“Ruins are idealised garbage from a lost time...”

Whilst all eyes currently seem to be on Greek Finance Minister Yanis Varoufakis, uncube provides some further reading via our interview with the Greek architect and writer Aristide Antonas. His work consists of primarily speculative projects and theoretical writings, which explore the critical dimensions of the ongoing financial and sovereign debt crisis in Greece and the Eurozone, through contemporary Greek building culture and the social dimension of architecture.

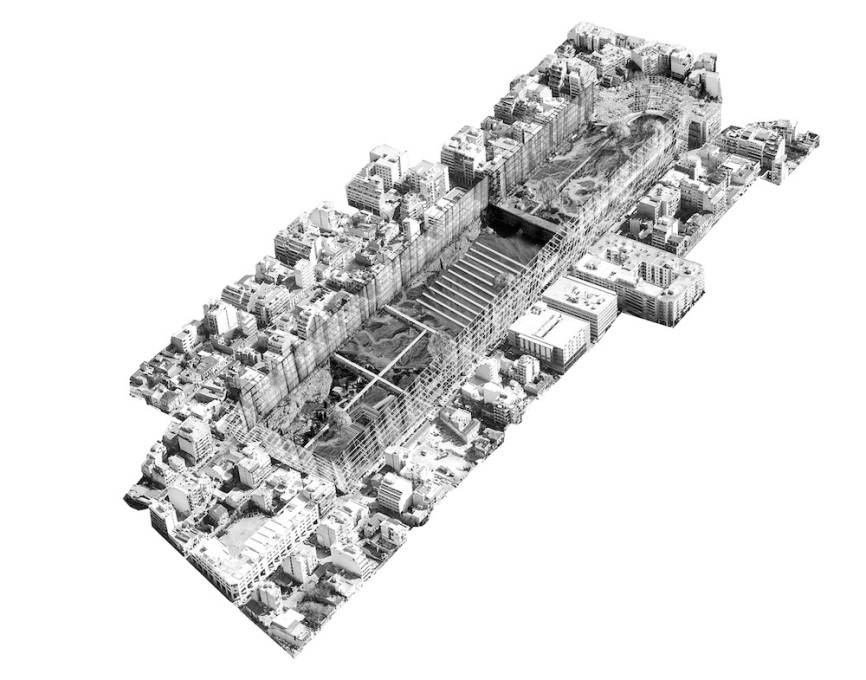

A new exhibition of his work at S AM, the Swiss Architecture Museum in Basel, Protocols of Athens, focuses on his projects for a city that he descibes as a “permanent ruin and permanent construction site” and a “test field” for “a next step after Europe”.

Your parents, Dimitris and Suzana Antonakakis, are renowned architects and founders of Atelier 66, a studio that sought to mediate between the global and local languages of architecture – so-called “critical regionalism”. How far did their approach to architecture influence you?

I would not believe someone who claims to not being influenced by their parents. Mine were close to the entourage of Team X, Aldo and Hannie van Eyck, Georges Candilis, and Alison and Peter Smithson were good friends with my parents and gave me advice. But I studied architecture thinking I would become a writer, believing that architecture school offered the best general education. Team X’s approach, with their criticism of the impersonal modern international style, was a given fact for me then. Maybe I am still suspicious today towards banal minimalism because of this. But at the same time, Team X’s rationale was not exempt from a nostalgic view of lost local cultures, which became sometimes caricatured in critical regionalism. I always felt that the past is impossible to reactivate. Nostalgia always marks a reference to a dead zone, an empty receptacle.

Currently a new vibrant cultural scene is arising in Athens and documenta 14 has even decided to establish a second site there. You’re very involved with the city – most of your projects are located in Athens, which serves as your test field and experimental site. How far does the city differ from other European capitals?

Athens has been hated up to now by its inhabitants. It has a very recent urban tradition: half its population comes from village culture, and independent Greece was still rural when it was announced as a modern country. Athens was installed as the capital of a new country to formalise the European memory of a lost ancient Greek civilization. Modern Greece was invented in a way by Bavaria, and Bavaria also organised itself at that time as an imaginary return to Ancient Greece. Today the relation between Hellas and Germania is entering a new phase; the European problem is schematised by this relationship, and the conscious interaction with the next documenta, directed by Adam Szymczyk, follows this tradition.

