Rounding out our month of Urban Commons, we move from centre to periphery: the Italian city of Matera. One of Europe’s earliest human settlements, today Matera’s population of 60,000 faces similar challenges to other mid-sized towns and cities across the continent – from vast disused spaces to unemployment to “brain drain”. A new initiative called unMonastery has set up camp there with the hopes of tackling these issues. Elvia Wilk talks to one of the project’s initiators, Ben Vickers, to find out why Benedictine principles of the commons could be used to underpin today’s open-source movement.

--

The unMonastery has a rather complex lineage, drawing from a variety of theoretical models, private initiatives, and public organisations. How did it evolve?

On the surface, the unMonastery’s format could cause some cognitive dissonance, as the project appears highly institutionally backed while retaining an anarchic edge. Yet these sorts of contradictions make sense in the context of its birthplace. In 2012 the Council of Europe’s Social Cohesion Research and Early Warning Division (the philosophers’ quarters of the European Union) wanted to produce a policy report on youth transition in times of crisis. What they created was EdgeRyders, a “distributed think tank” or online forum aiming to collectively produce a report by leveraging the collective intelligence of its participants.

What did that think tank do?

EdgeRyders first came together physically at 2012 Living on the Edge conference in Strasbourg at the Council of Europe, where around 250 activists, social innovators, hackers, policy makers, squatters, artists, and others gathered in the CoE’s plenary to debate with policy makers. This was a really weird happening: it was the first time I’d personally witnessed some of the most provocative activists and individuals interacting with power. It was also the first time I’d seen those in the halls of power have to deal with a twitter feed rolling at the rate of a tweet-per-second in the background of their keynotes.

It wasn’t until the unConference – a sort of cognitive hackathon – in the following days that the idea for the unMonastery was spawned, in a session of around 20 individuals wanting to find ways to support projects that don’t tick any convenient funding boxes. EdgeRyders then became autonomous from its institutional roots, and in a three-day Brussels conference later that year we designed the core of the unMonastery model, built a website, launched a call for applicants and designed its visual identity. From the beginning it’s been about seeking an understanding of how a network can interact with power. We aren’t interested in isolationist politics when it comes to getting something done.

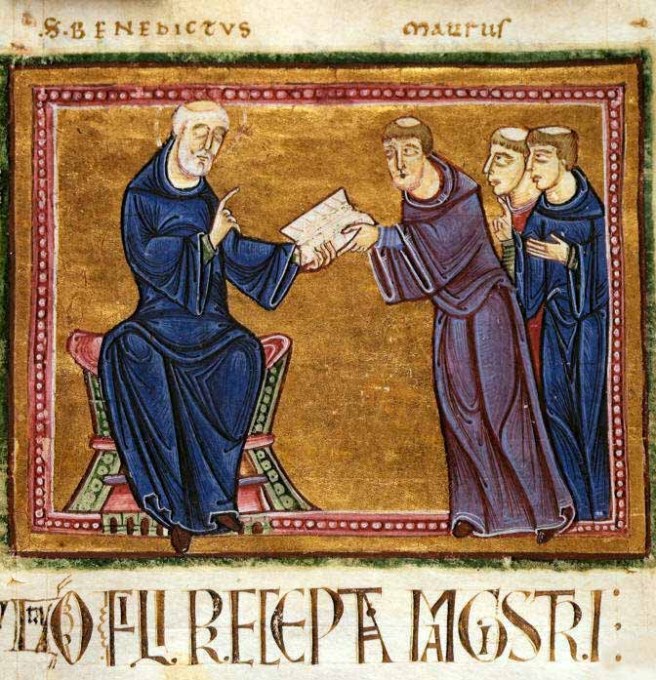

Which aspects of monastic life directly inspired the initiative, and which ones make up the “un”?

At a basic level the historical role of the monastery in Europe involved a range of features we want to reproduce, including our use of a physical place – a building or set of buildings – the members’ commitment to a particular way of being within their home, and the drive to help or serve an existing community. Features that we’ve avoided reproducing are aspects such as a strict hierarchy, male only participation, and fixed religious ideology.

