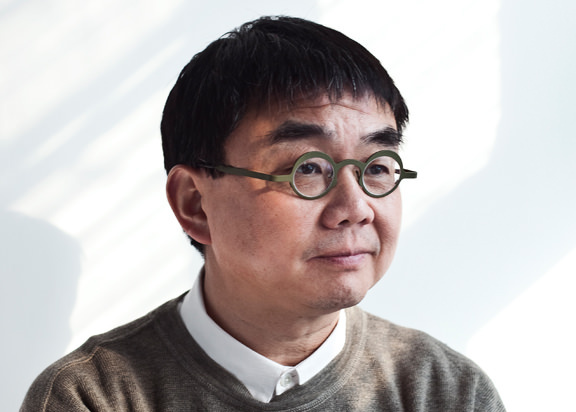

Yung Ho Chang founded China’s first independent architectural office, Atelier FCJZ, in 1993. He is also an experienced educator who has taught in both the US American and the Chinese architecture school system at the highest level. He currently teaches at MIT, Tongji University in Shanghai and Hong Hong University. In an exclusive interview with uncube as part of our School’s Out education issue, Yung Ho Chang explains his highly practical perspective when it comes to architecture education, gives an insight into what he sees as the main differences between the European, US and Asian models and why students need to be taught how to “do it right”.

Mr. Chang, would you agree with Odile Decq that it is time to fundamentally rethink architecture education?

It is certainly true that the curriculum of most architecture schools is behind the developments within the profession. Especially in the US and in China, schools are much too embedded in theoretical discussions, which of course relate to real-world issues to some extent, but the way we discuss these issues within the university remains very abstract. It doesn’t prepare students for work after their studies.

Let’s take the way digital technologies are being taught as an example. I am under the impression that students learn how to use digital technologies in school in order to create forms, but this is not actually the main point of using them; they enable us to process a massive amount of information, which is what architects should learn how to use them for. So the topic is right, but the focus of many professors is not.

This sounds like it’s related to your time as head of the architecture department at the MIT?

At MIT we had both: colleagues who were primarily interested in creating complex forms, and others more interested in cutting-edge technologies like 4D printing. In a way these projects have a much deeper focus on technology and on the technological progress – and that’s what it should actually be about. If we want to move architecture forward as a discipline, we should look at how technology is changing, not just ways in which to produce more complex forms.

By saying there is a gap between the education and profession at most architecture universities, do you mean that the main duty of universities is to produce professional architects?

No. The problem is not the gap, but the deeply different understanding of what an architect does; what he or she has to know and learn and ultimately what architecture is all about. At many universities in the US I almost get the impression that “building” is a forbidden word; to many professors “building” seems too profane, too functional, too practical to teach. They only say “architecture”. Yet what is interesting about architecture to me is “building”, both as a verb and a noun. So when I teach, my studios are always about concrete, bricks, a budget and a building – from there on, of course, we stretch the course to “architecture”. This way it doesn’t become sort of a metaphysical idea, as it so often does in schools in the US.

Is it different in China?

Yes, in China we have very different challenges. Chinese education came from the Beaux Arts tradition, yet with the opening of the country over the last 30 years or so, this system has never been challenged but rather altered a bit here and there. Today Chinese education is a hodgepodge of different approaches with two main problems.

One is that architecture education is too closely related to reality of the business, which means that sometimes it is enough for a student to learn how to do renderings in order to get a degree and a job. The second problem is that the Beaux Arts tradition doesn’t pay attention to progress in building technologies. So students learn a bit about contemporary theory and, via magazines, they know a bit about the latest projects of international starchitects, but they know very little about how buildings are actually put together. Sometimes they are not even interested in the physical building at all anymore, but only focus on the discourse and the images that architecture produces.

European models of higher education – including architecture – are getting more and more standardised by current laws like the Bologna process.

Yes, that’s true. It seems European education models have started to move in the direction of the US system and I believe that this is wrong. Europe has such a long educational tradition and in terms of studying architecture I believe European education is much more healthy, as it offers a good balance of construction, building and theory.

Is there any architecture school in Asia offering a similar approach?

There are some good examples of architecture schools in Asia. Yet for a comprehensive understanding of architecture, I would still recommend students to go to Europe. I think many universities in the US and in China too have improved the balance of engineering and design within their curriculum in recent years, yet students still only get an idea of structures and construction after they’ve learned to design first. I learned like that, too. It took me many years of practice to understand that it should be the other way around.

