A new exhibition at the V&A, Disobedient Objects, examines the ingenious designs of protest movements. On display are objects of disobedience that range from benign-looking teacups that once spread the Suffragette movement’s message, to inflatables floated to block riot police, to more confrontational propaganda and homemade weapons. But according to reviewer Phineas Harper, as an overview it fails to address the crucial territory of political violence. Do romanticised notions of clever subversion serve to diminish the violent reality within which objects were originally forged?

“When pulling down a fence, always use a carabiner; never a grappling hook”. It’s early morning in late 2009. Members of protest group Climate Camp are unpacking ratchets, rope, spanners, spades and masks. The carabiner advice come from a teenager wearing a bandana and a frown who has clearly done this before – but it’s not until later, when the protest has been beaten back by an army of police that I understand the value of his advice. A team of activists are using a grappling hook to heave down the tall fence surrounding Ratcliffe Power Station when a police officer dislodges the heavy metal hook, which snaps back lacerating the front protestor’s forehead. Designed for rock climbing with a sprung clasp, a carabiner would have been harder to dislodge and less likely to injure. Repurposed, this humble item suddenly becomes an object of civil disobedience.

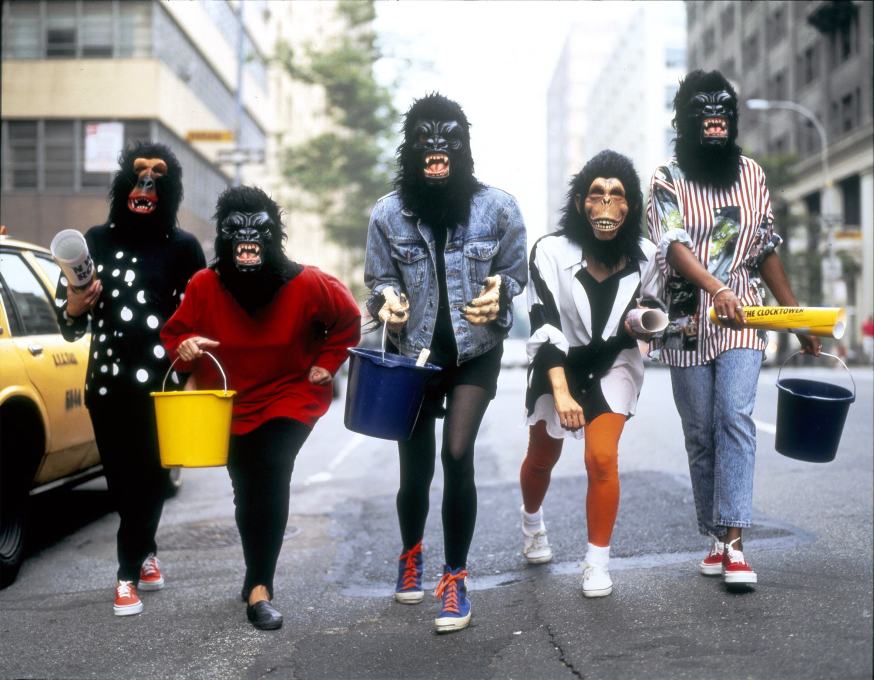

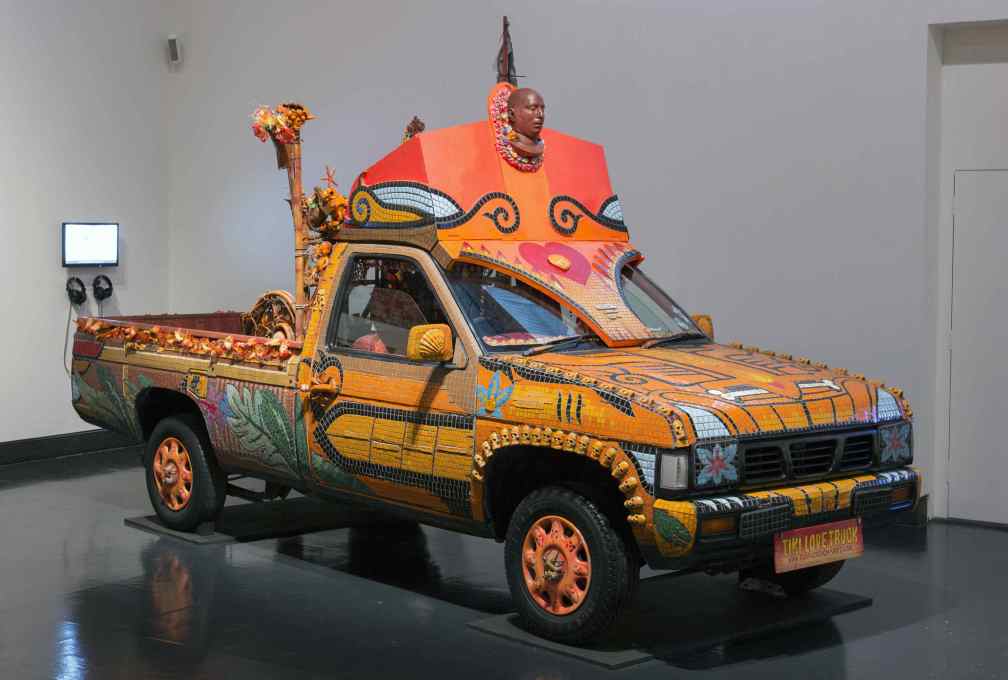

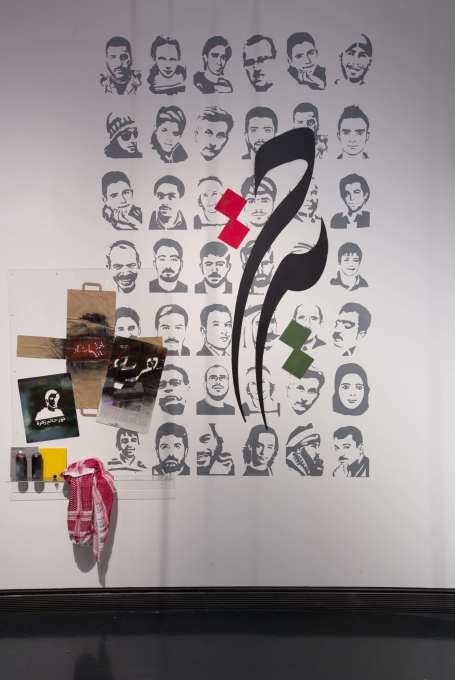

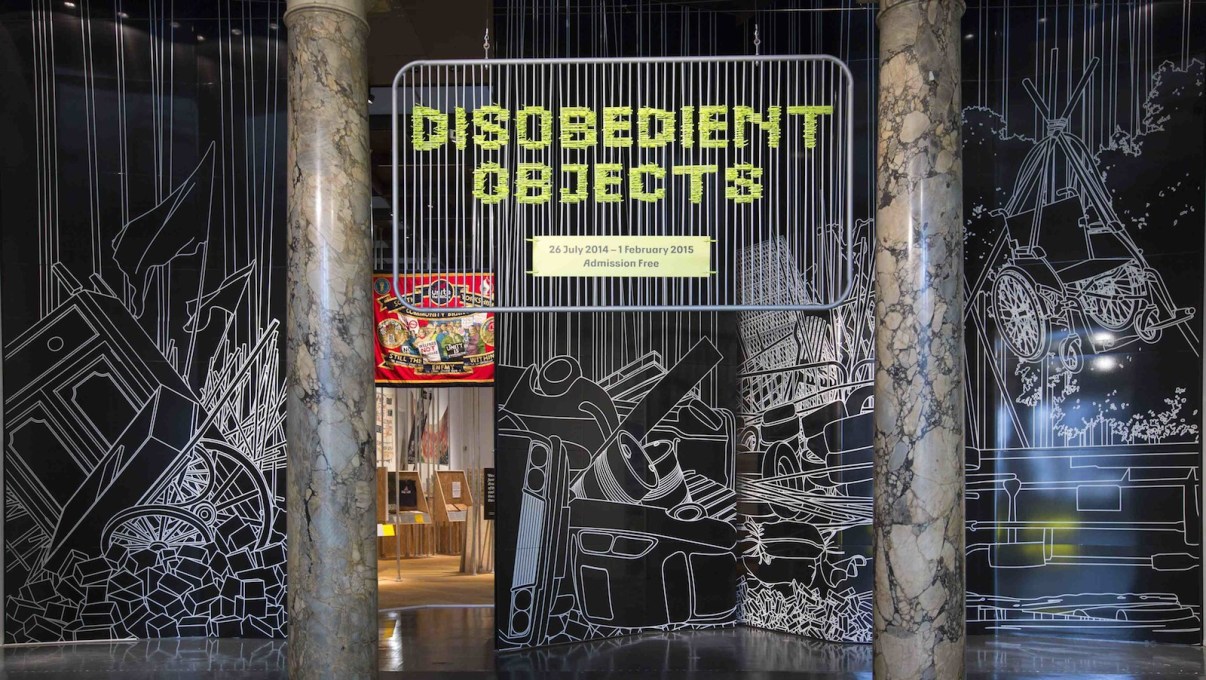

Disobedient Objects at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London gathers together such items from around the world. Graffiti-spraying drones adapted from remote controlled cars, teargas masks made from water bottles, riot shields fashioned from layered cardboard. It’s a rich collection of remarkable objects that paint a picture of human ingenuity in unlikely scenarios.

