A little south of Cologne in an utterly unremarkable residential area, curator and uncube author Oliver Elser discovered a small brick building hiding in the bushes. It is Haus Nagel, designed in 1966 by German architect Heinz Bienefeld (1926-1995), one of the most uncelebrated yet remarkable architects of post-war Germany. The building’s inconspicuous outer skin contrasts with the rich and loving details that unfold both inside and in the walled garden. It’s a postmodern jewel which, according to Elser, could have had it’s role in architectural history and place in the sun, if only Charles Jencks had known about it before chronicling the rise of postmodern architecture...

On July 21, 1969, the same day the first man set foot on the moon, Mr and Mrs Nagel moved into their new house. It was a strange coincidence. While most people that day celebrated the dawn of a new future filled with space capsules, computers and high-tech materials, in Cologne, this small counter-utopia against technological progress had been erected that chose to look back to history: Andrea Palladio instead of Apollo 11, bricks instead of steel, handicraft instead of robots.

Architect Heinz Bienefeld, who was 43 years old at the time, found the ideal clients in the jeweller Wilhelm Nagel and his wife, creating for them, together with artist and artisan friends of his, a completely anachronistic house. Had Charles Jencks known about this in 1977, when he trumpeted the arrival of postmodern architecture, then Heinz Bienefeld might now be placed on par with Robert Venturi, who, with the modest Vanna Venturi House (1964) that he designed for his mother, counts as one of the founding fathers of postmodern architecture. But Jencks wrote the history of postmodernism with the works of Charles Moore, Aldo Rossi and James Stirling, although no one at the time was very pleased with the label “postmodern”. None of those architects ever wanted to be considered as such, and Heinz Bienefeld would later also scowl in disgust when he was referred to as Germany’s first postmodernist.

When Bienefeld made his initial sketches in 1966, he could thus not have known that he was part of a larger global movement of architects beginning to rattle the staleness of post-war modernism, and falling back so strongly back onto architectural history that we are still reeling from the effects it today. Bienefeld was a loner, an outsider, who could remain silent and brooding throughout an entire evening, even when in company and being praised for his uncompromising buildings. Following his studies, from 1955 to 1962 Bienefeld worked for other “outsiders” or lone wolves of German architecture, be they very different architects from him, such as Dominikus Böhm (1880-1955) and his son Gottfried (born 1920), known for their churches, or Emil Steffann (1899-1968). After working on his own, on extensions, renovations and a new-build church, Haus Nagel was his first single-family house.

