They might be the most significant modern masters in architecture that you have never heard of: with a current exhibition and comprehensive catalogue at MARTa Herford exploring their work, the brothers Rasch are ripe for rehabilitation into the modernist canon. And whatever the true influence of their ideas on others, two things are for certain – they produced some extraordinarily visionary drawings and had a genius for falling out with people.

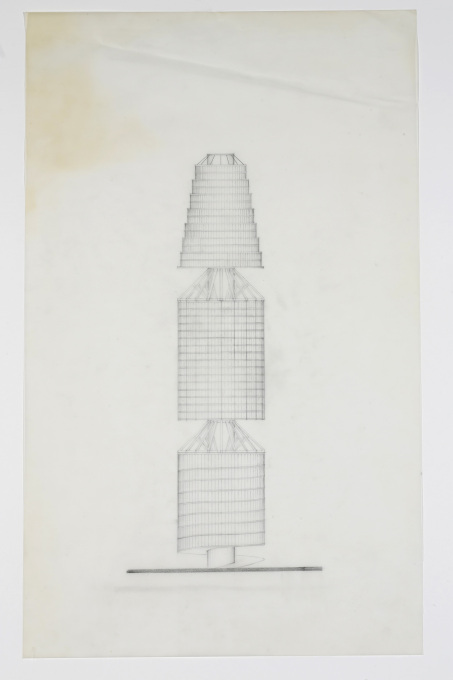

If you are interested in twentieth century architecture but have never heard of the German modernist architects Bodo and Heinz Rasch, there’s no reason to feel embarrassed. For despite their profusion of radical designs for high-rises, schools, theatres, stadia, houses and even entire towns – their work has remained largely unknown. Which is, as the current exhibition The Unfettered Gaze at the MARTa museum in Herford (Germany) proves, rather a large blind spot in the history of modern architecture.

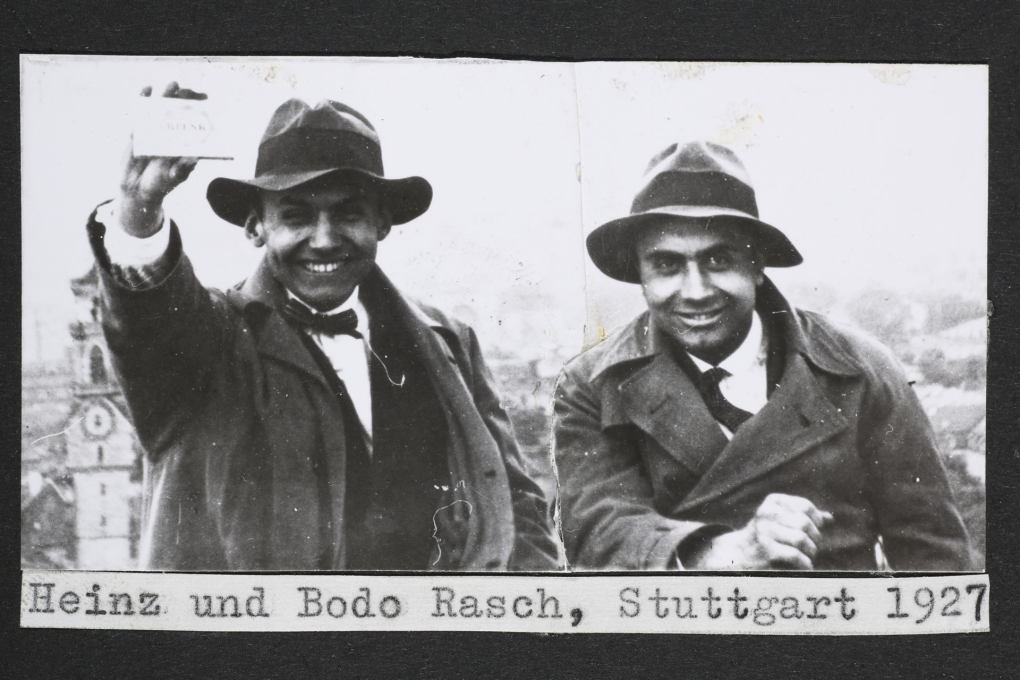

Brothers Heinz (1902-1996) and Bodo (1903-1995) Rasch only worked together for a short period of around four years. Elder brother Heinz, having set up his office while still studying at Stuttgart’s Technical University, was joined by Bodo in 1926, and until 1930 they would share a joint apartment and studio together, living and working almost in each others’ pockets. It was a remarkably productive period, and being excited about the radical new currents in art and architecture around them, the Rasch brothers enthusiastically picked up on the idea that all areas of design are interrelated: from architecture, urban planning and product design, to graphics, fashion, furniture and advertising.