What would be your ideal system for how to teach architecture?

If I had to design a new curriculum, I would do two things. In the first years, during the design training, I would always ask students to do big things, like full-scale models. And I would also ask first-year students to take extra structural courses. Actually, there was a good system at the AA in the 1980s – they would have one studio with two professors, one being an architect offering a broad idea about architecture, and another on the practical side with a lot of professional experience, who could help the students to realise these ideas. This is a great way to get students to work on ideas and their realisation at the same time.

Zaha Hadid studied at the AA in the late 1970s or early 80s, and she developed these very interesting drawings and forms which were always very closely related to building structures; they contained both a spatial or artistic idea and an understanding of how to build it. To a limited degree, we did something similar when I was at MIT. We had structural engineers participating in our studios, but we were unable to alter the existing system enough – partly because the engineers were always too busy to participate in the design studios since they had to teach their own courses.

So one main issue for you is combining architecture studios with other disciplines to encourage interdisciplinarity?

Yes, but it’s not about interdisciplinarity for the sake of developing new ideas; it’s about doing buildings right. If I see a student’s work that is great architecture, but he or she never thought about how the building could be ventilated, than it just cannot be right. It’s only half-baked. You cannot add these technological devices later.

I live in a well-designed apartment building in Beijing by Baumschlager Eberle architects from Austria. The building’s mechanical system operates entirely within its sheer walls and slab concrete structure, and I can’t imagine they laid out these spatial ideas without knowing exactly what kind of structural systems would eventually go into that building. The structural and the architectonic idea work together with the mechanical system really well – which is totally different from the American way of designing architecture. I hope that Dietmar Eberle reads this!

Currently you hold two teaching positions besides MIT, one at Tongji University in Shanghai and one as visiting professor at the Faculty of Architecture at Hong Kong University. What is your experience with the pedagogical systems of these universities?

I am less involved with designing the curriculum at Tongji and Hong Kong universities than at MIT. But both have curriculum problems. At Tongji for instance, there is a lack of systematic rethinking of the curriculum. At Hong Kong University, there is too much American influence. American schools tend to value complexity a bit too much – sometimes only for the sake of complexity, which does not always produce the best architecture, at least in my opinion.

I am also teaching very different courses at each school. In Hong Kong, where more than 90 percent of the built structures are concrete, I am teaching a studio about concrete, where students pour full-scale concrete models. In Shanghai I am doing a seminar about the notion of craft in architecture. For some reason I find the students in Hong Kong are more obedient while the Shanghai students seem to be much more diverse and cosmopolitan.

If you were to recommend an architecture school in Asia which one would it be and why?

I would recommend two! In China, I’d recommend Southeast University and Nanjing University for the simple reason their students tend to have the best portfolios. There is a certain sense of building in their work, not only of pretty images; they seem to know something about materiality and space. To me this is comparable to students from the ETH Zurich, although the depth and the quality of the work is very different.

The other programme I would recommend is the Waseda in Tokyo, a major private university. There they put all the first-year students in architecture, lighting, mechanical engineering, and structural engineering, together. They all start with the same courses and only afterwards are they separated into their specific disciplines. If we are not talking about something radically different, but about a well-organised university with good balance, I think both Hong Kong University and National University of Singapore are at the top.

If your children wanted to become architects and asked you for guidance, what would you tell them? Would you recommend going to university at all?

I don’t have any children, but my father was an architect. In the beginning I wanted to become a painter – but I was no good at painting. In fact, I was really bad. I was also no good at science at school, so my father said: “maybe you should consider doing what I do – it’s a good combination of everything and you don’t need to be good at anything”.

So hypothetically, if my wife and I – who is also an architect – had children who were interested in architecture, I would suggest that they study anything they are interested in for an undergraduate degree. Then they should come to our office afterwards to work with us for a few years, because I do think someone could become an architect just by working in an office. When I was teaching at Peking University, I saw that people who were working as interns in our office learned a lot more and faster than the students at the university.

I do have a nephew and a niece who are 10 and 11. Let’s see how they develop! I have tried to influence them a bit to do something artistic and creative, and if they are interested in architecture or something similar someday, I’ll definitely invite them to work in my office.

– Interview by Florian Heilmeyer

Further reading:

School’s Out: uncube issue no. 26

An Ecology of Technologies: Interview with Hitoshi Abe