A new building over which all involved: client, builders, and architects, warmly compliment each other? Surely not! After witnessing a full-on love-in at the press conference for the Hospitalhof in Stuttgart designed by Lederer Ragnarsdóttir Oei Architects, Christian Holl visited the building to judge for himself.

Compliments flew at the press conference for the new Hospitalhof building in Stuttgart, the Protestant Church’s main education institute in the city, and the latest building by Lederer Ragnarsdóttir Oei Architects, whose Ravensburg Art Museum won last year’s German Architecture Prize. Stuttgart’s superintendent, Søren Scheswig, described his pleasure in a building he’s already developed an emotional attachment to, whilst the project manager spoke in satisfaction of how it was finished on time and under budget. Meanwhile one of the practice principals, Jorrún Ragnasdottir, complimented the client on being one of the best that they’d ever had. So satisfaction all round it seems but how does the building stack up in the flesh?

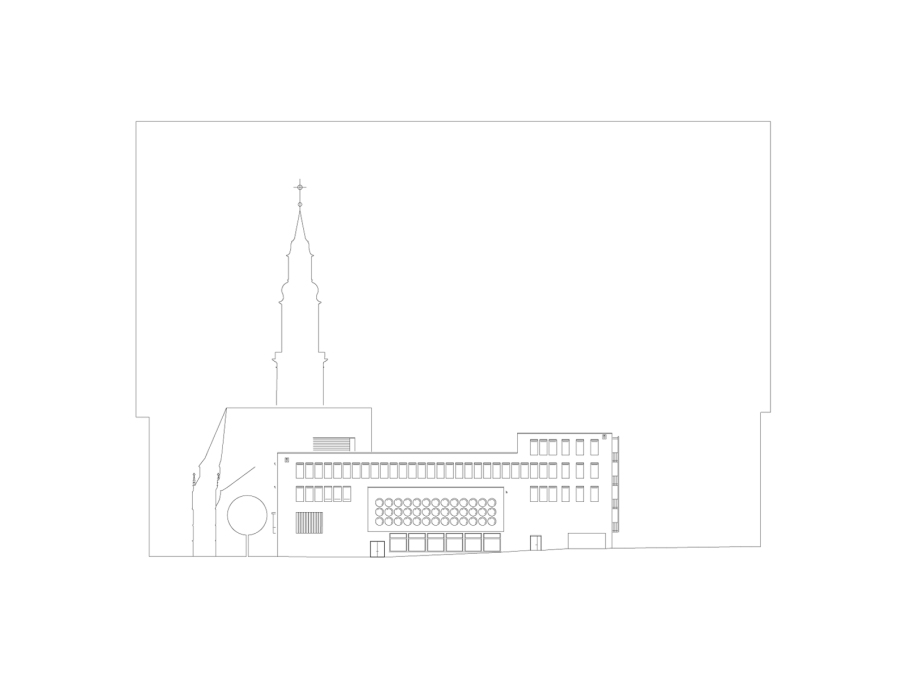

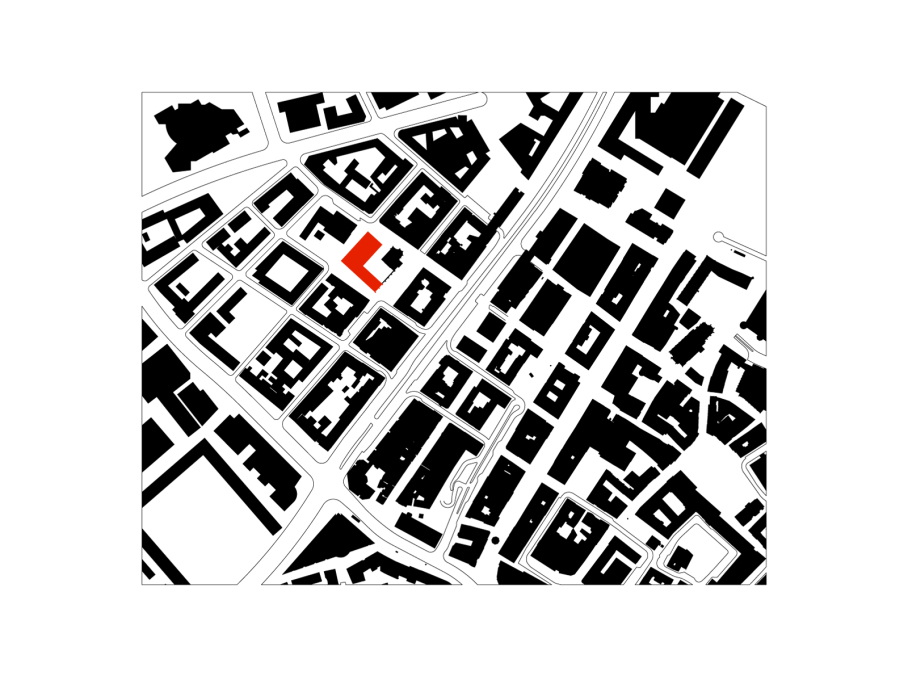

The Hospitalhof was founded as a monastery in the 15th century, and was later used as a hospital, lending its name to both the main church and its surrounding district, Hospitalviertel, an area which still appears to be a blind spot in the city, situated as it is between several major roads. After Second World War air raids which destroyed both the church and the surrounding district, only the church’s chancel was reconstructed, leaving the southern wall of the nave a ruin. Overall the area, despite some improvements, is still waiting for an effective urban planning concept to awaken its potential. The construction of the new Hospitalhof is a major step forward in this: both through its integration with the public realm and as a new centre of activity for the area.

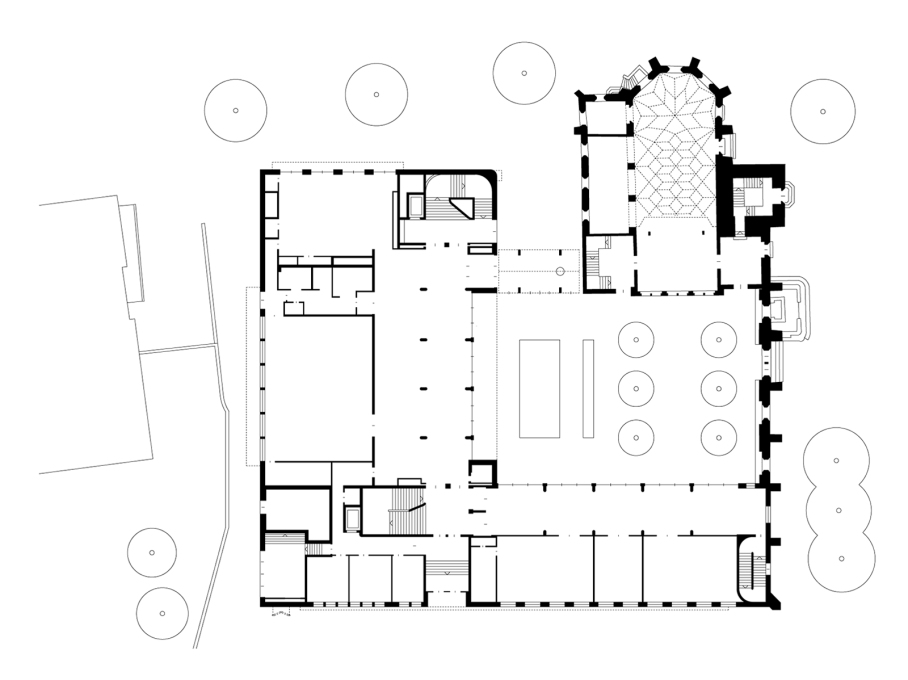

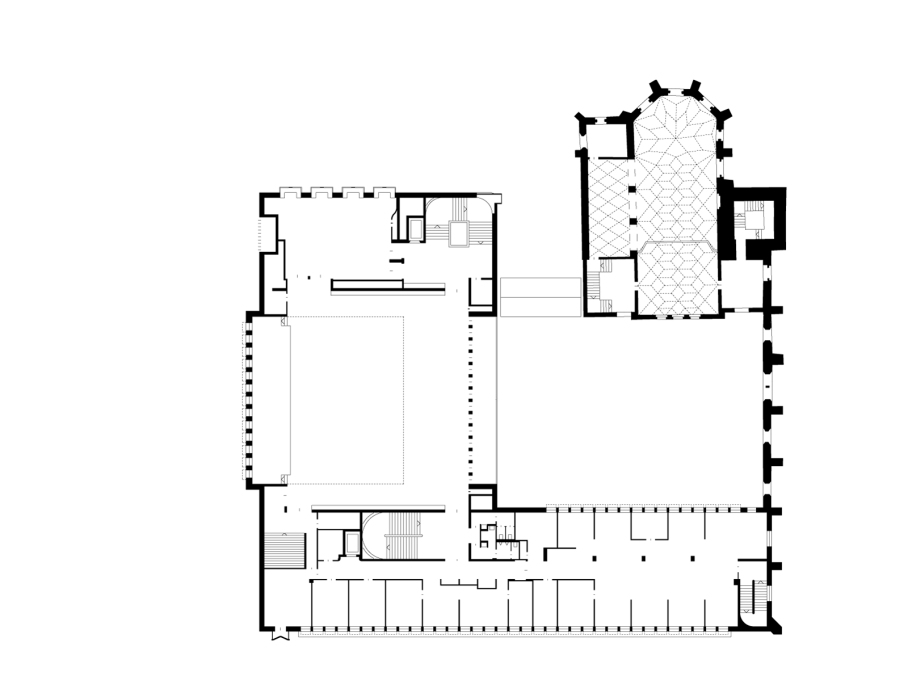

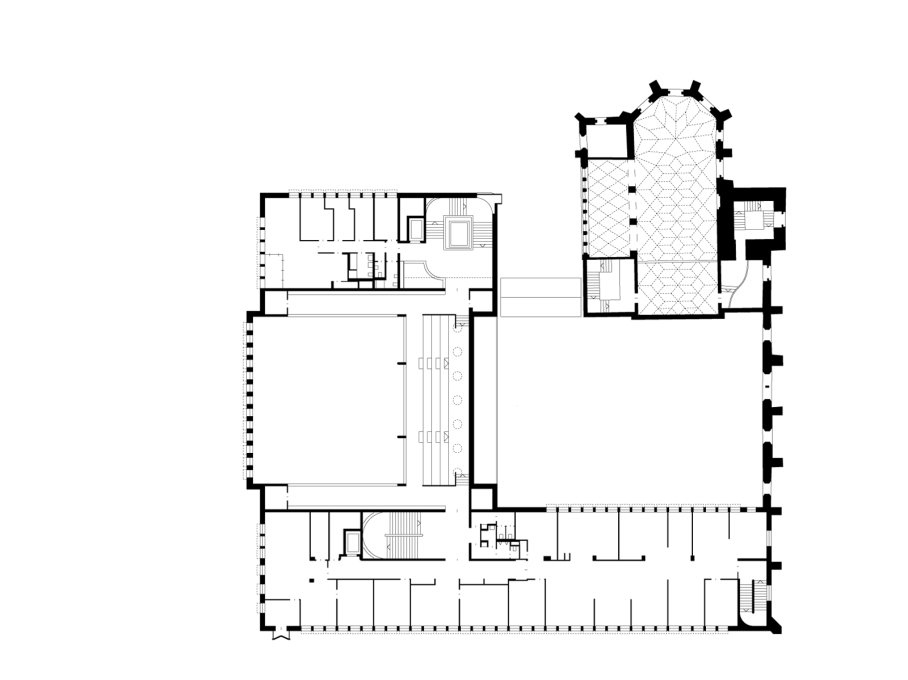

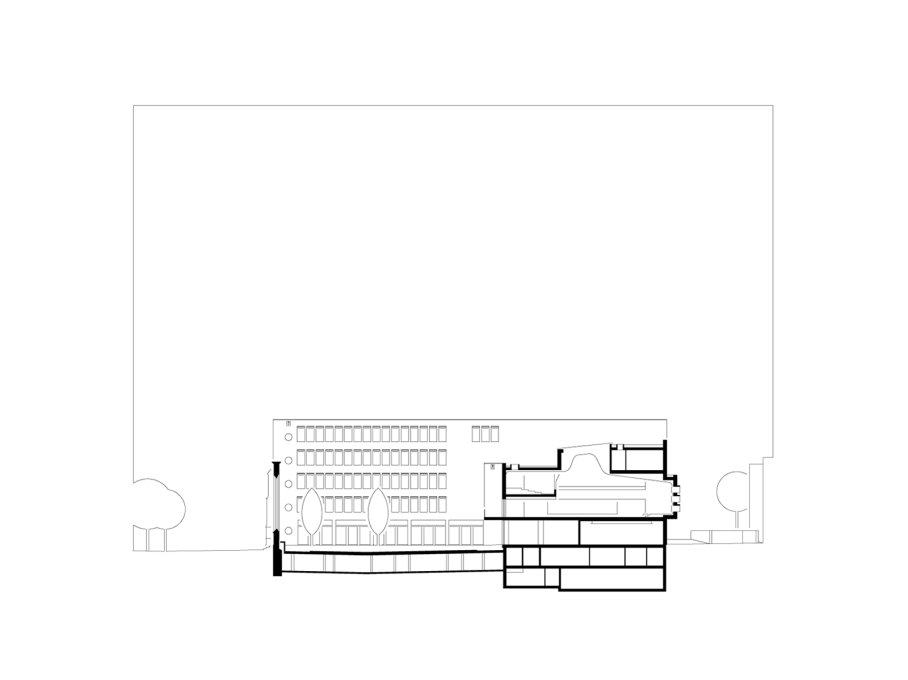

The previous Hospitalhof education centre, designed by Wolf Irion, consisted of an administration building and separate auditorium. Completed in 1961, it was no longer technically up to scratch and physically in a bad condition. Nevertheless the project brief of what was intended as the first phase of a two-phase competition, only specified that the auditorium be refurbished initially, keeping the old administration building in the meantime, to be redeveloped in a second phase. LRO however went the whole hog and proposed demolishing the entire postwar complex in one go and building a completely new Hospitalhof. This enabled them to resolve the awkward separation between the two parts and to construct a single coherent building, that fits all the requirements at once, and in particular improves inner organisation: with seminar and conference rooms situated at the ground level around an L-shaped foyer. Their proposal convinced both the competition jury and the client. Still, for a firm architects not known for having too much respect for postwar architecture, it clearly wasn’t so much of a struggle to propose complete demolition! However in this case, it seems, the results have justified the decision to do so.

The new complex readopts the historic pattern of the old monastery complex. Thus the new administration wing is attached to the nave’s remaining wall, completing it again, with new brickwork in a light grey marking where part of it was previously cut into by the former administration building. Six trees have been planted in the courtyard, which indicate the position of the columns of the original church nave, showing how the architects subtly reference history, and the prewar-form of the building.