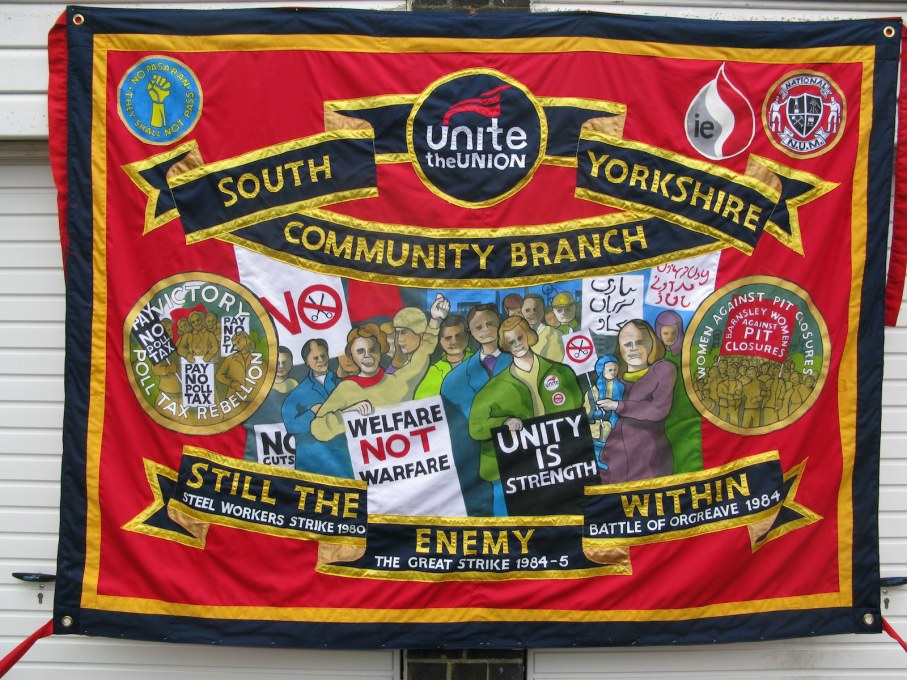

The show begins with a teacup emblazoned with the emblem of the Women's Social and Political Union, campaigners for universal suffrage in the 19th century. Besides luring conservative journalists who might otherwise have dodged an exhibition about protest, it makes the point that activism is neither new nor clear-cut. Many members of the Suffrage movement maintained links to the Nazi-sympathising British Union of Fascists, but for curators Gavin Grindon and Catherine Flood, the show is not about taking sides. They reject the “rigid geometric scheme” of the modern Left/Right binary, recognising the story of political dissent is much older.

The phrase “go the extra mile” comes from a biblical example of civil resistance. During the Sermon on the Mount, Jesus advises oppressed Jews that if a Roman “forces you to go one mile, go with them two miles”. While this lesson is widely taken as advocating the meek acceptance of authority figures, theologian Walter Wink advocates an alternative interpretation: in first-century Judaea, Romans were legally entitled to demand Jews carry items for up to one mile, but any further than this and the Roman could be prosecuted. A Jew going that extra mile committed no crime themself, but turned the tables of power on the Roman, who had to wriggle out of a potentially humiliating scenario. Jesus, therefore, is not talking of cowed subservience but of finding sophisticated legal loopholes to destabilise power dynamics between oppressors and oppressed. This theme of legal subversion underpins many objects on show.

High above the exhibition, giant inflatable silver cubes hang from the ceiling. Produced by Catalan protest group Eclectic Electric Collective, they are tools of comedic destabilisation, which protestors tossed at cordons of police during the 2012 General Strike in Barcelona. With their path blocked, the officers faced a conundrum: would they attempt to deflate and remove the cubes, a slow and potentially farcical process, or throw the cubes back, inadvertently instigating a surreal game of volleyball, punching giant inflatables back and forth like balloons at a children’s party? The power of playfulness to undermine the establishment is celebrated throughout the show yet the thesis becomes decreasingly coherent towards the less passive end of civil unrest.

There is little interrogation of the critical threshold where civil disobedience becomes violent revolt, though it is here that the most challenging questions lie. The exhibition includes, for example, a Palestinian slingshot, made from a child’s shoe. It is categorically a weapon designed to harm but the way it ingeniously subverts its original purpose is inherently fascinating like watching Macaulay Culkin as Kevin McCalister rigging deadly booby-traps from household objects in Home Alone. But if a Palestinian slingshot is a valid inclusion, isn’t a Hamas rocket, which are often equally homemade? Similarly, the curators have highlighted a Chinese farmer who defended his land from state bailiffs with a home-made rocket launcher. We cheer for the brave underdog standing up to the might of the Chinese state; but what if he had simply bought guns from a shop? The overt fascination with romantic repurposing over efficacy suggests this exhibition is primarily interested in aestheticised activist upcycling: taking apart familiar objects and hacking them together in novel ways with a political twist. Guns are demonstrably effective objects of disobedience, but their mass-production is at odds with the overarching presentation of low-budget “craft-ivism”.

Bavarian sociologist Max Weber defines a state as any community which effectively commands a monopoly on violence. For Weber, the so-called “grassroots” and “establishment” exist across a single spectrum of power struggles. Arguably the designs in this exhibition are neither objects of disobedience nor obedience, but simply objects of agency tuned to their creators’ circumstances. The curated shoe-slingshot is ultimately as much a designed object of social control as the un-curated tanks it is used against.

– Phineas Harper is Assistant Editor of The Architectural Review.

Disobedient Objects

until February 1, 2015

Victoria & Albert Museum

Cromwell Road

London SW7 2RL