But our provocations for mining the metaphor of the monastery are much deeper than these formal aspects. There is a sense that something within the social order has gone fundamentally awry in the way we currently organise society. Theorist Michel Bauwen summarises this sentiment in his recent letter to Pope Francis, as does philosopher Giorgio Agamben in his newest book The Highest Poverty. In response, it’s clear to us that we can learn a lot about establishing long-term change from the Benedictine Rule, particularly when we reframe it as more a protocol or “software” than rulebook. unMonasterian Alberto Cottica lucidly extrapolates upon our reasoning on his blog.

What makes Matera an ideal site for this project?

We didn’t anticipate that Matera would be the first site. Many different locations were proposed, but it was only in Matera that the idea was seriously backed, as part of the city’s bid for Capital of Culture in 2019. With that said, it now seems like destiny: Matera is like nowhere else on earth. The weight of history matters here. Matera has been around since the Palaeolithic era, one of the earliest human settlements in Europe. Benedictine and Basilian monastic institutions colonised and helped build the city – we literally stand on the shoulders of giants, which ensures some modesty in our endeavour. That said, the city also has a unique set of problems in respect to its status as a tourist centre since being ordained a UNESCO world heritage site in 1993.

The unMonastery tackles three major challenges in the community: high rates of unemployment, vast amounts of unused space, and reduction of public services due to the economic crisis. Do you employ a three-pronged approach to deal with these?

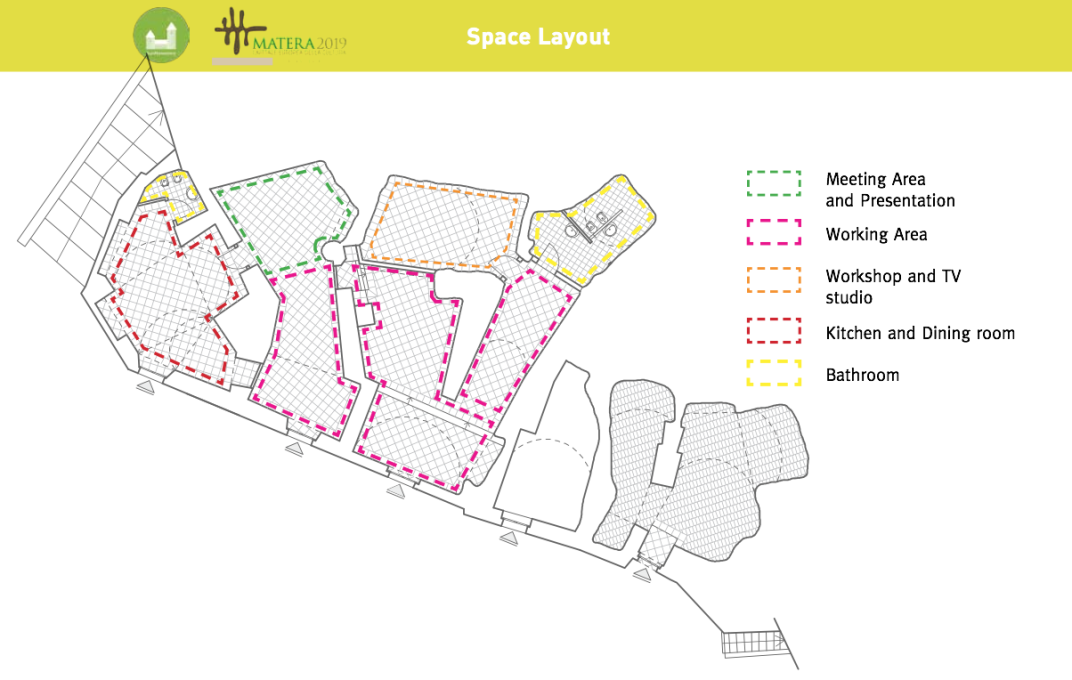

These three challenges were set out to clearly communicate with policy makers and expand the applicability of the model to a set of global issues. Our way of addressing them broadly is to re-open a disused space for the intentionally and unintentionally unemployed youth of the world, allowing them to do work they care about. Yet of course we face specific challenges in a given locality. Here, the plans were established through a series of workshops with citizens in Matera a year before the project opened its doors, in which we identified 43 challenges of varying scale. These were whittled down to 12 that we felt were feasible for a four-month prototype. We then launched an international call for applications. Given the demands of the position, sometimes I’m surprised that anyone applied!