Athens is a test field for neoliberalism. This is why Athens became my test field, too. It became interesting because it has condensed a general problem in a specific place, namely the difference between global North and global South. The new order of dystopia in Athens has seen violent change in the city. On an urban level this is evident through the silent construction – still unstable but radical – of distinct city zones that would have been inconceivable in the past. They function as gated communities or as ghettos, as was the case for parts of the city centre before it was quasi-emptied of its immigrant inhabitants by the police. Europe has to be conscious of the camps of refugees that have been set up around Athens to complete a picture of this city. Athens is not a typical European city, but it condenses a growing problem of the European norm.

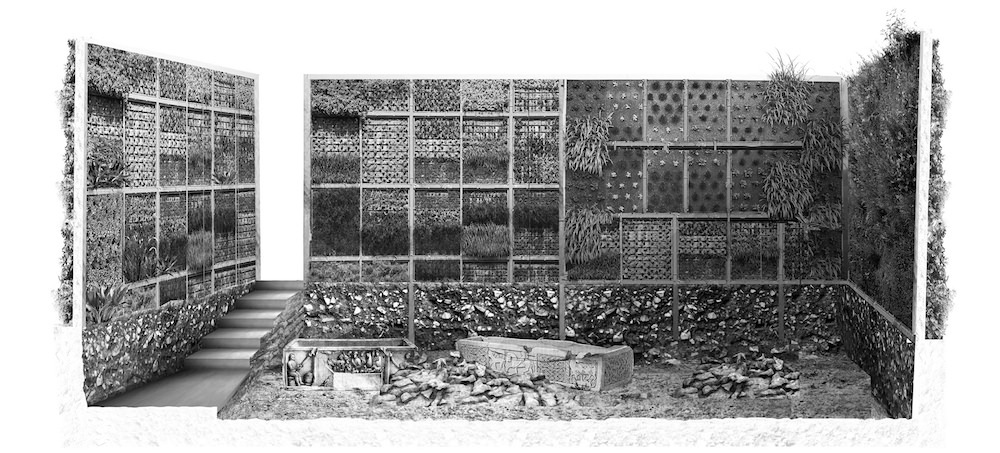

I think we can now invent in this city an abstract understanding of ruins, and I do not mean here only the ancient ones. In a sense, the European adoration of the ruin is linked to the analogous construction of fake ones. Follies or pseudo-ruins are not just the opposite of the real ruins; their fake character is also a “real” part of the ruin culture. Very few parts of the Athenian ruins are identified by archaeologists; most of them are ruins because they are traces of the past. But the unused old infrastructure pipes of modern Athens are also traces of the past. The new relation of Athens to its ruins is not didactic; we will not learn more about the ancient Greeks if we keep digging. But we could form landscape languages of remains and see how we can live next to them. The word “remains” is not only the enigma of archaeologists; it is the key word of a hegemonic global discourse concerning the anthropocene. Today we are obliged to inhabit a world of remains, of which Athens provides a privileged field. Ruins are idealised garbage from a lost time; we fetishise them by interpreting them anew.

Why is there in general such a lack of scholarly reflection on contemporary Greek architecture?

This is a difficult question. I know that there are people who really reflect on the architecture scene in an interesting way, but they don’t always survive in the academic scene, or they don’t write. You have to remember that the condition under which this scene operates is general despair. Nothing is easily optimistic. Writing and producing carry a last glimpse of hope.

In Athens, what is being tested is a next step after Europe. How can we abolish the European setting? This is the Greek question now. To be the living matter of such an experiment is a unique experience for all of us.

One tends to interpret your mostly unbuilt work, which is often based on ready-made material, as a kind of arte povera-inspired architecture in response to crisis and scarcity. How would you distinguish your work from the nowadays rather fashionable and often superficial implementation of re-use and recycling strategies?

The readymade tradition is one of the strongest in the art of the last century; readymades offer known material in the form of new questions. In this sense I understand that my work owes much to this already old Western tradition. It follows the investigation about archaeology or even the Wunderkammer rationale in a constructive way. On the other hand, I feel sometimes trapped in the banal nonsense of recycling. Re-use and recycle strategies repeat a deep moral banality: re-using ended up being the goal and not the means that would create something – as if we are trying to write and our text only expresses admiration of the ink we use. Re-use is not a meaning per se. It can be a language and it can form propositions, but I do not feel any moral obligation to re-use. I try to glue together different things, not recycle. The more the meaning of recycling becomes stable, the more it belongs to the hegemonic culture of today, and I become suspicious about its void messages and its hidden agendas.

The subtitle of your exhibition at S AM, the Swiss Architecture Museum, is “Protocols of Athens”, which calls to mind video games such as “The Fourth Protocol”. Do you propose a kind of new software for Athens?

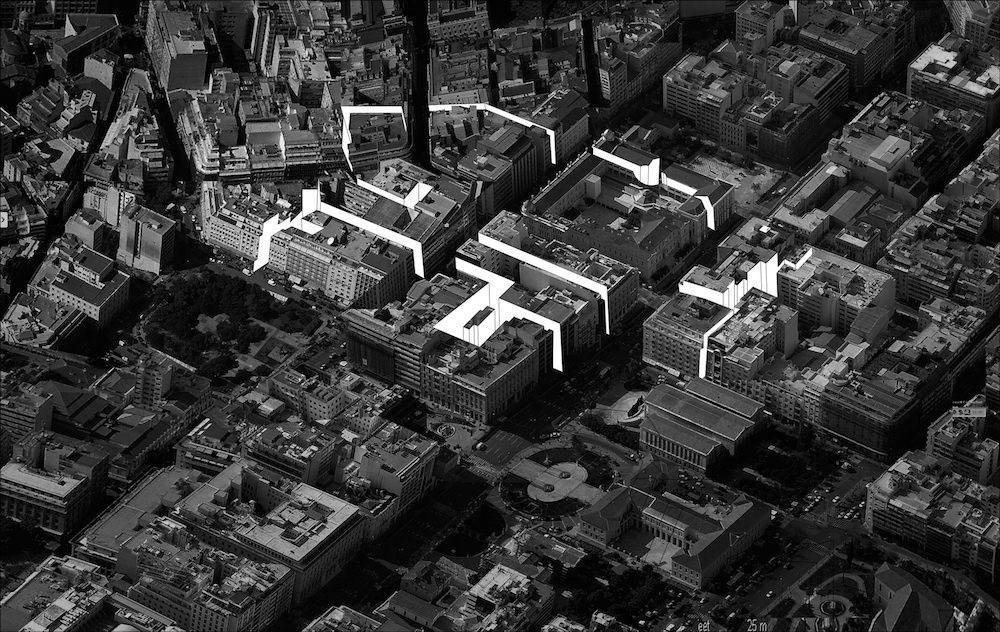

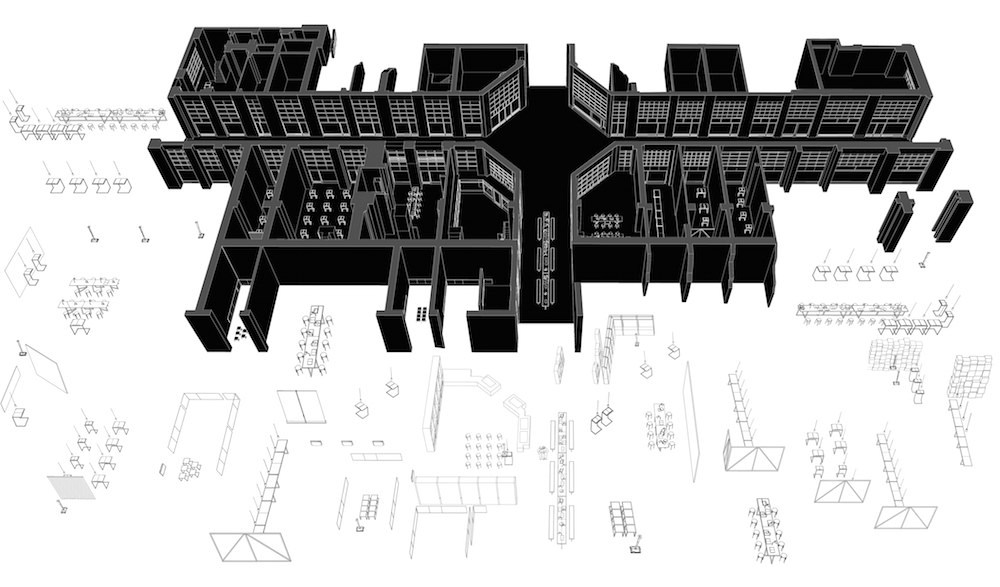

In a way, yes. But more in the sense of a theatre director who proposes mise-en-scènes for play scripts. With my understanding of protocols I try to underline the syntactic and literary aspect of architecture. Protocols are texts; the protocols of Athens are scripts that determine actions. An urban script can be read as a small-scale legislation or as a large-scale theatre performance, concerning the exchange of empty shops or the provision of open-air office space in deserted parts of the city centre. I would also call it “curatorial urbanism”. As a curator, one has to set up a series of issues and organise a discussion around topics.

