The new “university in a building” of the Toni Areal, housed in a massive old milk factory in Zurich, is designed to bring new life to an area of this Swiss metropole that is in danger of becoming a mono-culture of gentrification. But Sasha Cisar questions whether it is integrated enough into the city fabric to really make a difference.

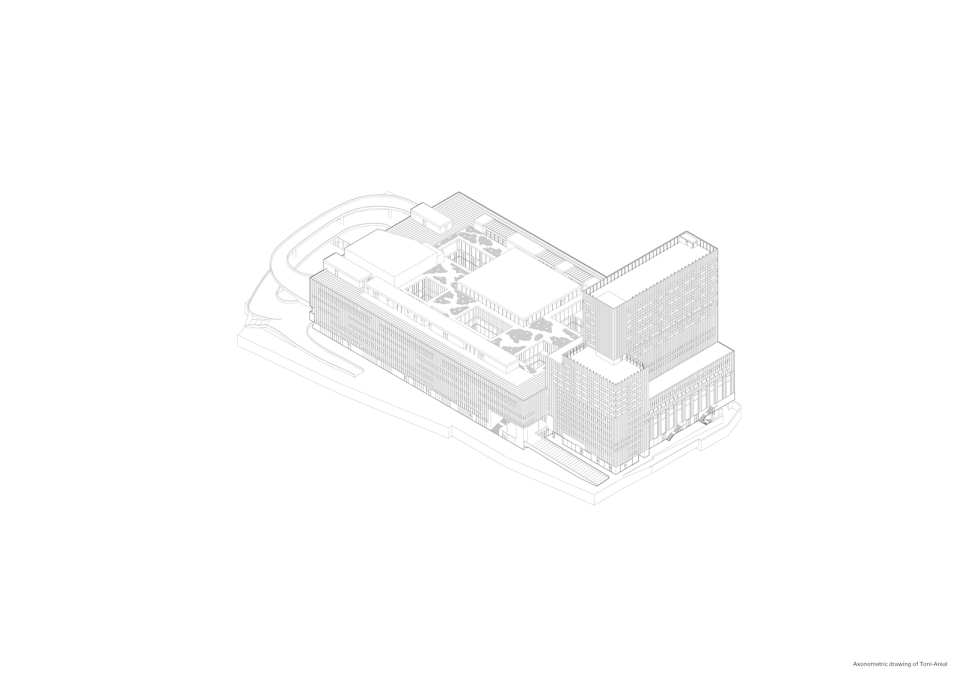

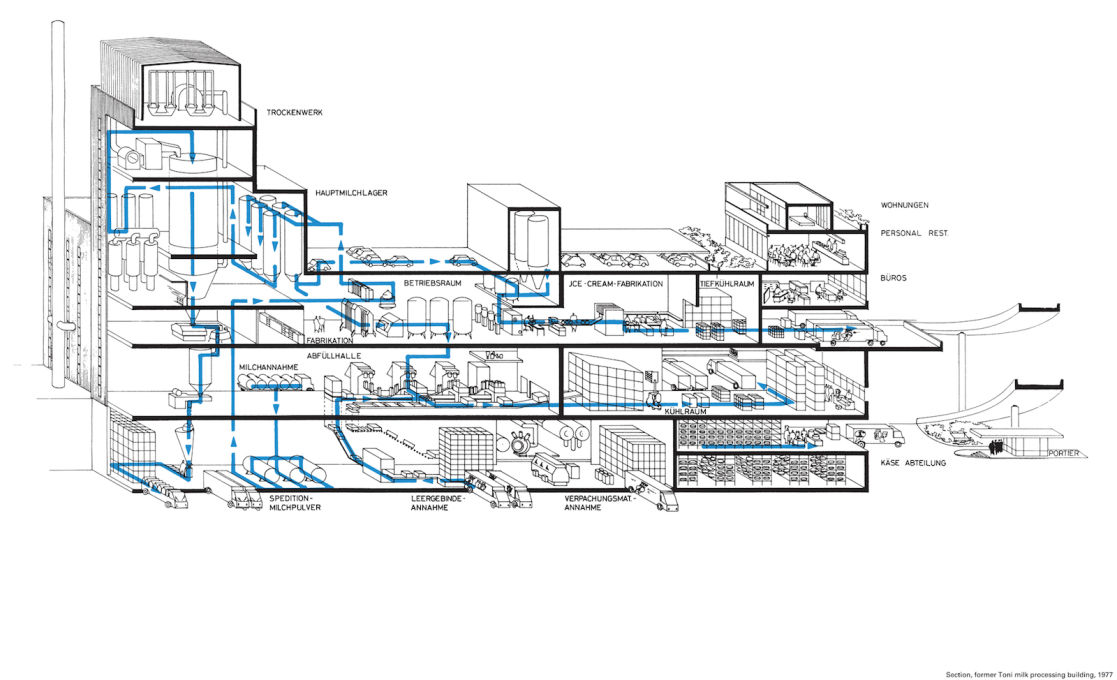

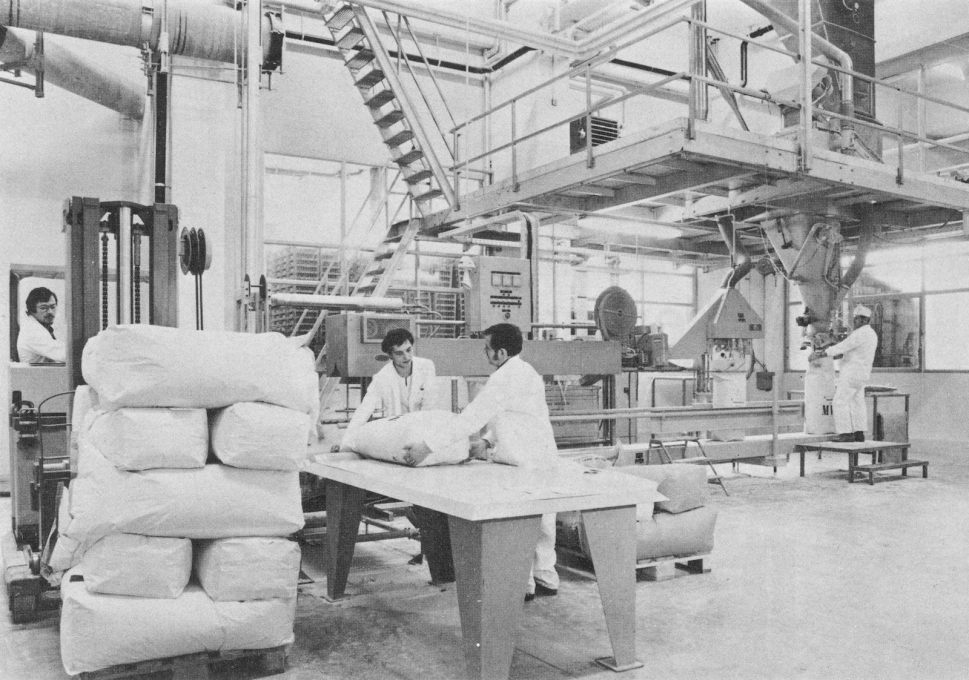

Can a building create a microcosm of the cultural diversity and creativity of the city that surrounds it, whilst critically engaging with it? This seems a relevant question in assessing the new Toni Areal complex in Zurich, which hosts an international campus of 3600 students and 1650 staff in a single building. Recently opened to accommodate and consolidate Zurich University of the Arts (ZHdK) and two departments of the Zürich University of Applied Sciences (ZHAW), it is housed in the former home of Europe’s largest milk processing plant, which belonged to dairy giant Toni, hence the name for the building complex, which occupies an entire city block. EM2N who won the competition to convert and design Toni Areal, collaborated early on with the Canton of Zurich, which was interested in finding a central location for two of its three cantonal universities, consolidating previously diffuse campuses spread across the urban fabric of the city of Zurich into one massive building.

Contrary to the Anglo-Saxon model, Switzerland hasn’t a particular tradition of university campuses that include student facilities from learning spaces to accommodation. Swiss universities were generally part of the urban fabric – take the main building of the ETH Zurich by Gottfried Semper, which forms a key extension to the medieval city centre. However, a shift in thinking occurred between the 1950s and 1970s due to modernism, with universities seeking to accommodate an increased influx of new students through creating quasi-campuses on green-field sites in proximity but peripheral to cities, outside the confines of the urban fabric of city centres. In Zurich, the University of Zurich (UZH) with its Irchel-Campus, and ETH Zurich (ETHZ) with the Hönggerberg-Campus, are both testament to this development, as are the ETH Lausanne (EPFL) and University of Lausanne (UNIL) – although today the latter two’s main campus sites have moved entirely outside Lausanne. But in all these cases, student housing was not provided on the campus sites, but remained dispersed throughout the city.

