While it might seem like you’re DIY-ing it when you assemble your IKEA bookshelf, there’s actually very little experimentation involved in the process. That’s why the website IKEAhackers has become so overwhelmingly popular: it provides a platform for consumers to truly customise the standard products. Yet, as Peter Maxwell writes in this essay, a recent face-off between the company and the website presented IKEA with a choice: to sue or to swallow the semi-subversive movement.

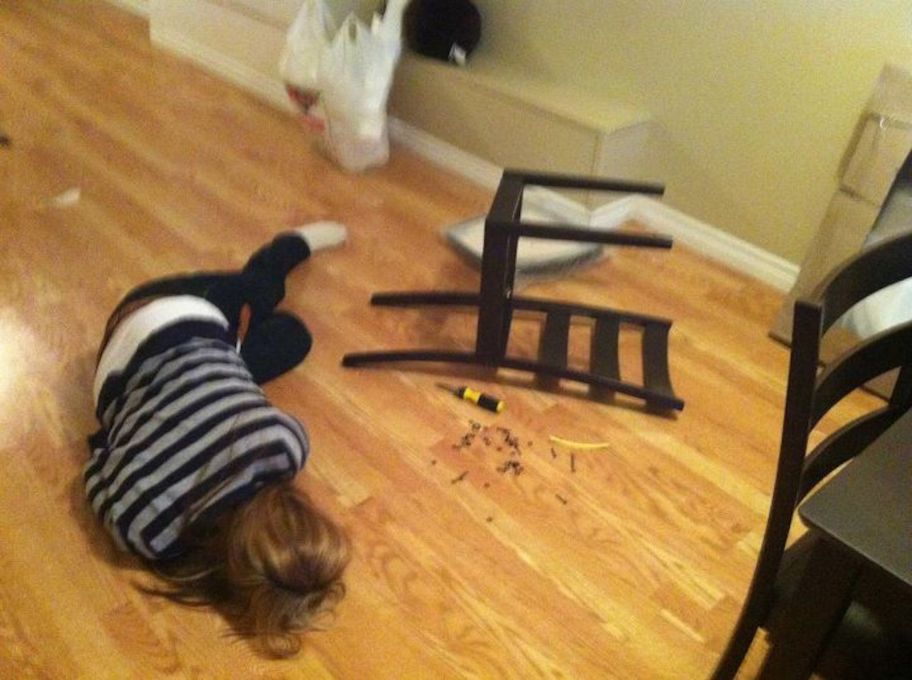

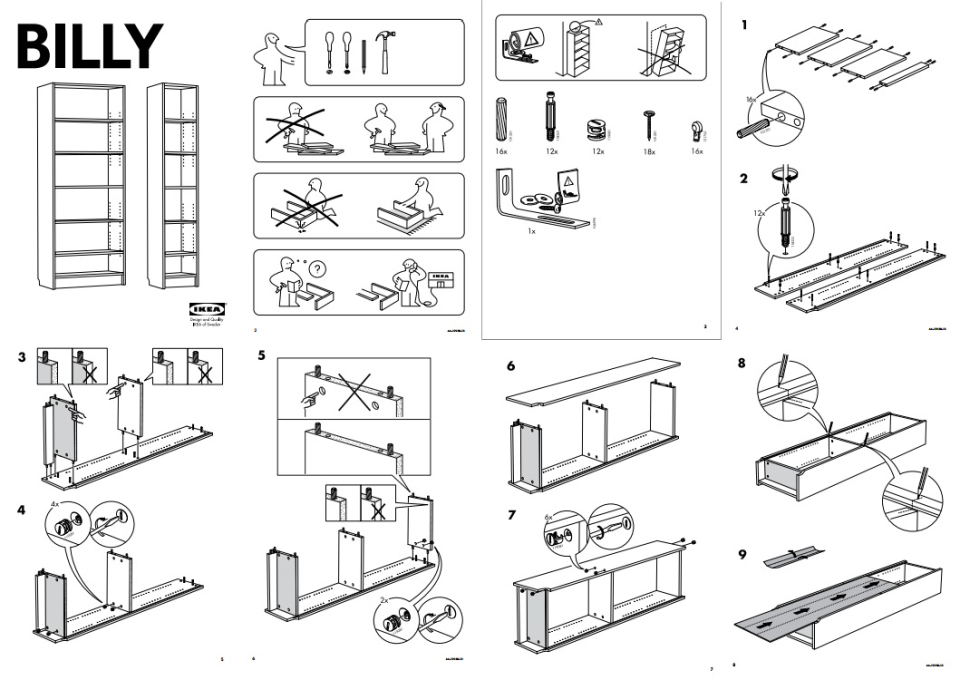

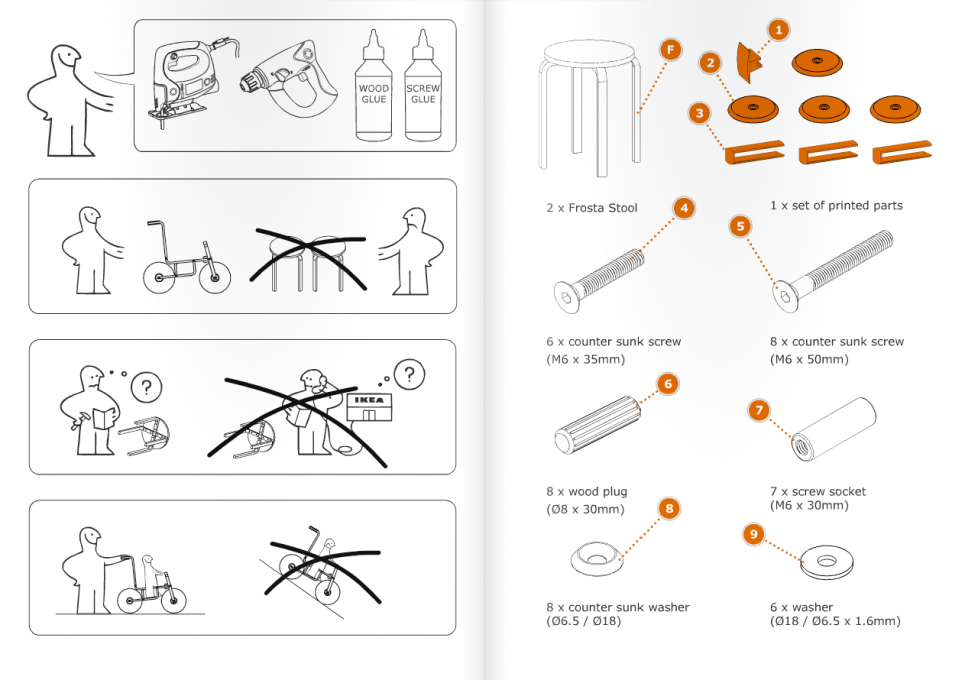

When Jules Yap established her website IKEAhackers eight years ago, it was out of affection for the brand and its wares, but also the belief that its products could be adjusted to fit us all somewhat better. The site is a portal for people to share instructions for original pieces of furniture created from components taken from various IKEA products. These tend towards the functionally pragmatic, contortions of mass-manufactured furniture that fit the specific demands of domestic spaces: storage beds jerry-rigged out of chests of drawers, or bookcases recast as work desks. The official names of certain products reappear – Frosta, Faktum, Expedit, Billy – celebrated not only for their intended morphology or use value but the plasticity of their parts.

Over its lifetime the site has grown into a community of IKEA obsessives. With growth comes increased maintenance, however, and the burgeoning traffic meant that Yap had to begin selling advertising space to cover the costs of what remained a hobby. At this point IKEA, having been silent on the matter for almost a decade, stepped in, issuing Yap with a “Cease and Desist” order due to her use of the IKEA name.

Yap was understanding about the corporation’s right to protect its trademark as it sees fit, but not its heavy-handed approach (she is, as she notes, merely a blogger). After the inevitable backlash from supporters of the site (and, by extension, IKEA customers) the company released a missive asking its patrons to “trust” their brand: “When other companies use the IKEA name for economic gain, it creates confusion and rights are lost.”