Is it really possible to stem the flow of the young towards major cities?

I don’t know the answer to this, or at least not yet. The unMonastery is an experiment: we’re building a prototype to see if it works – it might not. Our model isn’t designed to depopulate the cities of the world of their bright young minds, it’s designed to create an alternative space. We don’t believe that cities should be abandoned, but we should question their utility for the world that we want to live in over the next century. Recently we’ve begun working on a different city model, a sort of embassy for an emergent, itinerant network: unEmbassy.

Sometimes the unMonastery is humorously described as “like a commune but with the internet.” Part of the failing of the communes was their lack of diversity, the calcification of power structures and deeply internalised groupthink as a result of their back-to-the-land remoteness. The unMonastery consciously and cautiously draws on this tradition but with the sincere hope to learn from the communes’ mistakes.

A project I find relevant for comparison is Atelier Architecture Autogeree’s R-URBAN initiative in Colombes, France (covered in our Urban Commons issue). As opposed to AAA’s focus on implementing urban farming, ecological experiments, and recycling initiatives, you emphasise technological literacy – including mapping systems, open-source solar panels, radio, and wireless networks. Why focus on networked technology to address economic and social issues?

Because it’s what the early initiators of the project live and breathe. That said, we’re not exclusively focused on technological cure-alls and we do have similar plans for urban farming initiatives. It doesn’t matter how many delegative voting systems, crypto-currencies or distributed protocols we build – at some point soon we’re going to have to deal with the hard stuff that clever apps can’t solve, like property relations, building roads and health care systems.

We don’t believe that the Smart City has to be a dystopia, but if we don’t act now that’s a very possible outcome. So we look at ways to adapt things that we’ve learnt online that might be applied to a fixed geographical space, such as the tools we’ve built to accelerate software development. Concrete analogous examples are things like GitHub, an online repository for code that allows real-time collaboration and enables anyone to “fork” your code, replicate, modify and adopt it for your own purposes. This approach allows us to consider the issue of leaky “tacit knowledge” that leads to the collapse of a network. When an individual who holds all the knowledge in his or her head leaves or gets hit by a bus, the network forgets everything that person knew.

Almost universally the institutions that shape society suffer from hierarchy as their default organisational form: an anathema to gettings things done in a participatory way. We’re trying to understand if, by working from the perspective the open source technology we’re so familiar with, we can embed the same mechanisms and values in a new form of institution.

There are many ways in which the unMonastery develops a synergy with existing state policy structures. How do you conceive of this relationship between a “sharing economy” and its cooperation – or codependency – with existing economic structures?

Over the centuries, nation-states all over Europe have developed or acquired control of assets, the overarching logic being the support of public services. In recent decades states have found themselves struggling to keep those assets manned, so have had to retreat from many non-core services. Consequently, many such assets – buildings, parks, and even digital assets in the form of data – lie unused, and some are beginning to deteriorate.

To remedy the situation, many public assets have been turned over to the private sector, with mixed results. While there are financial advantages for states, these privatisations have suffered from unintended consequences – for example, the rise of a powerful oligarch caste in Russia in a very short time. In turn, communities have been singled out as candidates to take care of public programmes. In the UK, plans are emerging that could result in up to 500 public libraries being turned over to local communities, together with seed funding.

So the municipality’s move to allow us use of the building in Matera isn’t an isolated event. It’s also significant that Matera’s bid for City of Culture grew from a grassroots initiative that is being orchestrated in a fundamentally different way from other cities, with full community participation. If we want a real decentralisation of control, we will have to find ways to shoulder the burden of work that states have been responsible for. In real terms, this means finding a way to keep the lights on and the toilets flushing.

– Ben Vickers is a curator, writer, network analyst, technologist and luddite. Currently Curator of Digital at the Serpentine Gallery, he co-runs LIMAZULU Project Space, is a NearNow Fellow and facilitates the development of unMonastery, a new civically minded social space based in Matera, Southern Italy.