As part of our Australia issue addressing Antipodean architecture and beyond, local architect and writer Andrew Mackenzie delivers an in-depth, insider view of an emerging post-modern sense of “Australian-ness” emanating from the city of Melbourne and finds that whilst Sydney may still be following the “Miesian" path, Melbourne architects are striking out along a path of ad hoc, drunken geometries that have their roots in the exoticism of the suburbs.

Despite the best efforts of technology to reduce everywhere to anywhere, the local just will not go away. This makes the business of ascertaining a coherent national architectural culture rather complicated. More often than not, the local just queers the national pitch. To make matters more confusing, it is often the case that a community finds greater affinity with another community on another continent than with a neighbouring city. This is certainly true of the architectural cultures of Melbourne and Sydney, the habitués of which largely find greater kinship with Madrid or Riga than their counterparts in either city.

The relationship between these two cities is not just a difference in cultural nuance or aesthetic variation, like one preferring off-form, or the other precast. It is a vigorous and ingrained antipathy, which, as so often is the case, begins and ends with how each city has digested modernism.

The conventional narrative goes like this: In Sydney the lifestyle is pleasurable and the architecture abundant, at least in the Miesian sense. Materials often do what they want, thanks to Kahn, so long as everything fits into a grid. Melbourne, on the other hand, has adopted the oyster principle, welcoming the grit of complexity while demanding its architecture exceeds good taste and minimal detailing. Geometries often look drunk while materials tell stories. This narrative is not wholly specious, though inevitably it does quietly erase many exceptions.

There are many reasons why Sydney fell so thoroughly in love with modernism and remains so. But why has Melbourne’s relationship with modernism been so conditional?

One good place to start is on the outskirts of the city, at a time when open fields of native grass were being transformed into neat quarter-acre blocks, ready to accept tidy brick boxes for new Australians. While the architecture schools of Australia were first imbibing the modernist dream of universal order and rational top-down urban design, another force was asserting its ineluctable market-friendly dominance. Organic, ad hoc and barely controlled, a new urban formation was desperately keeping up with incoming immigrant demand – more like viral self-replication than the orthogonal discipline of a masterplan. We’re talking, of course, about suburbia.

It is notable that Australia’s first narrator of suburbia’s qualities was the Melbourne architect and writer Robin Boyd. In his seminal 1960 book The Australian Ugliness, Boyd took aim at suburbia’s veneer of verisimilitude, its denial of material truth, its abuse of nature and most of all its “featurism”. Boyd loathed all the fakery of decoration – of classical columns, Georgian windows and Tudor beams, of Californian light and Gothic dark, of patterned brickwork and ornamental chimneys that never saw smoke. Indeed Boyd’s book might more accurately have been entitled Australian Fancy.

Boyd’s intention was to lambast a national habit, by then well-established, of copying the styles and features of Europe and America, then degrading them into pale pastiche replicas. Boyd was one of a number of lightning rods who from the 1960s to the 1970s sought to focus the nation’s discontent with a second-rate, second-hand identity. In a profound way the writings of Robin Boyd, along with novelists like Patrick White and satirists like Barry Humphreys emboldened a new generation to think about what it meant to be Australian. With the establishment of the Australia Council for the Arts in the 1970s, along with Labour’s generous funding for Australian film and television industries, it was a good time to ask the question.

For some Melbourne architects the question of Australian-ness found an answer quite simply in not being mainstream. Australia is, after all, a country at the margins. Ironically, it was Boyd’s appeal for a new, truly honest exploration of national identity that led these architects to reject second-hand imported modernism and forced them to look at Australia’s peripheral condition, both in the world and as if by analogy, in its suburbs. Boyd’s cri de coeur paved a way for a generation of Australian architects to lift a mirror to the nation in a manner he’d not entirely intended, embracing cultural forms that the architectural mainstream wanted to ignore or reject. This amounted to precisely the suburban flotsam and jetsam that Boyd so fiercely criticised.

Here the story of Melbourne’s “split” with Sydney takes a decisive turn with the return of the Melbourne architect Peter Corrigan from America, where he’d studied under Robert Venturi and worked with Philip Johnson. Arriving back in Melbourne he partnered with his wife, Maggie Edmond, to form Edmond and Corrigan. They produced a sequence of buildings throughout the 1970s and 1980s that generated discussion and debate in Melbourne and castigation and rebuke from Sydney. Now somewhat indiscriminately thrown into the post-modern basket, the work of Edmond and Corrigan is more accurately the product of what architect and writer Ian McDougall calls a “dedication to Arte Povera radiance in the suburbs and exoticism in the city”.