A lot of your projects are strategies to upgrade the city; the programme has a pivotal role and seems to be much more important than the form. Where does your scepticism against form stem from? The crisis or a statement against self-referential starchitecture?

I have reservations concerning narcissistic morphology. I am never against architects, but buildings are sometimes aggressive; I resist them especially when they desperately want me to worship them. I prefer to discover and study a series of unimportant routines proposed by non-designed spaces. But the iconic is usually too simplistic and a quest for creating a distinctive form seems desperate to me; I don’t have a taste for architectural pirouettes. This is why the script or the programme becomes so important. Cedric Price is a figure I often return to. For him, buildings should serve the needs of those that use them.

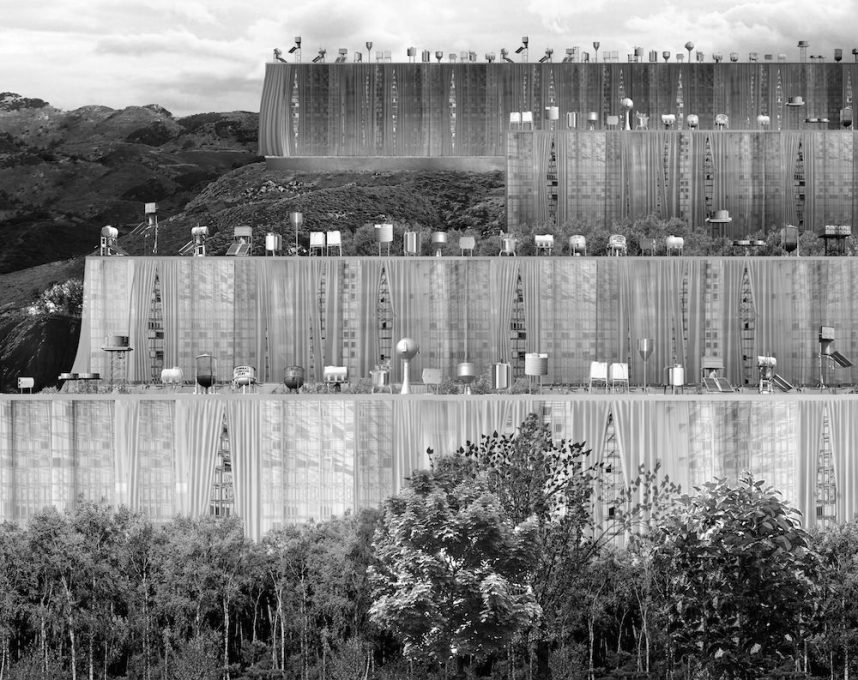

But what about the concept of use in contemporary Athens? I agree with Price when he writes that buildings have to be either transformed or demolished when they no longer match their purpose. But what purpose or performance can be hosted by a ruin? To script Athens differently, we may need to demolish some parts of it; this permanent flexibility very dear to Price could be performed in Athens not as a continuous rebuilding but as a selective and accurate system of demolishing. A permanent ruin and a permanent construction site staging repetitive occupations.

