As part of our Australia issue No. 27 uncube commissioned Australian ex pat architecture and urbanism curator Rory Hyde to share one of his favourite Aus oddities. He chose the humble private dwellings and experimental structures of Roy Grounds, architect of the giant Shine Dome (1959), National Gallery of Victoria (1968) and controversy-plagued Melbourne Arts Centre (1960s-70s). They reveal an intriguing play of opposites between macho, representative, new internationalist architecture and hobby home builder.

A cube, a dome, and a pyramid are arranged in a line. Made of timber, sheet metal and canvas, their crisp geometry stands out against the scrubby coastal bushland they occupy. Domestic in scale, these structures appear at once to be a part of the landscape, and yet alien to it. Cosmic geometries imposed on an ancient terrain.

Built by Roy Grounds (1905−1981) in the mid 1960s on a coastal plot at Penders Beach, halfway between Sydney and Melbourne, these three structures are evidence of unselfconscious creativity. Private sketches, simple yet profound.

This was serious play, with serious aspirations. In these three structures we can see Grounds reaching toward an Australian vernacular, this architecture looks to the first shacks of the European settlers, unfussy and improvised.

The most exciting of the structures is the geodesic dome. Unlike the crisp precision of Buckminster Fuller’s domes in America, Grounds’ dome is made of salvaged timber struts, with tin rubbish bin lids serving as the junctions. The dome becomes heavy, muscular, and odd. Through the process of importation, Fuller’s rigorous mathematical form takes on the “she’ll be right mate” attitude of the Australian outback, as if built by a bush mechanic from a set of incomplete plans, obscured by red dust.

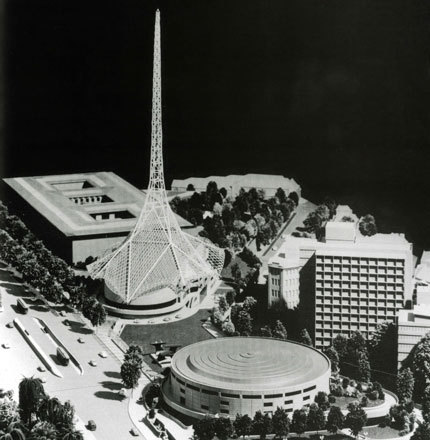

Max Delany, curator of contemporary art at the National Gallery of Victoria, pointed out to me the similarity between these three informal timber shelters and the enormous urban complex of Melbourne’s Arts Precinct. A cube, a dome, and a pyramid are arranged in a line. Just like the cube of the NGV, the dome of the Concert Hall, and the spire of the Arts Centre. Up on the New South Wales coast, Grounds built these three ad-hoc structures as a prototype for the largest cultural precinct in Australia. Lining up these structures in his mind, he was operating at the scale of a tent, but thinking at the scale of a city.

Awarded in 1959, the Arts Precinct ought to have been cause for celebration, but soon became a source of conflict and anxiety. In 1962 Grounds split from his partners Robin Boyd and Frederick Romberg, taking the commission with him. Penders became Grounds’ private bolthole, far away from the ringing phones, needy clients, stiff collars and burned bridges. Grounds found refuge back in the remote bush, a place of freedom to think and to play.

Photos of Grounds reveal him to be a man of power and authority, unquestionably the one for the job. A club man, a solid build, with cigar in hand, holding his own with the money men of Spring Street, able to convince them of his vision simply through gravitas, without resorting to salesmanship.

But this image of self-assurance stands in contrast with the tinkerer up on the coast, of somebody reaching for an idea, of quiet experimentation. Grounds’ primitive geometries suggest he sought something cosmic, even mystical. Inside the tough businessman was a new-age dreamer looking to the stars, not the history books, to myth, not science.

– Rory Hyde is curator of contemporary architecture and urbanism at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London.