The original “soft machine” was William Burroughs’ term for the human body in his eponymous novel from 1961. Science journalist and artist Claire L. Evans takes a fresh look for uncube at the mechanistic metaphor and the “building” work we have been practicing on our own bodies ever since.

In the 1961 Terry Bisson short story, They’re Made Out of Meat, two aliens sit around having a baffled conversation about strange life forms they’ve just discovered in a routine survey of the galaxy.

“They're made out of meat”, the first alien observes to the second.

“Meat?” the second answers. “That’s ridiculous. You’re asking me to believe in sentient meat.”

The aliens cannot wrap their minds around the idea that something made of meat, organic all the way through, might have the capacity to think, to dream, and to love. How could something with no mechanical parts, no hardware, possibly be capable of thought? Of course, the life forms these aliens have discovered are none other than human beings.

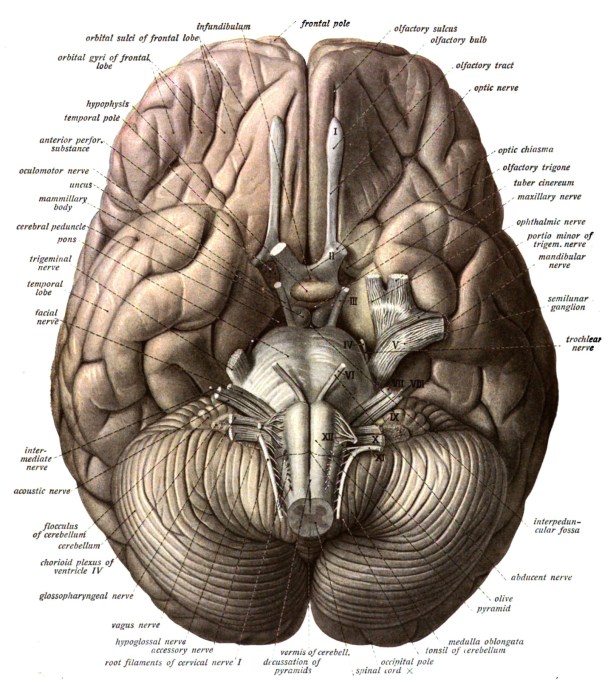

A few years before Bisson’s story was published, the pioneering Artificial Intelligence researcher and cognitive scientist Marvin Minsky made a quite shocking pronouncement about the nature of human intelligence. “The brain”, he declared, “happens to be a meat machine”.

Minsky’s statement was meant to provoke, but it’s not untrue. Although we tend to associate the word “machine” with engines, pistons, and clanging metallic components, the brain is an electrical and chemical mechanism – a kind of machine whose behaviour can be explained in electrochemical terms. As a computer, the human brain is a capable piece of hardware: our 100 billion neurons, laced together with (roughly) 1 quadrillion synaptic connections, make up the most powerful processing system in the world, far more plastic and nimble than any piece of silicon.

That the brain is a computer – made of meat – is only the most recent iteration of a seemingly inescapable human tendency: to draw from existing technologies to illustrate the mechanisms of the human organism. The fountains, pumps, and water clocks of antiquity underlie the Greek pneumatic idea of the soul, just as the telegraph served as an operating metaphor for our nervous system, pulsing signals from mind to the peripheries of the body, like Morse code tapped out on cables beneath the sea.

Only in recent years, however, have we have begun to supplement such metaphors with more tactile connections between mind and matter, plugging technology directly into the human meat machine. Modifying and enhancing our bodies with technology is relatively common. Cochlear implants, neural implants, and pacemakers are now routine surgical interventions in modern hospitals and the field of prosthetics is developing rapidly. Researchers in the United States, combining myoelectric limbs and nerve transplants, have even developed robotic prosthetics which allow patients to feel objects by touch.