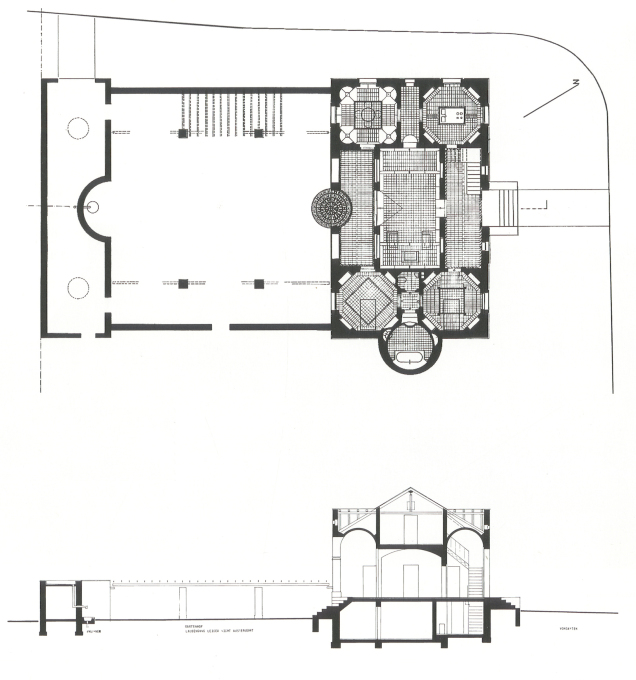

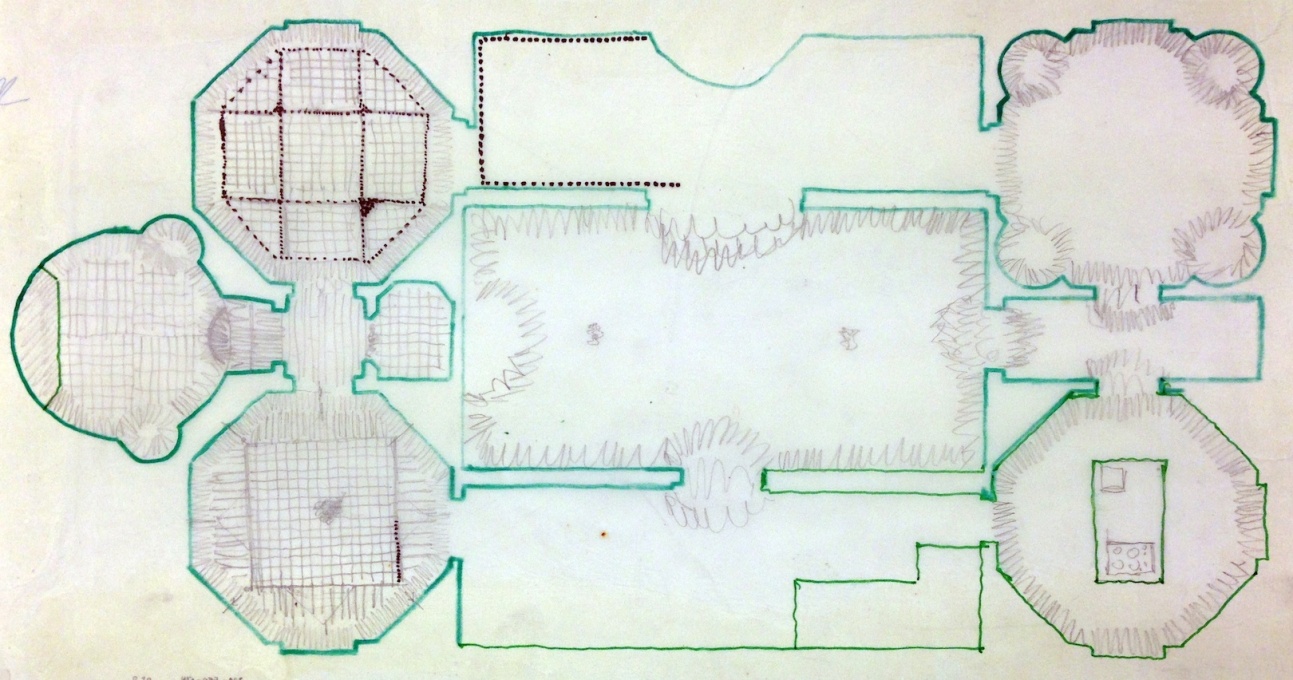

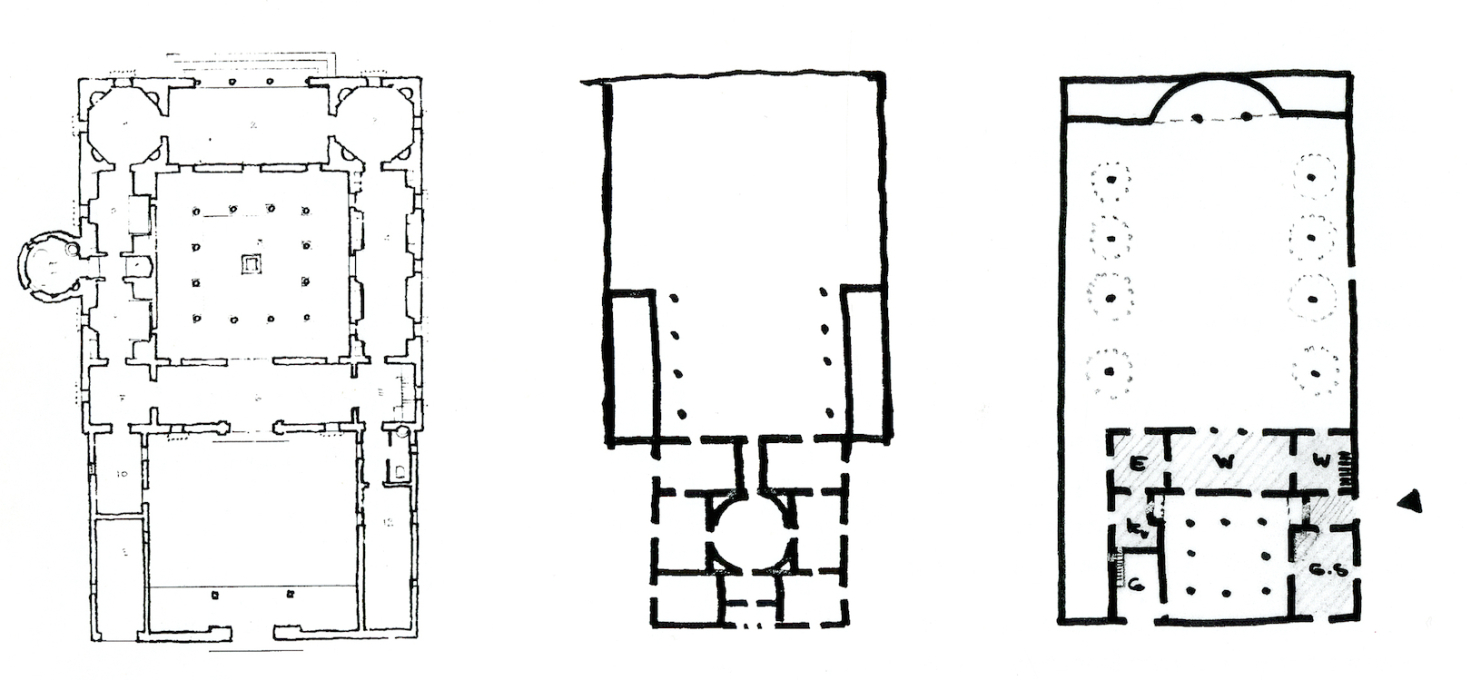

The house, located in an otherwise typical residential area of detached houses to the south of Cologne, seemed for decades to be so far removed from its surroundings and the times, that neighbours had a running gag of ringing the doorbell and asking for the vicar. Indeed, Bienefeld did not want the house to have anything to do with its banal location. Early plans depict an even more drastically introverted design: an atrium house focused solely on an internal courtyard. Bienefeld ultimately developed the courtyard into a garden, which is surrounded by walls so high that the surrounding neighbourhood remains invisible. Bienefeld’s mentors were Nature, Antiquity and the Renaissance.

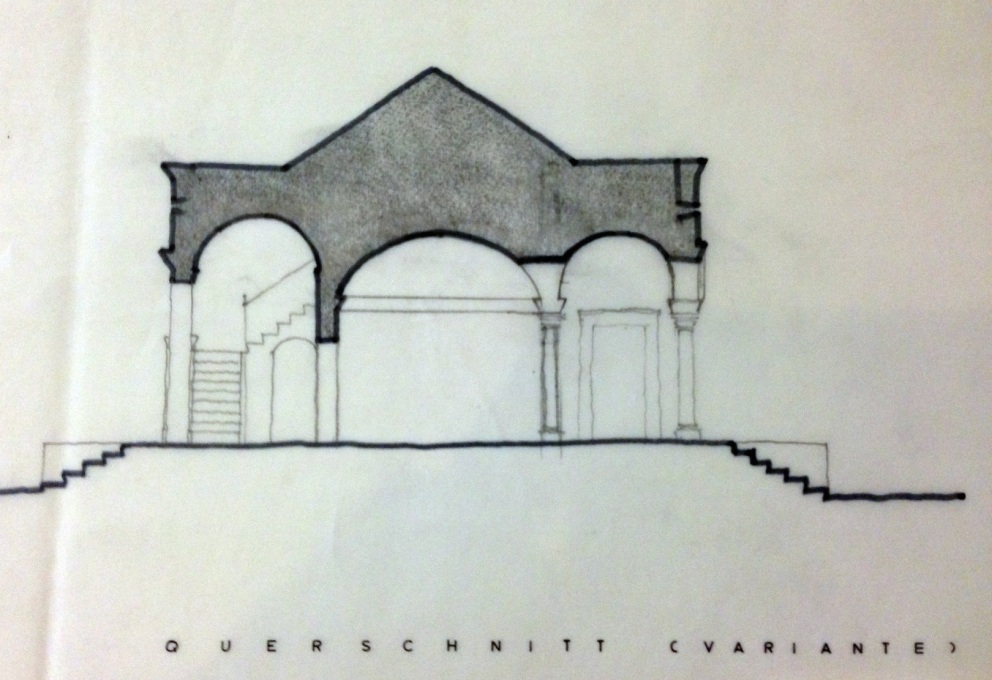

The little brick house receives its visitors with a grand gesture: the arched portal with its triangular gable, reveals his fascination with the Renaissance villas that Andrea Palladio created for wealthy Venetian families. But first impressions are deceptive: the building’s interior is much smaller than expected, albeit no less refined than Palladio’s, in regard to its spatial proportions. Lurking behind the plain, rough brick masonry of the entrance façade are the unexpected pleasures of rich detail and alluring surface. One’s eyes and hands want to glide endlessly across the elaborately finished materials, many of which are surprisingly commonplace and inexpensive. For example, Bienefeld found the terracotta floor tiles as remaindered stock at a construction materials store. But he laid them with marble tiles into ornate carpet-like designs, allowing some of the tiles to show the studs and grooves of their underbellies to create unexpected patterns. The walls are plastered to create a play of light and texture even along straight white walls. Built-in closets have translucent doors of finely polished alabaster. The ceilings are flat cross-vaults, intersecting one another. But the bathroom is the biggest surprise: a circular space, laid out like the apse of a church, with steps leading up to it like in an ancient thermal bath.