There are cogent reasons for the company to act censoriously: objects that are identifiably of the brand but that don’t meet its internal design standards, in terms of look, operation or safety, may leave consumers with an unfavourable impression. But what remains perplexing is IKEA’s motivation and timing for sending the letter. While the use of the IKEA mark could arguably cause confusion, that was true since IKEAhackers’ inauguration; there is no logical reason why unassociated advertising on the site would heighten that misdirection. In fact, as the anti-copyright activist and blogger Cory Doctorow attests: “IKEA’s C&D is, as a matter of law, steaming bullshit…There is no chance of confusion or dilution from IKEAhackers' use of the mark. This is pure bullying, an attempt at censorship.”

As it’s hard to see how Yap’s project might affect the corporation’s bottom-line, this must be considered a symbolic battle. Unhappy that its products’ facility was being called into question, but hesitant to prohibit an entity championed by its customers, apparently IKEA instead sought to sanction the website’s existence whilst removing its support structure, waiting for the site’s success to provide the mechanism for its downfall. Here, like Yap, IKEA is a victim of its own accomplishments. When it began producing flat-pack furniture in the mid-1950s, the economic benefits due to reduced labour, transportation and storage costs were the driver. The reuse of parts, joints and proportions refined this system further. But while these efficiencies might have proved an effective business model, as it turns out they also offer the opportunity for people to construct the company’s furniture in unauthorised ways, its combination of ubiquity and plasticity meaning that it can’t be fully controlled. What IKEA has created is a grownup toy box from which adults can craft their domestic idylls beyond company guidelines.

IKEA’s products have developed out of a basic interpretation of modernist design principles and its marketing is heavily based on the associated attributes of health, happiness, honesty and moral integrity. Its otherwise fruitful monetisation of modernism hides a dilemma, however – the myth of functionalism in a truly commercial context is that needs can’t be so widely generalised, and therefore addressed with entirely appropriate design solutions. Thus we arrive at the oxymoronic situation in which a supposed (albeit watered down) version of functionalism actually results in the sort of obsolescence that enrobes the planet in junk. IKEA was undoubtedly complicit in this, until some of its customers realised that what the firm actually produced was a set of fairly standardised parts quite amenable to disobeying the rules set down by its accompanying schematics.

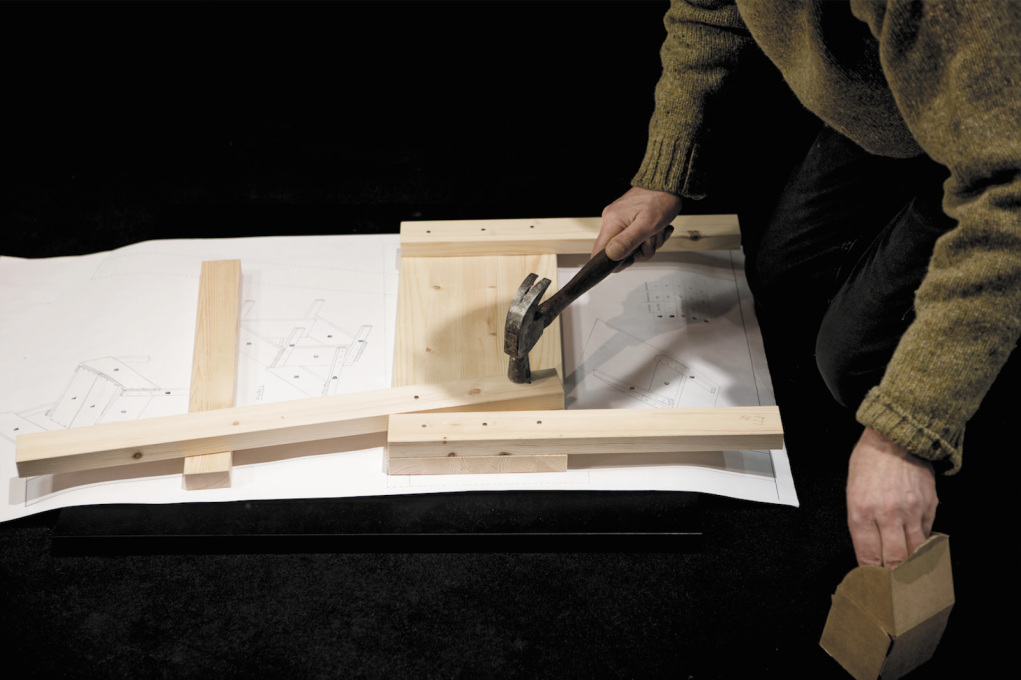

Italian designer Enzo Mari’s Proposta per un Autoprogettazione (Proposal for an Auto-design) project from 1974 presented a semi-inversion of the model that IKEA has developed over time: write a request to Mari’s studio and he would send you a manual of instructions on how to erect his furniture from standard sized pieces of lumber and some nails. Mari explained his intention in 1983: “the designs have no measurements and while you are making them you can make changes, variations... when making the object the user becomes aware of the structural reasoning behind the object itself, therefore, subsequently he improves his own ability to assess the object on the market with a more critical eye.”