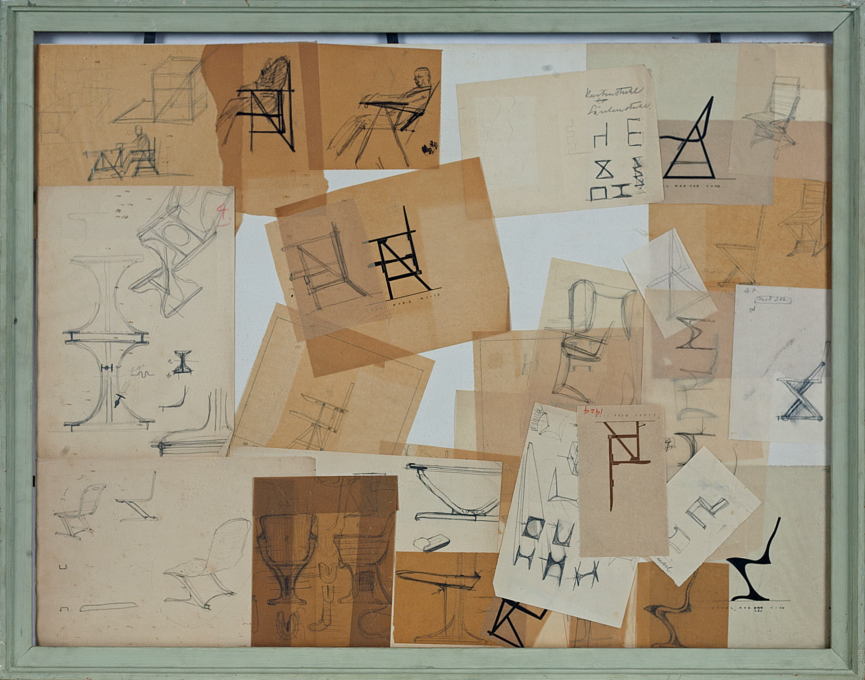

While they were kept busy in their office mostly designing fair stands, exhibitions and shop displays, the Raschs also published five books on fundamental questions of design. The exhibition title refers to their 1930 publication Der gefesselte Blick (“The Fettered Gaze”) focused on the “new advertisement art”, but previous books had included Wie Bauen? (“How to Build?”, 1928), Der Stuhl (“The Chair”, 1928) and Zu-Offen (“Closed/Open”, 1930), with each a mixture of manifesto and analysis, typical of their time, seemingly inspired both by Le Corbusier’s publishing strategy and the contemporary revolutionary manifestos of the Bauhaus.

Their “studio-laboratory” quickly grew into Stuttgart’s hotspot for any visiting modernists to the city. From Heinz Rasch’s letters we learn that the brothers were not only friends with artists like Oskar Schlemmer, Kurt Schwitters and Otto Dix, but also in contact with architects like Walter Gropius, Erich Mendelsohn, Bruno Taut, Mart Stam and Mies van der Rohe, the latter being a “splendid person and pleasant guest”, as Heinz wrote to his fiancé Jutta Kochanowski in 1927. “He felt very comfortable here and also wrote to thank us for the time.”