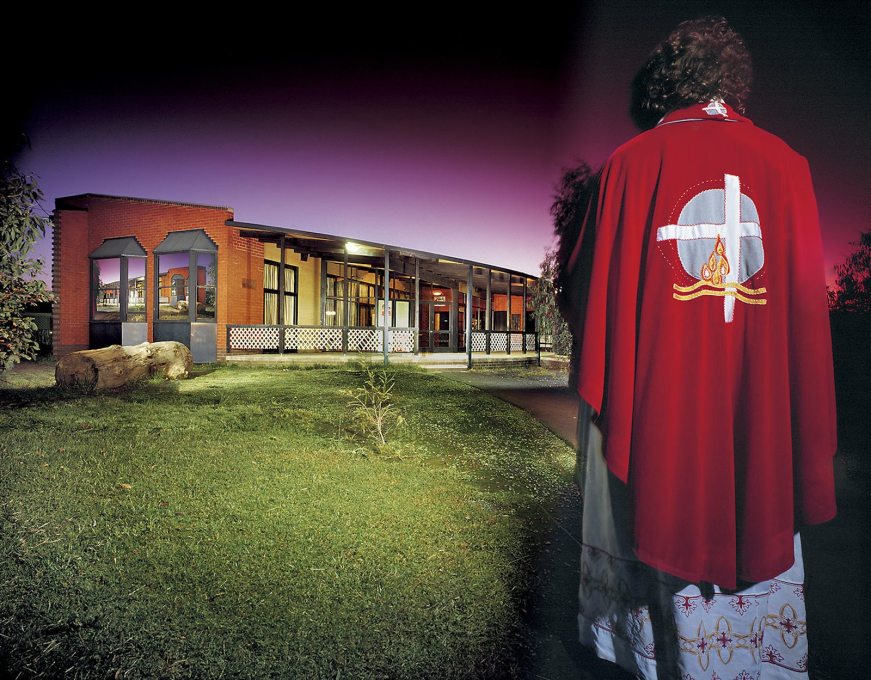

Edmond and Corrigan’s Church of the Resurrection in Keysborough set the gold-coloured standard back in 1976. Though modest in scale, it bears all the hallmarks of their later work: the insistent localism, the cheap-seats theatre and the rejection of modern Puritanism. Sixteen years after The Australian Ugliness, Keysborough extended a hand to suburbia and welcomed it into the fold. It declared that suburbia does indeed have a genius loci and that spirit is one of bits and pieces – of an environment built on the fly. This too is Australia.

Later Edmond and Corrigan’s RMIT Building 8 would push the eclecticism of Keysborough to new heights. Though highly ordered and decoratively disciplined, it was also one large collage of forms and materials referencing Melbourne’s architectural past, from the exuberance of Walter Burley Griffin’s Capital theatre to the modern gothic delights of the Manchester Unity Building. At a time when Melbourne’s downtown was slowly being transformed into a grey undifferentiated valley of steel and glass, this cri de coeur declared a resistance to the global dead hand of the curtain wall. It also firmly established Edmond and Corrigan as the catalysts of a new direction for architecture in Melbourne.

Many acolytes and splinter groups ensued, but the two practices that carried the torch most boldly were Ashton Raggatt and McDougall (ARM) and Lyons, practices that notably have since worked all over the country, from Perth to Adelaide, Brisbane to Canberra, yet neither found fortune in Sydney.

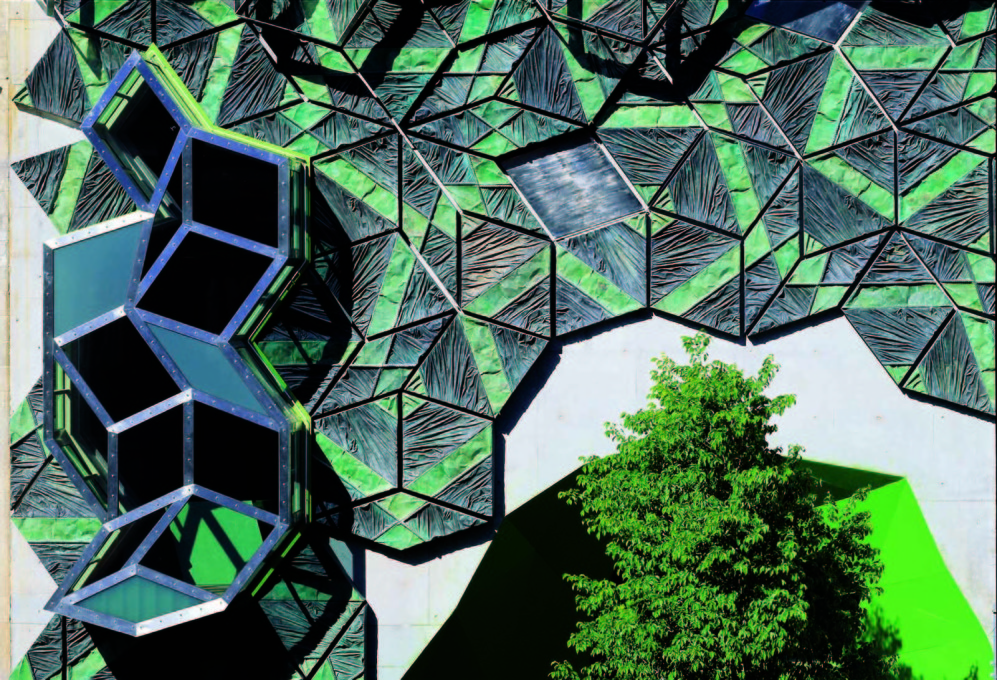

The project that first launched ARM into the territory of awards and press was RMIT University’s Storey Hall. It sits almost immediately adjacent to their mentor’s masterpiece, Building 8, and has engendered as many discussions, in both praise and reproach. Unlike its more disciplined older neighbour, Storey Hall is a riot of forms and historical references, or more accurately perhaps memories. As Ian McDougall writes, “for me, the question of the Local deals directly with the significance of memory”. Here the memories disinterred and reworked into the fabric of the building include references to the suffragettes who once met there, as well as local Irish-Australian history, in the abundant use of green. Though some see this fragmented whole as early deconstruction, its messy mix of cultural narratives is an anathema to the ascetic formal constructs of Peter Eisenman.

While ARM and Lyons have, between them, since produced museums, apartments, sports stadia, offices and retail complexes the length and breadth of Australia, the fact that the latter practice has recently completed a new building, Swanston Academic Building (SAB), also for RMIT, just opposite Building 8 and Storey Hall, demonstrates how this dynamic institution, and its doyen of architecture Leon van Schaik, has significantly fuelled the trajectory of Melbourne’s complicated relationship with modernism.

The Lyons team took the site for SAB, smack bang in the middle of Melbourne’s Central Business District, as their starting point. Wanting it to have a conversation with its surroundings, they identified a series of key landmark buildings in the city, mapping lines between them and the site. These lines were then thrown into a software programme to generate the shapes and form of the building. Then a photographer was hoisted up on a crane to photograph the panorama of views, in order to determine the best vistas, thus locating key façade apertures. No elegant hand-drawn parti required. In place of one inspired genius, was a collective design team.

Younger practices have evolved in recent years whose work owes a debt to this Melbourne lineage. Ideas percolated through university buildings and museums now find expression in houses and small projects, such as the Wattle Avenue House by MvS Architects, which plays with vernacular, channelling Corrigan, (who taught both partners: Paul Minifie and Jan van Schaik – son of Leon),and the series of extraordinary housesby Cassandra Fahey. The latter take’s suburban exoticism to a new level, attesting to ornament’s enduring affront to modernism’s sense of decency. As AA’s Mark Cousins has said, “just because Loos wrote Ornament and Crime doesn’t mean he was saying ‘don’t do it!’”. Melbourne, like fin-de-siècle Vienna, also enjoys the delicious relationship between illicit behaviour and good times.

Paul Morgan Architects mines a different seam at the margins of modernism, through a body of work that owes a debt to Stanley Kubrick and John Lautner, transposed to an Australian sense of scenography. The secondary schools of McBride Charles Ryan display an uncommon exuberance in materials and form, exploiting multi-coloured feature brickwork and curved sensuous forms to conjure a sense of delight out of state government thrift.

But this briefly sketched lineage does not represent the primary, even dominant, architectural culture of Melbourne. Plenty of Melbourne architects still obey the golden section and pay their dues to function, and many other lapsed modernists explore other heterogeneous tangents. And then there’s Sean Godsell, the lone arch-modernist who stoically accepts his role as an Ayn Rand-style taciturn, square-jawed hero.

What’s clear, however, about this particular not-simply-post-modern local trajectory, is that it is so trenchantly and unrepentant different from the continuing legacy of well-mannered modernism: making it stand out like a proverbial sore thumb. This unruly cluster of practices happily dispensed with modernity’s heroes, the romantic picturesque and anaemic minimalism, while embracing exoticism and ornament, colour and surface, tourism and shopping, and, yes, the gloriously bad taste of the defiantly superficial, yet perpetually popular suburbs.

– Andrew Mackenzie is an architecture writer for the Australian Financial Review and a Director of Uro Publications and the architectural consultancy Citylab. He is the former editor of Architecture Review Australia.