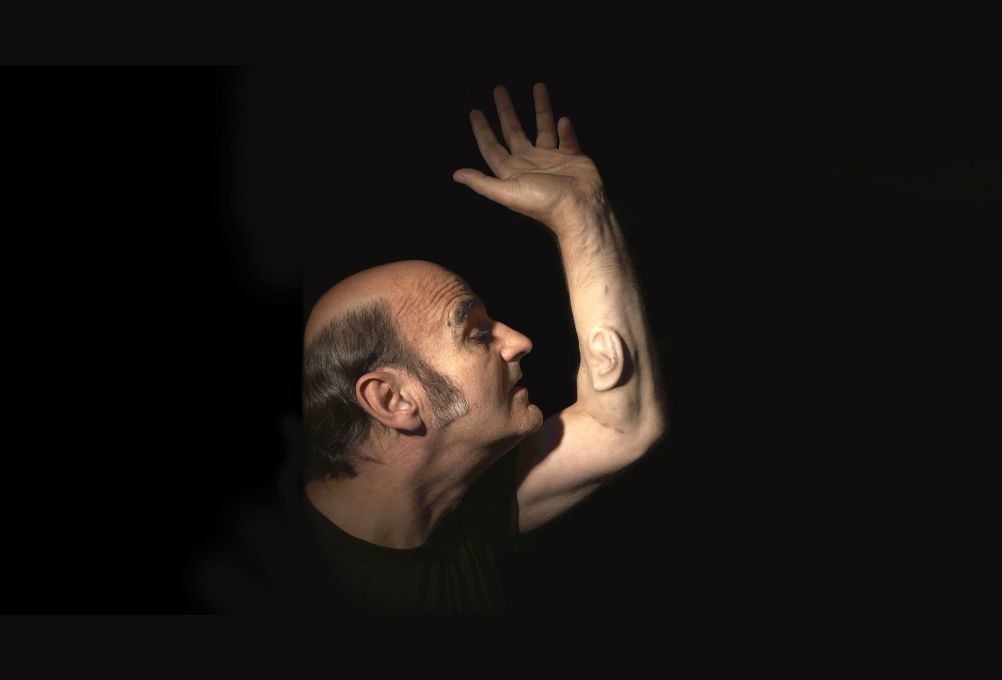

The Cypriot-Australian artist Stelarc has argued that the human body is obsolete. That our hardware, the result of random evolutionary processes, has reached the ceiling of its capacities, and must now be supplemented by the creative integration of technology into the body itself. While his works – which employ flesh hook suspensions, robotic appendages, and, most famously, the 2007 surgical attachment of a cell-cultivated human ear onto his forearm – may seem extreme to most mainstream sensibilities, they demonstrate what is possible when the boundaries of the body are transcended by the limitless capacities of the technological imagination.

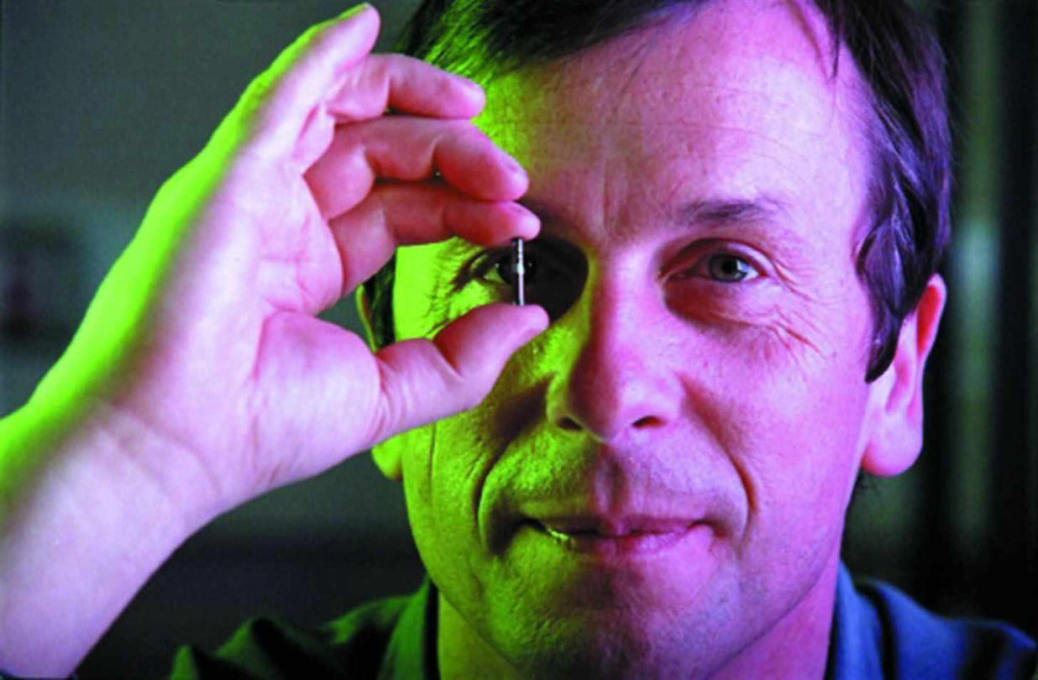

Many other artist-researchers have echoed Stelarc’s sentiments. Steve Mann, a pioneer of wearable computing, has been living as a functional cyborg since the 1980s, wearing a computer vision system of his own design. The synaesthesic cyborg Neil Harbisson, who was born completely colour blind, had an antenna implanted into his skull that allows him to perceive colours (the infrared and ultraviolet spectrum) as sound waves. He also founded the Cyborg Foundation in 2010, which lobbies for cyborg rights. The British scientist Kevin Warwick successfully linked his nervous system to the internet through the surgical implantation of an array of electrodes. Using this meat-and-hardware combination, Warwick has been able to extend his sensory mechanism over the internet to control a robotic hand, a loudspeaker, and an amplifier.

Experiments in personal enhancement of this nature tend to be self-motivated and self-funded. Mann, Harbisson, and Warwick have received varying degrees of institutional support, but they are ultimately their own guinea pigs, hacking the only meat machine to which they have unfettered access. At the extreme end of this tendency is a growing community of biohackers or “grinders” who take transhumanism into their own hands, for instance by implanting rare earth magnets into their fingertips in order to “feel” the electromagnetic spectrum.

Even without advanced prosthetics, magnetic fingers, or telepathic connections to the internet, tens of thousands of mundane cyborgs walk among us. After all, eyeglasses are a technological enhancement, as is the systematic consultation of a handheld device containing the sum total of the world’s accessible information. Wearable technologies like Google Glass, pedometers, and other health-tracking tools are increasingly common. Very few people in the developed world live entirely unmediated by technology.

As Terry Bisson wrote, we may be meat, but we are “thinking meat, dreaming meat”. Meat that dreams beyond meat.

– Claire L. Evans is a writer and artist working in Los Angeles. Her “day job” is as the singer and co-author of the conceptual disco-pop band YACHT. A science journalist and science-fiction critic, she is a regular contributor to Aeon Magazine, Vice, and Grantland, and is the Futures Editor of Motherboard. A collected book of her essays, High Frontiers, is now available from Publication Studio. www.clairelevans.com