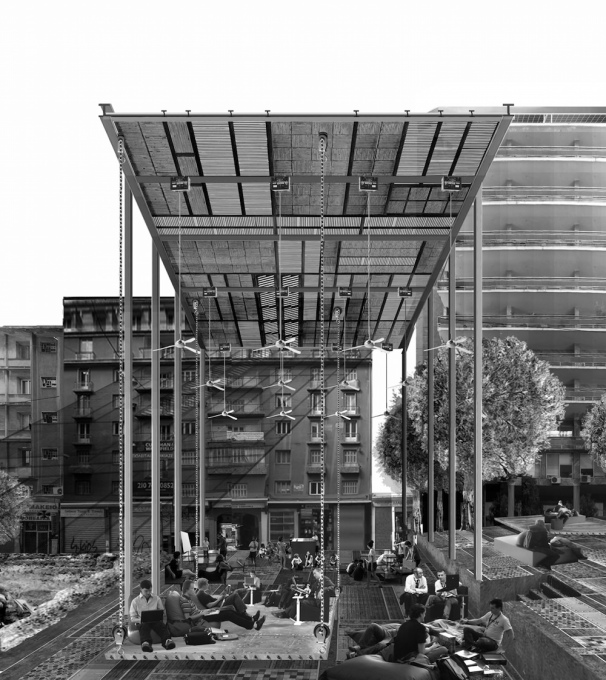

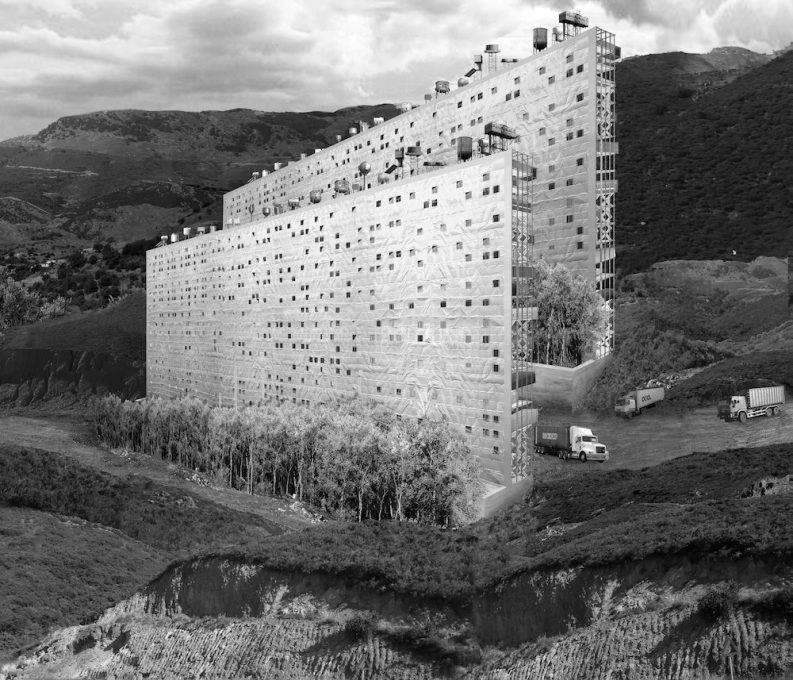

Your ideas and strategies are conveyed by very carefully made renderings and photomontages mostly in black and white. They have a very particular visual language. How does this visual representation reflect your vision?

I use them in a similar way as a terrorist uses bombs: to get more attention. Through the drawings the projects form a sequence of the same distinguishable series; through them one knows that another work has been done by our office. I am surprised, though, when people consider them as images to be framed and hung on the wall. They are only a call to read more – or some notes for possible fictions.

– Evelyn Steiner is curator at S AM Swiss Architecture Museum and organiser of the exhibition “Spatial Position 9: Aristide Antonas. Protocols of Athens”.

– Aristide Antonas (*1963, Athens) is an architect and writer, currently based in Athens and Berlin. He is principal of Antonas Office, which has been nominee for a Mies Van der Rohe award in 2009 and the Iakov Chernikov Prize in 2011). He has been taught widely, in Greece (NTUA, Athens and UTH, Volos), at the University of Cyprus,at the Frei U Berlin and in London at the Architectural Association and the Bartlett UCL.

Spatial Positions 9: Aristide Antonas. Protocols of Athens

Open March 7 until April 26

S AM Swiss Architecture Museum

Steinenberg 7, CH-4051 Basel