial grasp of, this rather passionless exhibition. This is due to these artworks’ inevitable fixation on the ruin as artefact – the object within a landscape rather than the landscape itself. Inevitable, because art cannot separate itself from a system of value-making that treats objects as commodities operating within a market. This is why this age-old lust for possessing objects finds the ruin – a condition in which the structural integrity of the artefact is compromised and becomes a nostalgic echo of its past self – such compulsive viewing. But beyond the ruin-as-sentiment lies a greater disintegration, a systemic ecological ruination – gradual, episodic, but potentially cataclysmic – of the infrastructure of life. To represent this panoramic understanding you don’t need an exhibition. You may not even need Art itself.

– Mark Irving is a content developer and story designer based in London. Founder and principal at Visible Impression Ltd, he connects users to content and people to places.

Ruin Lust

March 4 to May 18, 2014

Tate Britain

Millbank

London SW1P 4RG