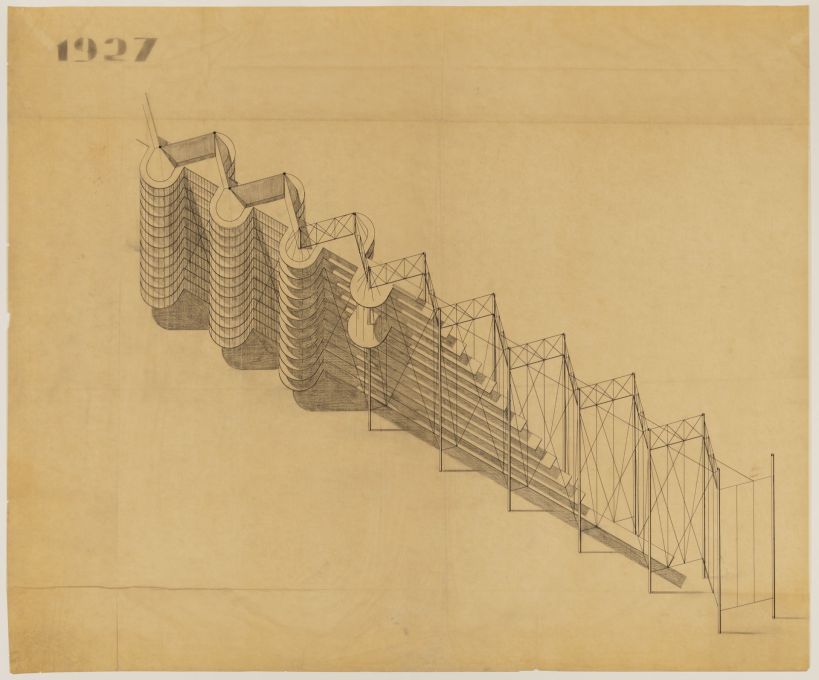

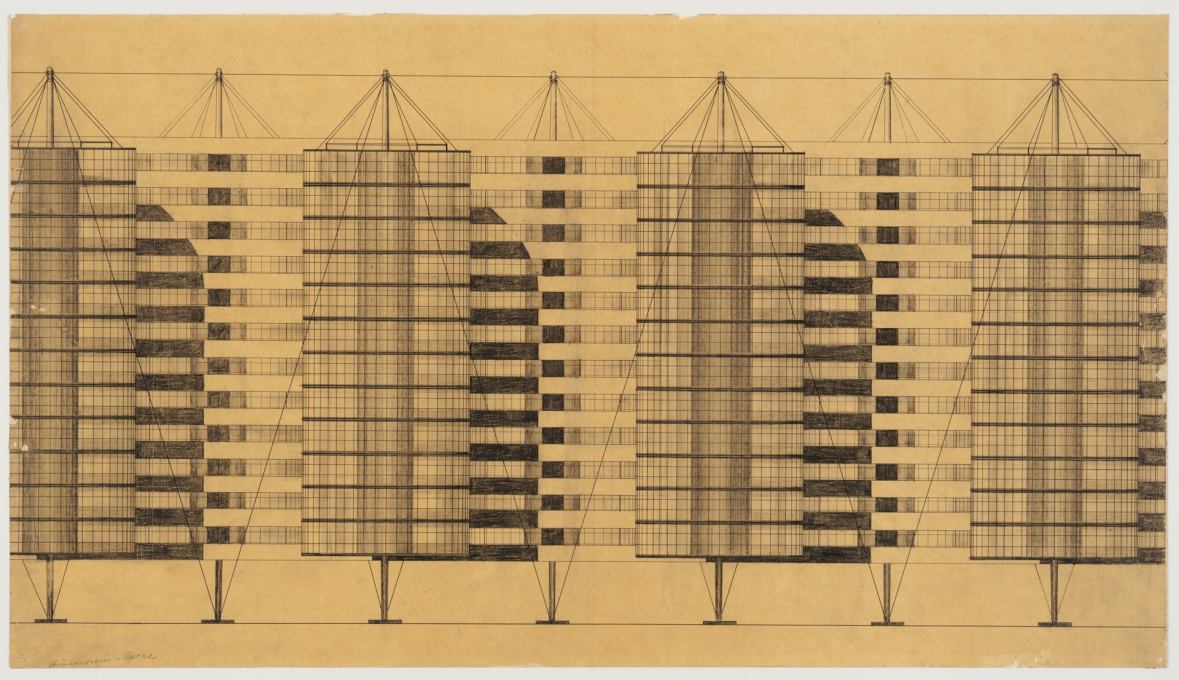

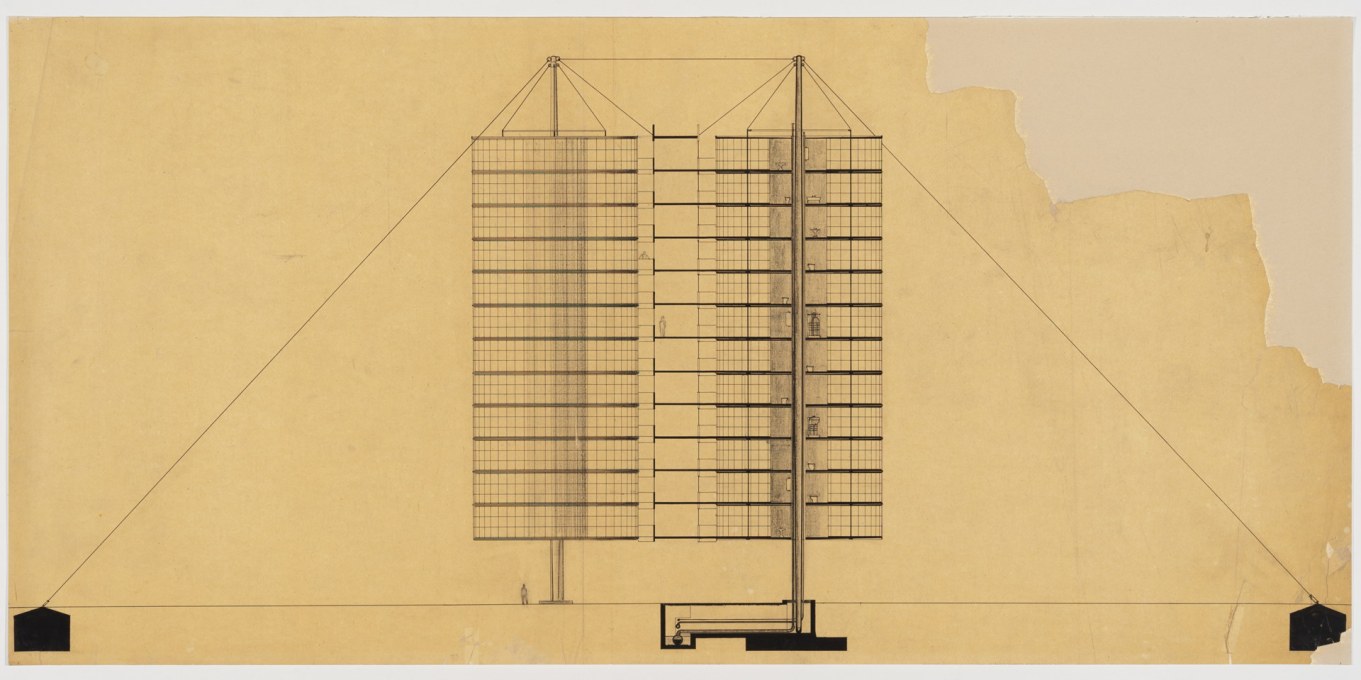

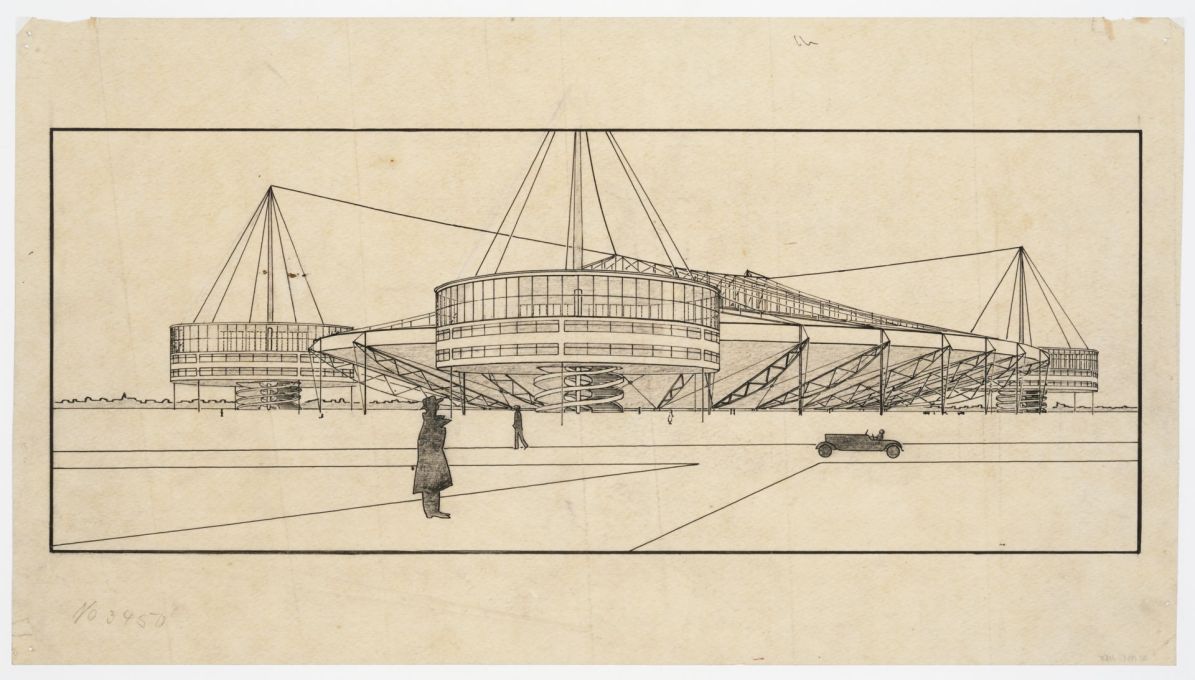

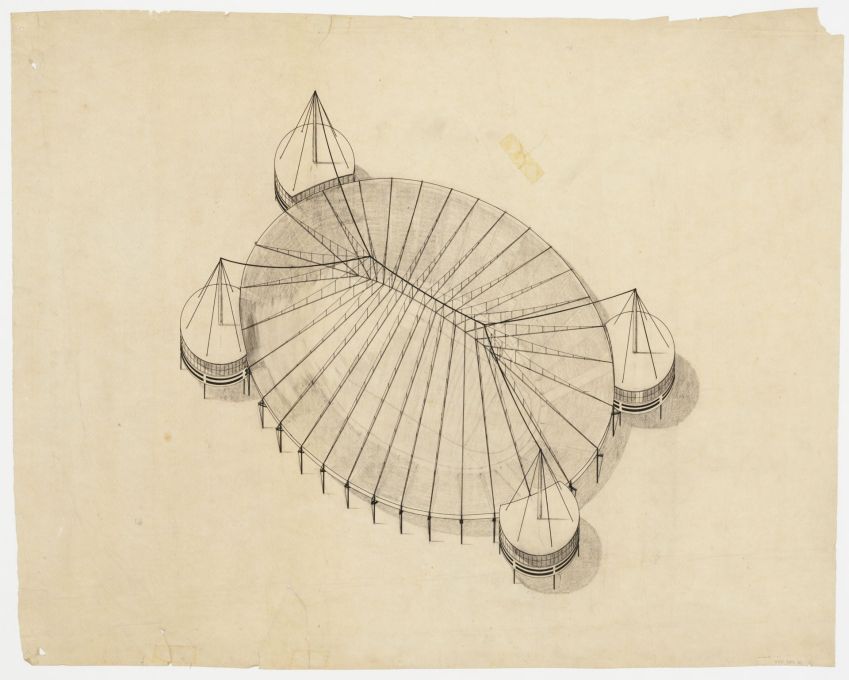

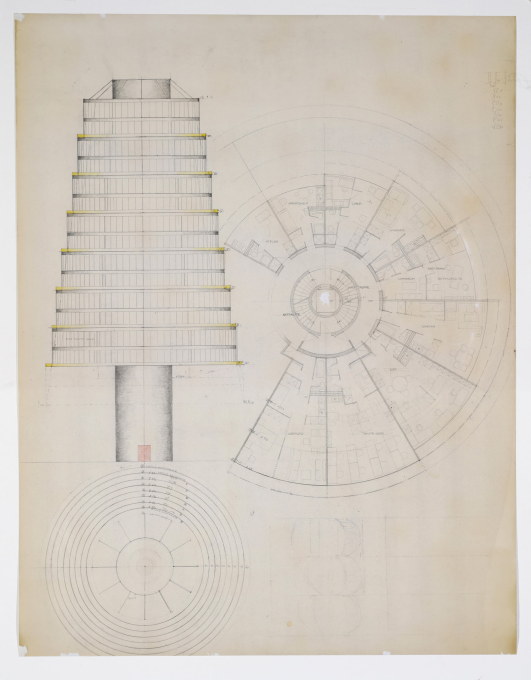

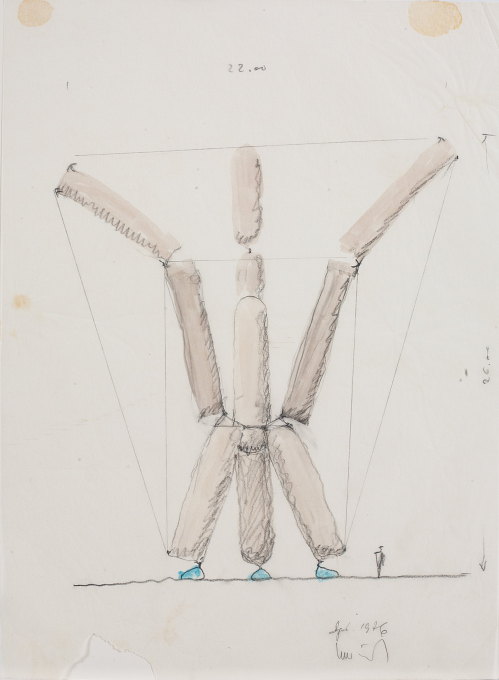

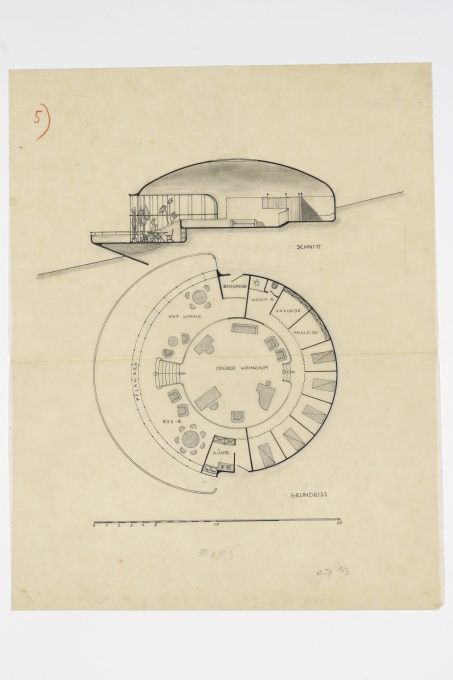

Being so closely connected to many of the most important protagonists of different modern art movements, the Raschs experimented with light-weight, pneumatic and suspended construction techniques for furniture and for buildings. Yet their experiments for the most part remained on the drawing board. However they were invited to design the interiors of three apartments at Stuttgart’s Weißenhofsiedlung (supervised by Mies van der Rohe and completed in 1927), which could have been their big break, but typically for them the opportunity went pear-shaped. Apparently Mies van der Rohe didn’t like the plywood furniture they constructed for their “Apartment for a Batchelor” – perhaps because Mies was himself doing similar plywood furniture at that time, or perhaps because the details of the Raschs’ furniture were indeed a bit clottish.

Later, when Mies patented his famous cantilevered chair, Heinz wanted him to admit that the design was based on the Raschs own cantilevered chair design – which Mies refused to do. Indeed the Rasch brothers seem to have had a genius for gradually falling out with their peers. For in the years following, trying to protect many of their drawings and ideas as their own copyright, they also argued with Buckminster Fuller over the original inspiration behind the suspended construction of his famous “Dymaxion House”.