Therefore the concept of a campus combining all aspects of student life, surrounding a central yard (campus) in which students could meet and socialise throughout the day and into the evening, never existed in any specific form in Switzerland. And the concept of a central yard itself, where students and researchers could meet and informally exchange ideas, both within disciplines and interdisciplinary, was always entirely internalised into the buildings themselves. Even recently, the Rolex Learning Center at the EPFL embodied precisely this internalised idea of a yard. Its design by SANAA is only around 30% programmed in terms of function – as library, lecture hall or canteen – with the majority of the building left an undulated learning landscape to be appropriated by students as they see fit: to study, talk, socialise.

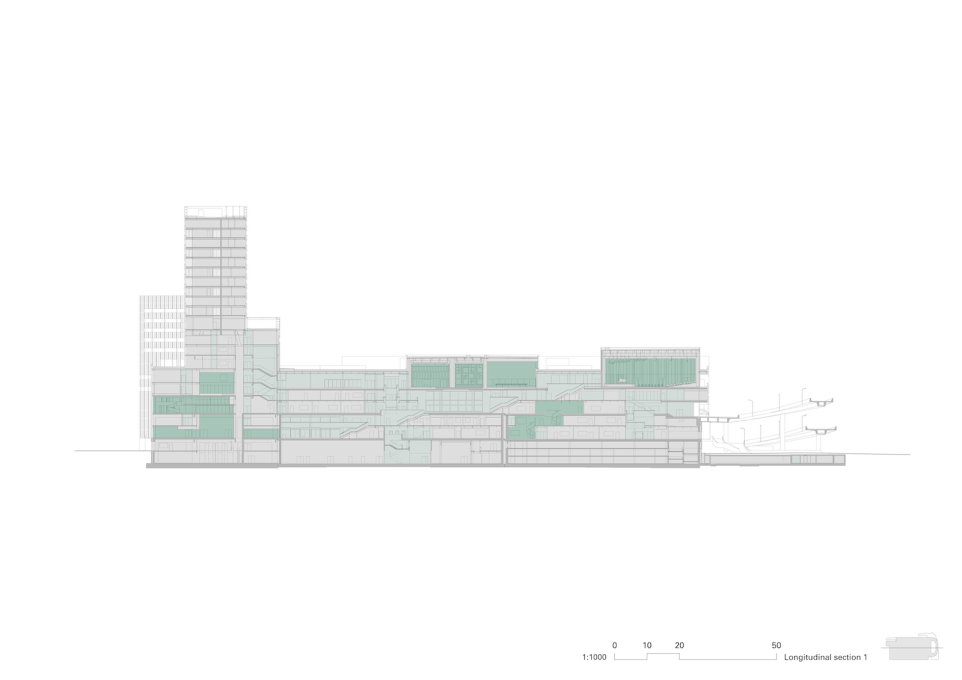

This generosity of gesture at the EPFL would be impossible at Toni Areal, given the need to combine an entire university (or two!) into one single, if huge, building. But this element of interface space is at the core of its design too, dictating the spatial organisation and circulation. A vast sequence of stairs rises from the lobby, dividing the two universities, and ascending through the massive base of the building towards the roof terrace. This feature of internal circulation not only expands vertically but also horizontally, allowing for this space of appropriation by the students. And these spaces have been left purposefully raw, aiming to encourage attack on the building fabric by art installations, stagings and performances.

Above, the stairs either meet a lavish urban rooftop garden or the spiralling ramps designed originally for the collection and delivery of dairy products, and also leading to the former car park. Ironically these ramps and the smooth metal mesh that uniformly clads the entire building are the sole reminders of the building’s industrial past. While the ramps would provide a visible expression of the internal accessibility and learning landscape, this is hidden by the cladding, which together with the vast size of the building, decreases its potential interface with its surroundings. So whilst entrances are placed strategically to correspond to the internal circulation, this still leaves hundreds of metres of inaccessible façade in between, with no programmatic activation to the outside world.

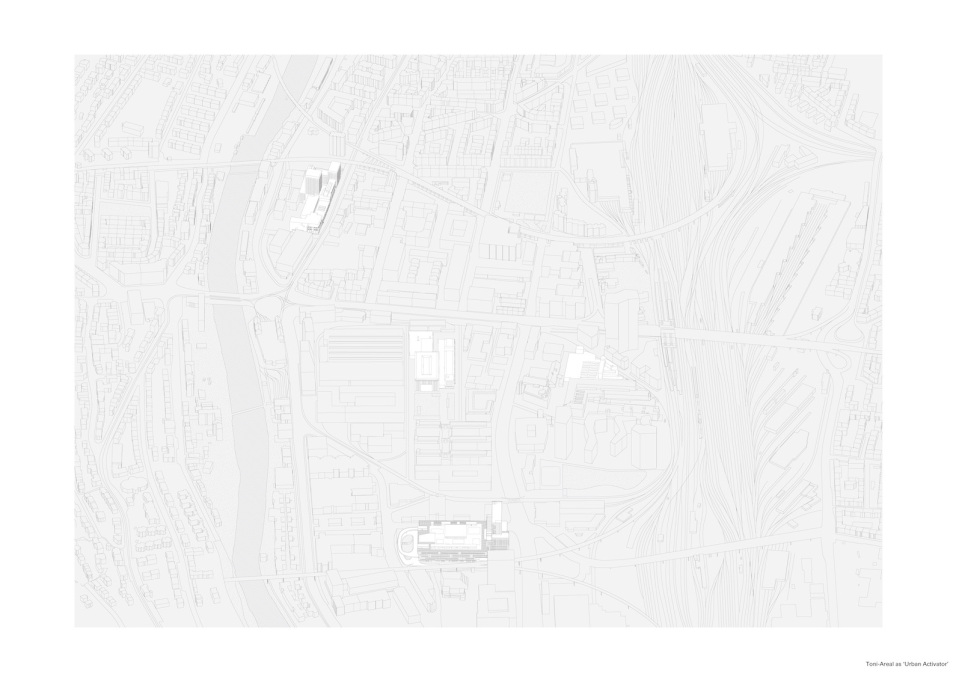

The Toni Areal is a culmination of a massive urban redevelopment of Zurich, paralleling an economic shift from the secondary to the tertiary sector, in particular in Zurich-Nord and Zurich-West, urban areas that had been mostly abandoned by manufacturing industry by the late 1980s, which had moved to the periphery of the city or abroad, leaving huge areas of inner-city urban potential by the early 1990s. The large-scale buildings that remained offered readily available, cheap space and accommodation, becoming temporary homes for artists and what Richard Florida calls the “creative core”. But the city of Zurich had its own particular way to treat this industrial heritage. In Zürich-Nord studies, plans and competitions mostly led to the razing of the existing structures and replacement of them with offices and housing. Meanwhile Zurich-West saw a more piecemeal transition of urban experimentation, with early mixed-use structures developing or the replacement of large factories with similarly large housing blocks or techno-parks, eventually resulting in an area that acted like a valve for the city, allowing for new large-scale and high-rise development like Gigon & Guyer’s Prime Tower (offices) and the Mobimo Tower (a high-end residential building and hotel) designed by Diener & Diener. While these are large-scale mono-functional buildings, recent developments show a return to more mixed-use structures, that try to incorporate the existing buildings and expand them where necessary. The large-scale envelopes of industrial buildings and structures in general were kept because they seemed to be attractive to investors for redevelopment. The transformation of the area with housing and offices, and its integration into the city centre, still therefore displays a shift in the texture of the urban fabric and its urban intensity. But the residential towers, signify urban densification rather than just mere vessels for developers creating expensive high-end lairs for the mobile 1% of Global City Zurich.

Thirty years ago Zurich-West with its large urban potential, was the breeding ground for novel housing experiments, with swathes of urban pioneers occupying structures left behind after the industry disintegrated. But what happened can be best described in German: Verstädterung statt Urbanität: the urban intensity decreased even as the building mass increased. The middle class and the wealthy moved in, into expansive – and expensive – apartments, and despite some continuing contradictions, Zurich-West became one large gentrification project.

The difficult condition of this context goes to explain the involvement of the Canton and City of Zurich, working with the universities and architects, in formulating what is a highly programmatically charged, mixed-use building, which will hopefully provide a spill-over effect, through its students’ influence on the surrounding area. For what originally created and defined the transformational character of Zurich-West was here internalised, with the “Toni Areal”, a public, cultural and private hybrid – with educational and creative uses in its base and a residential tower above. So though the Toni Areal is part of and supports the urban processes of redevelopment, it also presents the potential to counteract them. However the increased complexity and hybridity of programming it brings is undermined by these factors of scale and lack of accessibility.

On October 25, 2014, the ZHdK organised a celebration of their new Toni Areal coincidently entitled “Creative City”. This was organised into “neighbourhoods“, each reflecting a different artform, tested as a Kreativer Ausnahmezustand – or “Creative State of Emergency”. If only such a state of emergency could manifest real creative and urban intensity: for the question remains whether the “Toni Areal” and its art students, can really become the intended catalyst to ameliorate the urban development of this area of the city, and curb the influence of investors. I have my doubts.

– Sasha Cisar is an architect and theorist, currently researching zero-emission retrofits of buildings at ETH Zurich. He co-founded and edits a journal on architectural theory called "Models Ruins Power" and recently published its first issue: “We Live In Models”.