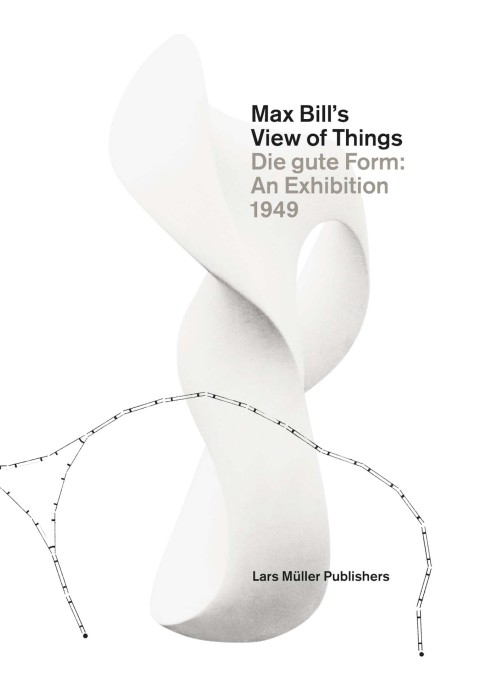

Max Bill’s controversial exhibition Die gute Form, shown for the first time in 1949, sought to define “good design” to a burgeoning post-war consumer generation. In his introductory essay to a new publication from Lars Müller Publishers documenting Bill’s initiative, Deyan Sudjic harks back to a time when design seemed so much simpler than it does today.

When the curator Kathryn Hiesinger organised Design Since 1945, an exhibition that opened at the Philadelphia Museum of Art in 1983, she invited both Ettore Sottsass and Max Bill to answer the same five questions and printed their responses in the catalogue. The first question was: “What are the qualities of good design?” Bill used just sixteen words to answer it. Sottsass needed all of three sentences.

The idea of “good design” (gute Form), has continued to resonate over the decades. Even now in our own relativist times, when no museum of design is comfortable with accepting the role of a pantheon containing nothing but examples of good design, when design is expected to ask questions rather than answer them, and when design endorsements from organisations such as Red Dot have become straightforward commercial transactions, the idea that there might be such a thing as good design continues to provide a faint background hum to the discussion. The concept of good and therefore also of bad design has been deeply ingrained into our thinking and our perception. It draws on the idea that a close enough study of the functional requirements of a category of objects or buildings will produce the best possible functional solution to the problem. This solution, it is believed, is one that will at the same time represent something that is also beautiful. In fact this is not a technical issue, but a philosophical one. At a poetic level, the functionalist ideal recalls these lines in John Keats’s “Ode on a Grecian Urn”: “Beauty is truth, truth beauty – that is all / Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know”. His words are a reminder that the functional ideal may be more aesthetic than utilitarian. And to suggest that there can be “truth” to materials is to suggest that there is a moral virtue to “good” design.

There is no question that this was also Max Bill’s View of Things. He was suggesting that good design was a kind of crusade. So did Sir Henry Cole, the guiding genius of the Great Exhibition in London of 1851 and the force behind the establishment of the Victoria and Albert Museum. Cole set up a display that was meant to demonstrate to the general public, to students, and to manufacturers, precisely what constituted good design. Alongside it was a demonstration of what Cole believed to be bad design. This display was called Examples of False Principles in Decoration and dubbed the “Chamber of Horrors” by Cole’s critics. In an echo of Cole, Stephen Bayley, director of the precursor to London’s Design Museum, the Boilerhouse exhibition space at the Victoria and Albert Museum, staged a show there titled Taste in the 1980s. Bayley placed objects whose design he saw as valuable on easels whereas others were impaled on dustbins.

The Council of Industrial Design was established in 1944 under the leadership of Gordon Russell, a designer and manufacturer of furniture, who represented the last gasp of the Arts and Crafts tradition. It later became the Design Council and staged the moraleboosting exhibition Britain Can Make It at the Victoria and Albert Museum in 1946, just before Bill’s exhibition. It filled the entire museum before its permanent collections, which had been evacuated during the war, were brought back to London. These were exhibits based on new designs from British manufacturers that were aimed for the export markets, alongside experiments with new materials, and with new typologies. On the crest of this wave, the Council of Industrial Design established Design magazine in 1949, a publication dedicated to the same mission of preaching the gospel of good design. In its pages it seemed that nothing had changed since Henry Cole’s chamber of horrors. A century later Design’s editors were still railing against wheat sheaf ornament applied to the sides of electric popup toasters. Russell, the Council’s first leader, asked: “What do we mean by good design? First, does it exist? It is often said that there is no such thing as good design or bad design, that design has no real measurable standards, that it is just a measure of personal taste; that because an article sells in great quantities, this alone proves it must be well designed” – apparently taking a swipe at Raymond Loewy and his famous TIME Magazine cover as the man who “streamlines the sales curve”.