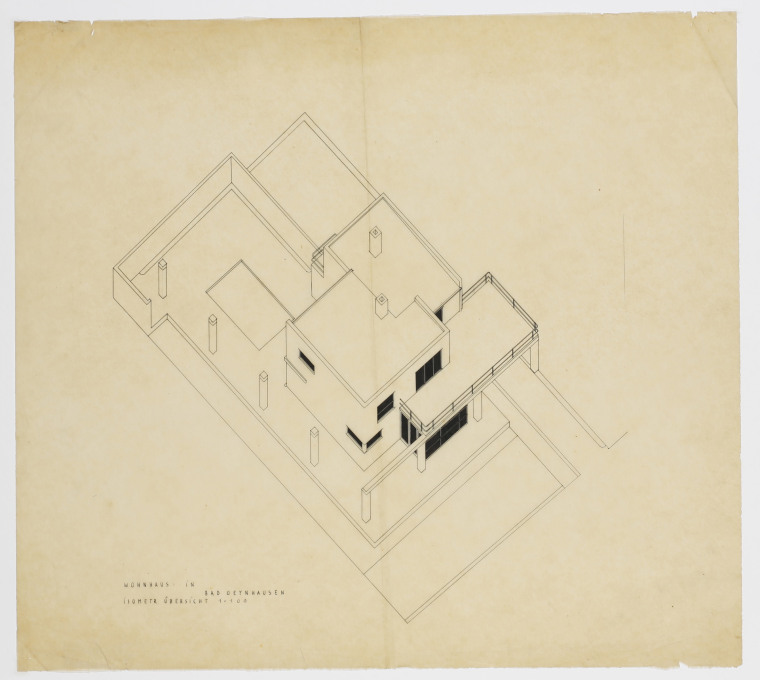

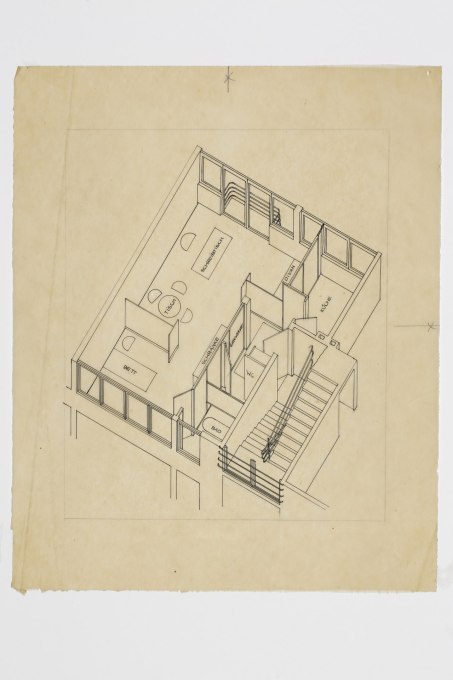

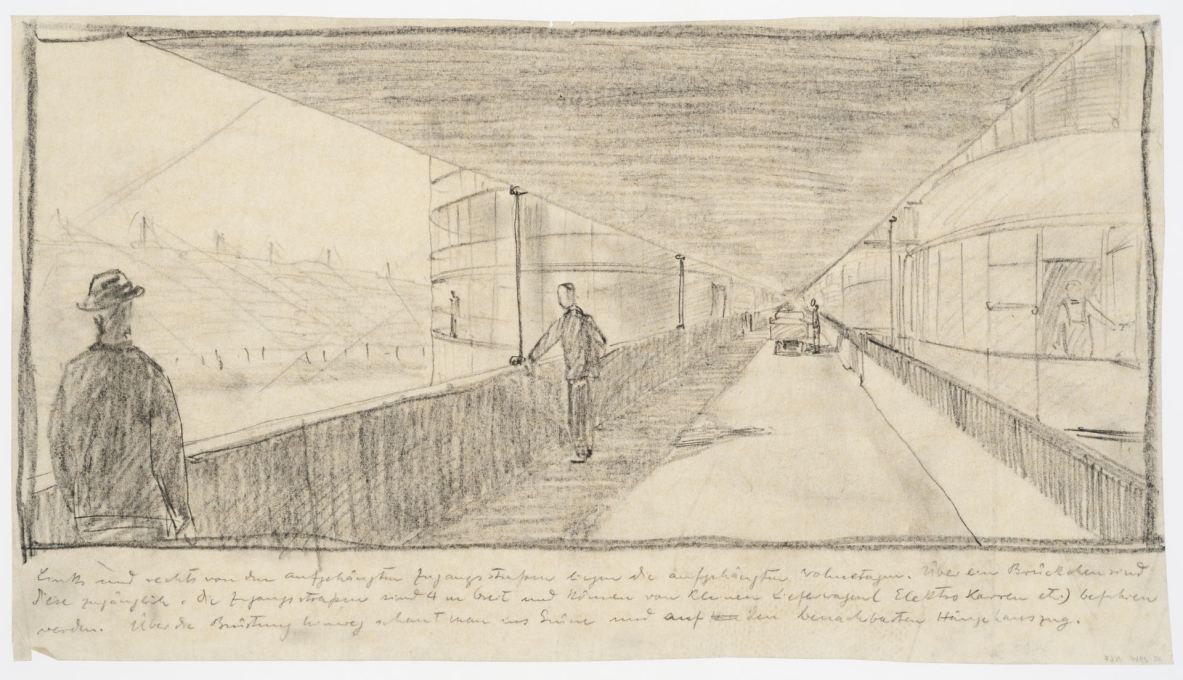

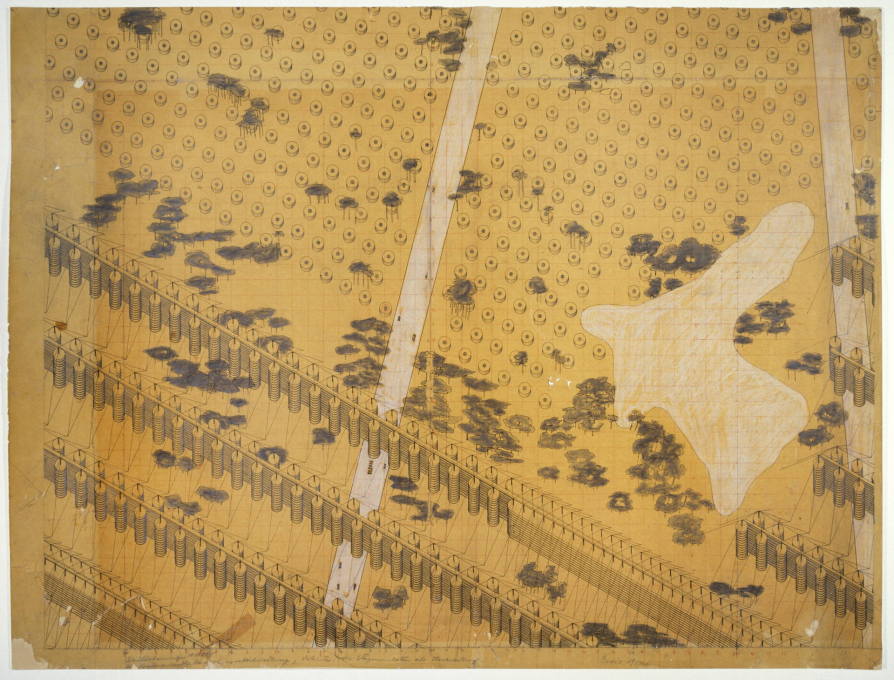

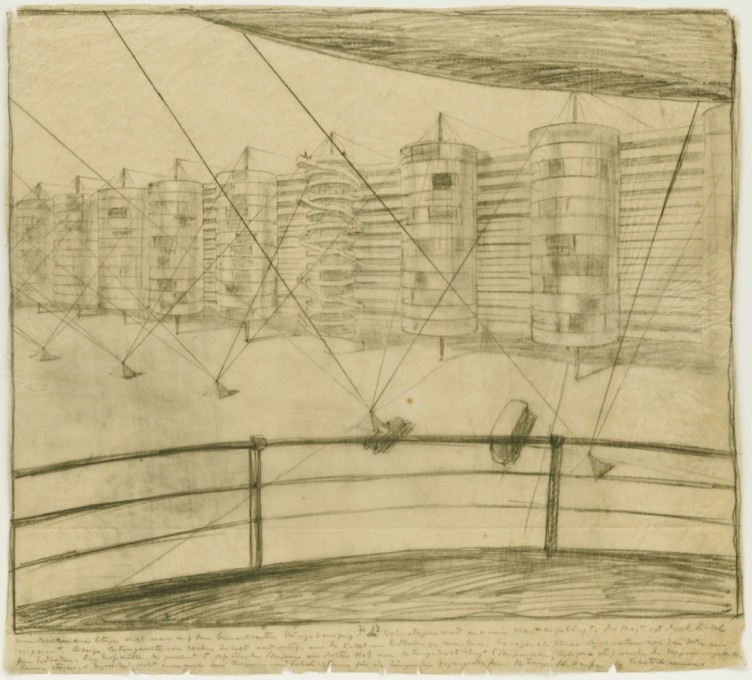

Finally, their attempts to get the recognition that they thought they deserved, imploded, with both brothers arguing with each other over the copyrights and attributions of their joint work. Add to this the global economic turndown after the 1929 Wall Street Crash and the fact that reportedly the brothers both fell in love with the same woman, the partnership of Heinz and Bodo Rasch ended in 1930 under a pretty heavy cloud. They dreamt of entire cities with suspended housing units, yet in the end the Haus Ernst Rasch in Bad Oeynhausen (1927) and the Haus mit auswechselbaren Wänden (“House with removable walls”) in Stuttgart (1930) were their only realised buildings.

While the exhibition in Herford claims that the legacy of their ideas continues until today – showing works like Kengo Kuma’s inflatable tea pavilion, Frei Otto’s hanging roofs for the Olympic Games in Munich and Karl Schwanzer’s suspended tower for BMW in Munich to back this up – it still remains pretty unclear how big the influence of the Brothers Rasch really was. Though bursting with huge creativity and enthusiasm, they were largely unable to get any of their radically modern design ideas – even those totally their own! – out there, let alone built. It is exactly this question mark hanging over the significance of their work that makes both the exhibition and its comprehensive catalogue – in particular their extraordinary drawings – so well worth exploring.

– Florian Heilmeyer

The Unfettered Gaze. The Rasch Brothers and their Influence on Modern Architecture

Until 1 February 2015 / FINAL 2 WEEKS!

MARTa Herford

Goebenstrasse 4-10

32052 Herford

Germany