Artist friends executed many of the details. They knew one another from the Cologne Werkschule (Art and Design Academy), where both Bienefeld, as well as his client Wilhelm Nagel, were lecturers. The wrought iron work was done by the jeweller’s brother, Paul Nagel; the stained glass windows with polished agate stones were made by Heinz Bischoff; the cheeky Medusa sculpture, stretching her bare bottom into the living room, was by Theo Heiermann. Titus Reinartz crafted a marble snail at the entrance and was also responsible for the most charming artwork in the house: atop four brick columns in the garden, which were originally designed to support the atrium roof, he perched sensually swelling oversized vegetables cast in concrete: fennel, eggplant and capsicum.

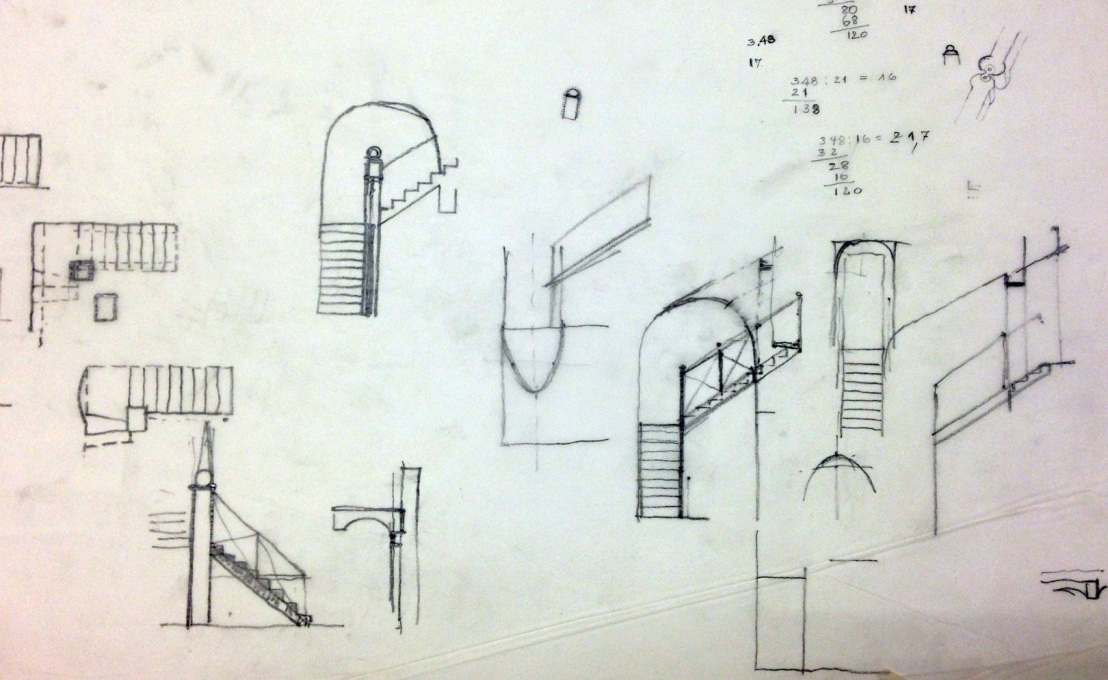

The stairs to the garden have become one of the most famous motifs in Bienefeld’s work. A brick staircase in convex-concave circles leads down from a classic three-part arch of that sort that Palladio popularised: a so-called “Serliana” after its originator Sebastiano Serlio, which is flanked by two additional columns and two window openings. Of course, Bienefeld’s columns also have capitals: not carved from stone, but built in brick. Yet Bienefeld was also a master in bringing “cheap” materials to the construction site and extracting the best performances from his craftsmen in order to refine them, like the white metal supports in the living room’s glass façade which he got for free as they were parts of a demantled rail track!

The house has remained in the possession of the Nagel family since 1969, but Wilhelm Nagel’s widow sees its sale as increasingly probable. Haus Nagel holds a special place in Bienefeld’s oeuvre: never again would he base his buildings so closely on historical models. He went on to interpret the teachings of architectural history with increasing abstraction – even if he never quite lost his fascination for atriums, massive brick walls and masonry pillars.

Bienefeld’s legacy is catalogued at the Deutsches Architekturmuseum (DAM) in Frankfurt as a permanent loan, and is a veritable treasure trove: such an inventive architecture is only possible due to the hundreds, if not thousands, of plans and sketches that Bienefeld prepared for each of his projects – mostly drawn by himself. Until his unexpected death in 1995 he had created some 40 residential buildings, a few churches and a childcare centre. Bienefeld’s work is universal, positioning itself in the continuity of architectural history – yet maintains a spirit that is as independent and distinctive as any seen in German architecture since 1960.

-- Oliver Elser is a curator at the Deutsches Architekturmuseum (DAM) in Frankfurt, a writer and an architecture critic for various European magazines and newspapers. His last exhibition at the DAM was called “Mission Postmodern”, dedicated to the museum’s legendary founding father, Heinrich Klotz. See our interview with Elser on the background to the exhibition.