This notion of critical making is at the heart of IKEAhackers’ popularity, the site performing an embodied criticism of the IKEA range and its applicability to the lives of consumers. Andres Jaque Architects analysed the disconnect between the world’s largest furniture producer and its customers in the 2011 film study IKEA Disobedients, questioning the brand’s claim to service the social structures of the average contemporary home, rather than some normative image. In particular the filmmakers took issue with the company slogan “The independent republic of your home”, noting that public and private have long been interconnected.

Martin Enthed, IT manager for IKEA’s communications agency, disclosed earlier this year that 75 percent of the product shots now used in IKEA catalogues are computer-generated. This revelation only enhances the idea that the company trades on a useful fiction; if the nuclear family that inhabits the brand literature doesn’t already misrepresent its customers enough, that bubble of normativity is rigorously enforced, such as a case when an interview with a British lesbian couple was elided from a Russia edition of the 2013 catalogue, or when the company decided to remove all women from a 2012 Saudi Arabian iteration.

Given its principles of normativity, why use IKEA at all? Why not, extending Mari’s example, just do it for yourself? The critic Reyner Banham had a straightforward answer in the Royal College of Art’s student magazine, Ark, in 1969, responding to the customisation of hot-rods: “a situation like this enables you to concentrate on your areas of talent and get the rest done by experts. You can make up as much of an original life style as you want and conform where you feel the need.” Increased means don’t always mean increased desire or ability, and it is an unstated recognition of the professionalised designer’s proficiencies that users don’t start from scratch.

In the context of furniture, the idea of consumer as customiser was identified by the Dutch design firm Droog’s Design for Download presentation at the 2011 Salone del Mobile in Milan, the studio offering executable files for the CNC cutting and 3D printing of everything from tables to plug sockets. The apex of the project was Droog’s development of a suite of digital design tools that allowed ordinary computer users to make functional design decisions about their desired product. Extrapolating this idea into the space between IKEA and IKEAhackers, it isn’t unimaginable that the brand could someday relinquish its authority over its objects, relabeling them as kits of parts and developing the sort of interface to allow consumer to shape them more fully to their needs.

In his essay Is There Bauhaus in IKEA? (2009), published on Design Observer, writer David Barringer suggests that the company needs to be open to exactly that sort evolution if it is to survive: “A glut of cheap, uniform products in the marketplace can no longer be a virtue of global business. To pursue Bauhaus principles in the future, IKEA will have to increase the personalisation of its products, improve ergonomics, reduce wastefulness and increase quality in order to create lasting value for the consumer.”

As IKEAhackers has already proven, consumers can and will create that lasting value for themselves, regardless of brand sanctioning – it is up to companies like IKEA to decide whether they want to profit from their ingenuity or to merely continue to act the autocrat. And IKEA did eventually back off, after Yap received overwhelming support from the design press. The IKEAhackers site was allowed to remain in its current state IKEA invited Yap to Sweden, where she met Torbjörn Lööf, the CEO of Inter IKEA Systems B.V., for a conversation that she describes as “warm and honest”. There was even discussion of including an IKEAhacking section in the soon-to-be-built company museum at Älmhult. If this shows a willingness to recuperate this incident as part of IKEA’s history, the pressing question remains as whether it will be allowed impact its future.

- Peter Maxwell is a freelance design critic based in London. He is cofounder of design biennial Dirty Furniture and has written for such publications as Disegno, Art Review, Space, form, MARK and Grafik.

IKEA Disobedients is an architectural performance by Madrid-based Andrés Jaque Arquitectos that premiered at MoMA PS1 as part of the 9+1 Ways of Being Political exhibition. Watch the accompanying video here: