France presents a nicely nuanced take on what in many pavilions became a bit of a modernist love-in at the Biennale. Norman Kietzmann reports on a show that technically and affectionately celebrates the architectural advances of the last hundred years, but doesn’t shy away from the down – and dark – sides too.

One of the first things to greet you inside the door of the French Pavilion is the figure of Jacques Tati’s Monsieur Hulot, one facet of France’s rich response to Rem Koolhaas’ theme of Absorbing Modernity 1914-2014. For instead of addressing the concrete buildings of the post-war period with documentary neutrality or wide-eyed admiration, curator Jean-Louis Cohen decided on taking a more differentiated view.

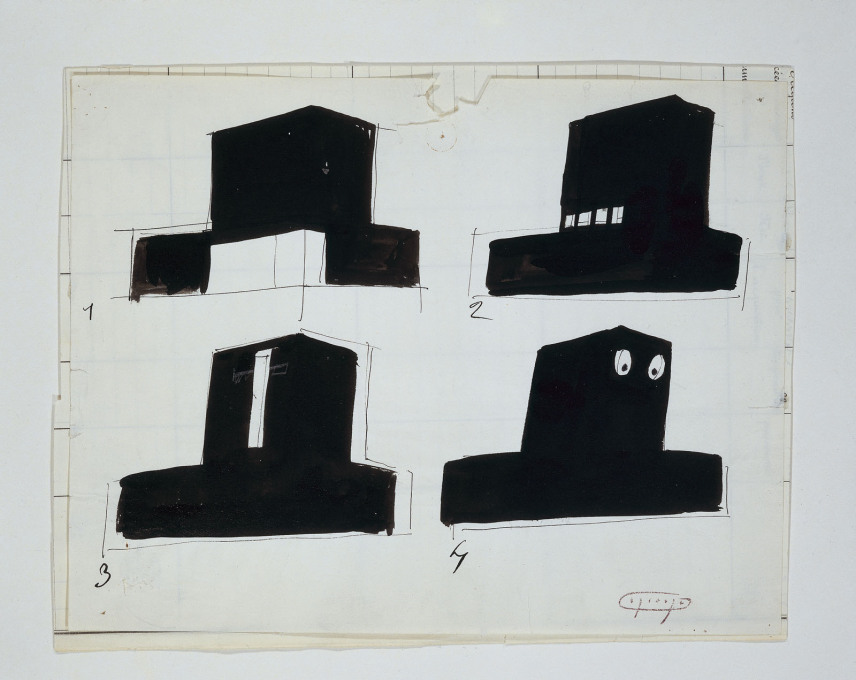

The exhibition Modernity, Promise or Threat? opens with a model of Villa Arpel from Jacques Tati’s film classic Mon Oncle (1958). The building is more than an architectural backdrop. Through the constant malfunctioning of its automatic doors, gate and other facilities, it itself becomes a protagonist in the film, and gains the upper hand over the life of its residents. In addition to a 1:10 model of the villa, on display are numerous sketches that were prepared for the film set by painter Jacques Lagrange, who was also a close friend of Tati. “After more than 50 years, Villa Arpel still stands for the dream of a life that is simplified through technology. Only sometimes this dream becomes a farce,” explains Jean-Louis Cohen.

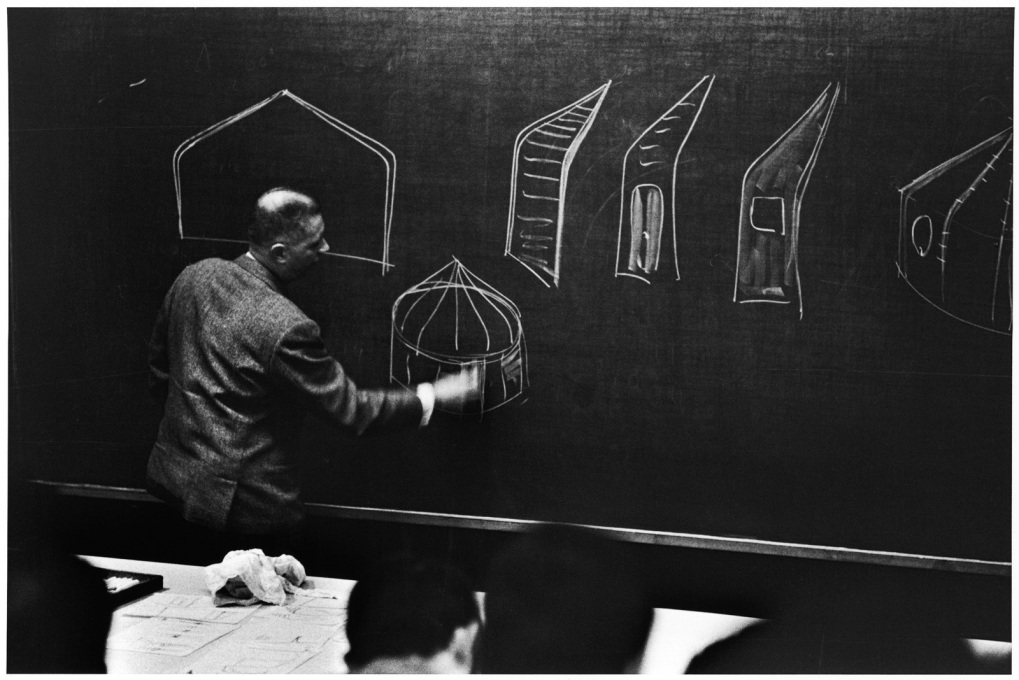

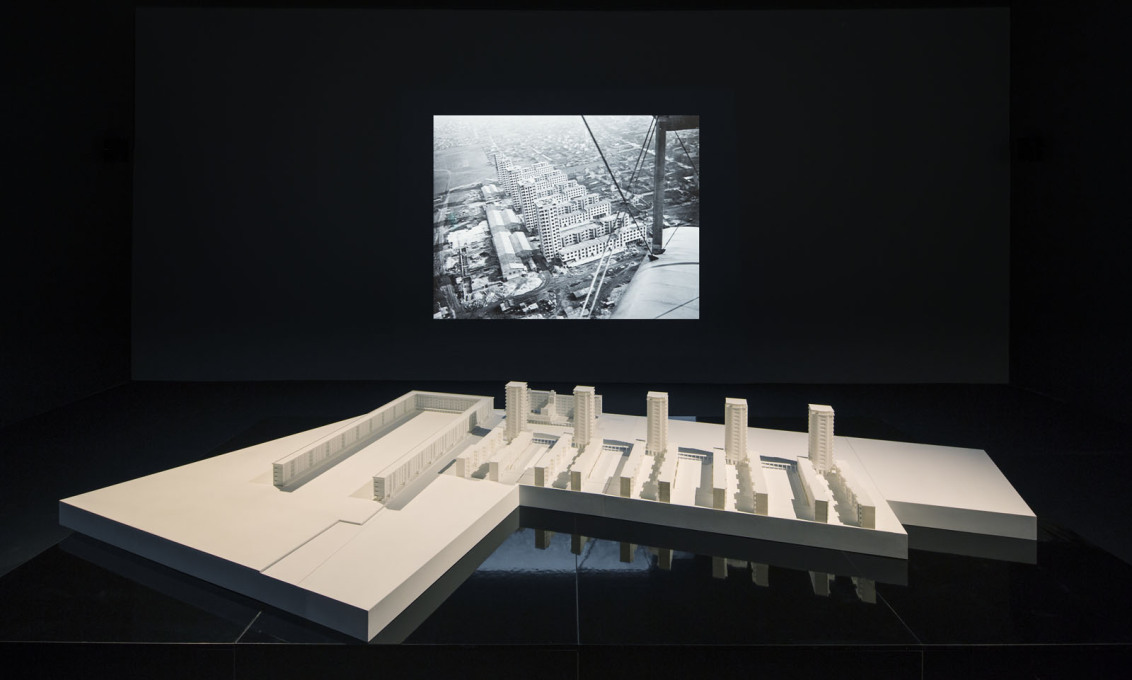

The other part of the exhibition leads from fiction into the reality of industrial construction. On the one side are Jean Prouvé’s mobile architectures, whose lightweight construction and refinement are showcased across eight wall panels. A look at the darker side of building begins just a few paces away. It was already in the 1930s that engineer Raymond Camus devised a prefab building system made from heavy concrete building elements. Two of these original elements hang from the ceiling in a further exhibition room, as if en route to the construction site.

Their purpose is demonstrated by a model of the residential housing project Cité de la Muette, which was erected in the Parisian suburb of Drancy in 1934. Its 14-storey tower blocks, recognised as being the first high-rise buildings in Paris, were constructed around a steel concrete frame covered with prefabricated panels. However, they were not used for their intended purpose until much later. The local police first used them as barracks, followed by the Nazis in 1940, who used the buildings as an interim prison for Parisian Jews before they were deported to concentration camps. Despite such strokes of fate, after the war the Cité de la Muette became the model for a 300 further housing estates erected throughout France – estates which have often become associated since with social fragmentation and unrest.

The exhibition’s various elements are woven together in a film by Teri Wehn Damisch, which is projected in all four exhibition rooms simultaneously. Fictitious moments, including scenes from Mon Oncle and Jean-Luc Godard’s drama 2 ou 3 choses que je sais d’elle (Two or Three Things I Know About Her) – where a block tower estate is re-constructed from consumer product boxes – mingle with the built reality. Interviews with residents reveal their sentiments on living on a housing estate. “I just can’t get used to how ugly it is”, says one young woman to the camera. Others, whilst impressed by the size of their apartments, detest the views outside their windows.

Herein lies the strength of the French pavilion: it is the only installation at the Biennale that presents architecture in the context of its users, and it allows them to speak – be it about a high-rise quarter at the edge of Paris or the upper-middle-class Villa Arpel from Mon Oncle. Jean-Louis Cohen has succeeded in balancing the aspirations and realities of modernism equally in a lively manner. It would be nice to have seen more such examples, where architectural flights of fancy are brought down to earth.

– Norman Kietzmann, BauNetz.