Much the same things were being said in New York, where Eliot Noyes was appointed the first head of the newly formed department of design at the Museum of Modern Art in 1940. Like Max Bill, Noyes had been taught by several Bauhaus professors, although in his case it was at Harvard rather than in Dessau. Noyes, briefly Marcel Breuer’s partner, wrote that “good design in everyday objects shows the taste and good sense of the designers. On none is there arbitrarily applied decoration [ … ] These things really look like what they are”. While he was at the Museum of Modern Art Noyes curated Useful Objects of American Design under $10, an exhibition in which he set out to demonstrate that America was full of good, anonymous design, showing objects that he discovered in hardware stores and office supply companies. He followed this in 1944 with Design for Use, when he suggested that “A good design should have nothing that is irrelevant, accidental, or unrelated to the main idea. It is discouraging to see how many automobiles this year have been disfigured by cheap tricks. The most obvious is the undisciplined use of chrome. Bright metal accents can certainly be used when related to the whole design with care and thoughtfulness. As used on a number of cars, they are trashy, and when some of the twotone colour schemes are added, they are worse. There are many other offensive little details. For example the little portholes on the side of the Buick are deadend plugs – pseudoutilitarian decoration. The charitable thought strikes one that perhaps the sales department forced these gimmicks down the throats of reluctant and unhappy designers, and that even General Motors could produce a work of art if freed from such compulsions.”

Noyes left to work for IBM, but his successor at the Museum of Modern Art, Edgar Kaufmann, was just as dismissive of the American approach to industrial design, as represented by Loewy, Norman Bel Geddes, and Henry Dreyfuss. “A frequent misconception is that the principal purpose of good modern design is to facilitate trade and that big sales are proof of excellence in design. Not so. Sales are episodes in the careers of designed objects. Use is the first consideration.” An exhibition that Noyes curated at Yale while teaching there was titled Modern Design, the Search for Appropriate Form. It included what was described as “a room of welldesigned objects” alongside a display of vernacular, anonymous objects to suggest that “appropriate form often develops naturally.” The exhibition comprised the following manifesto:

Good Design

1 Fulfills its function

2 Respects its materials

3 Is suited to the method of production

4 Combines these in imaginative expression

It is a formulation that closely reflects Bill’s selection.

In her exhibition in Philadelphia, Hiesinger was attempting to demonstrate the polar opposites in postwar design. In 1983 Sottsass had just established the Memphis Group. For Bill, who had been the cofounder of what he hoped would be the natural successor of the Bauhaus, the Ulm School of Design seemed like its antithesis. As Hiesinger pointed out, both of them were painters and architects, as well as designers, polemicists, and writers. Despite all appearances to the contrary, Sottsass and Bill had once been closer in their attitudes than the disjunctive caricature of playful anarchy set against sober rectitude might have suggested. Sottsass had met Bill for the first time at Arte astratta e concreta, the exhibition that opened in Milan’s Palazzo Reale in January 1947. It was the launch of the Movimento per l’arte concreta (MAC). A decade later, when he was at Olivetti, Sottsass’s first two employees were both Ulm graduates. Tomas Maldonado, Bill’s onetime protégé, who was later to become his bête noire at the school, led the research project on which the keyboard for the Tekne 3 typewriter designed by Sottsass was based.

By 1983 Bill and Sottsass were philosophically far enough apart for Hiesinger’s stratagem to succeed perfectly. Bill’s answer to Hiesinger’s question was satisfyingly brusque. “Good design depends on the harmony established between the form of an object and its use.” Sottsass was equally satisfyingly subversive. “This is a question that supposes a Platonic view of the situation, that is, it supposes that somewhere, somehow, there is a place where GOOD DESIGN is deposited. The problem then is to come as close as possible to that ‘good design’. My idea instead is that the problem is not to be near ‘good design’ but to design, keeping as near as possible to the anthropological state of things, which, in turn, is to be as near as possible to the need a society has for an image of itself.” Hiesinger’s second question was to ask how these values endured in the face of technology. Bill replied that “technological changes should help to make the object better and more harmonious in form and in function, as well as cheaper”. Sottsass responded: “They don’t endure at all, because in my definition the qualities of good design are exactly the ones that don’t endure but follow the changes of history, the changes of the anthropological state of things. And among them, the changes of technology. If you really want to find something that endures, that is the intensity of the research for a relationship between history, and a possible image of history. In design what endures is man’s curiosity towards existence, and the drive to give a metaphoric image to it.”

It is the special quality of design that it is constantly shifting and adjusting its nature. Good design is a period piece. Design is constantly relevant, constantly fascinating. And in that, Sottsass’s answer was perhaps fuller and subtler than Bill’s, yet for all that there are aspects of Bill’s exhibition that continue to project a poignantly effective reflection of a world in which our aesthetic choices seemed so much clearer than they are now, a world for whose loss we cannot but feel regret.

– Deyan Sudjic is a writer, broadcaster and Director of the Design Museum London.

A longer version of this essay is to be found in the new Lars Müller publication: Max Bill’s View of Things, Die gute Form: An Exhibition, 1949. Reproduced with the kind permission of Deyan Sudjic and Lars Müller Publishers.