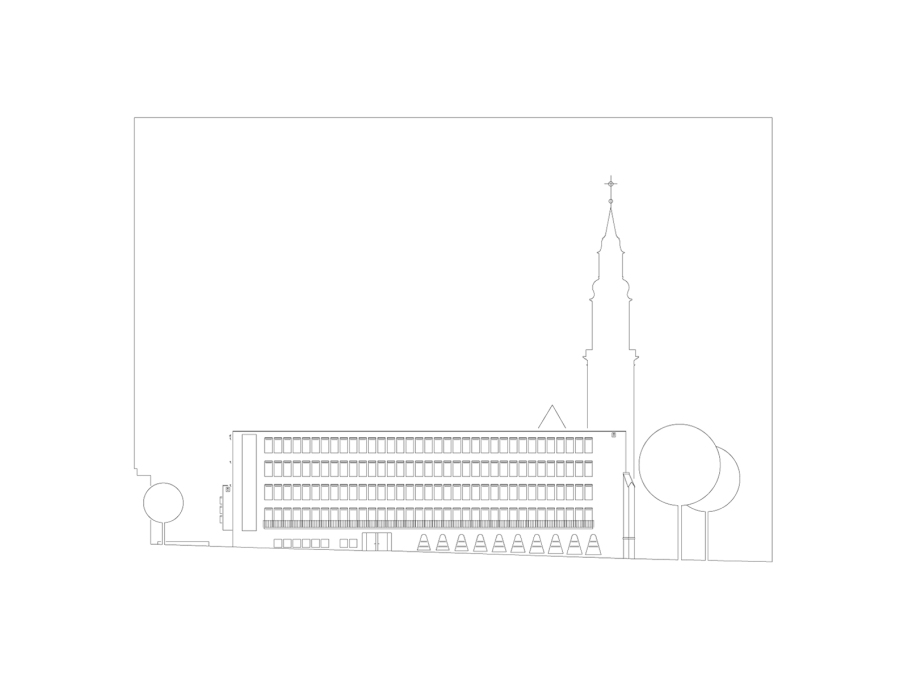

Instead of being a collage of buildings from different periods, here there is more a collage of different formal ideas. The practice of LRO Architects is well-known for designing formally expressive elements tailored to serve specific needs. Glazed bow-windows run along the façade on Büchsenstraße, each forming a niche in which internally a bench sits, facing the main lecture hall. Curved strips of concrete shelter the round windows that back onto the stage of this main hall. These can be closed by internal wooden shutters, meaning the stage can be daylit or not as required. Elsewhere shelters above other windows act like caps, serving both as sun screens as well as protective awnings, allowing the windows to be kept open in a tilted position even when it’s raining. Thus a certain, slightly awkward, formal obstinancy is combined with functional considerations. Only the fan-shape of the windows can’t be explained functionally. If this had been foregone, it would have calmed the exterior appearance of the building somewhat, the façade of which is clad completely in light, rose-coloured bricks, with a slight sheen to them.

The entrance has been relocated to face onto the courtyard, thus connecting it with the inside and utilising it as part of the public space of the building. Inside, the distinctive and expressive elements of the exterior façade are explained through what they relate to – how they connect inside and outside or the way they bring light into the rooms, exhibiting a consistency of functional design and detailing that seems to justify the enthusiasm of the client. Everywhere a limited palette of materials has been used: wood, concrete, white walls, and linoleum for the floors, some of it in contrasting red. The climax of the design is undoubtedly the main lecture hall, incorporating a gallery, and lit by a skylight with a series of curved wooden baffles below, resulting in a pleasantly diffuse light. Here, even in the roof detailing, you find a cheerful, open feel to the architecture that seems designed to underline the spirit of the institution and what it stands for. But the institution does not just stand for a friendly environment, but also for one that is socially and ecologically responsible. Thus only building suppliers who conformed to certain standards of employment and working conditions for their employees were commissioned, and wherever possible products from the local region were used, resulting in a highly efficient building in terms of embedded energy and energy use.

The next phase of the project, beginning in mid-2015, will see the church refurbished. But before then it seems likely that the new Hospitalhof will already have begun to establish itself as a new hub for the district. And this new building does seem to embody some of the values that one imagines the church wants to express: an openness to the world, balanced against the provision of a protective cultural and spiritual environment. Calmness without exclusion, cordiality without a chat-up line, openness without arbitrariness seems to be the message conveyed by the architecture. It is easy to understand the satisfaction of all involved.

– Christian Holl works as freelance editor and critic, and has published severals books. He co-founded frei04 publizistik with Ursula Baus and Klaus Siegele in 2004, and since 2007 is Curator at the Weissenhof Gallery for Architecture in Stuttgart.