At the Chicago World’s Fair of 1933, a pair of young architects, Nathaniel Owings and Louis Skidmore, realised a cable car structure of supersize proportions, first proposed by engineer William L. Hamilton. As two thirds of the practice SOM, Owings and Skidmore later went on to realise a fair few of the tallest buildings in the world. Ann Lui investigates the 600 foot structure that started their career. Read more about the fantastical architecture of World’s Fairs in uncube’s current issue No. 32: Expotecture.

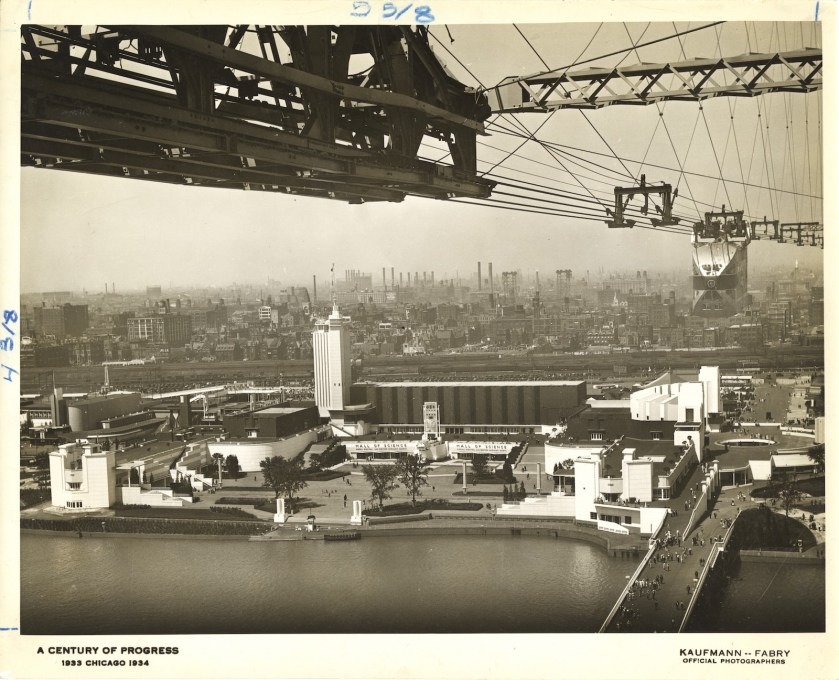

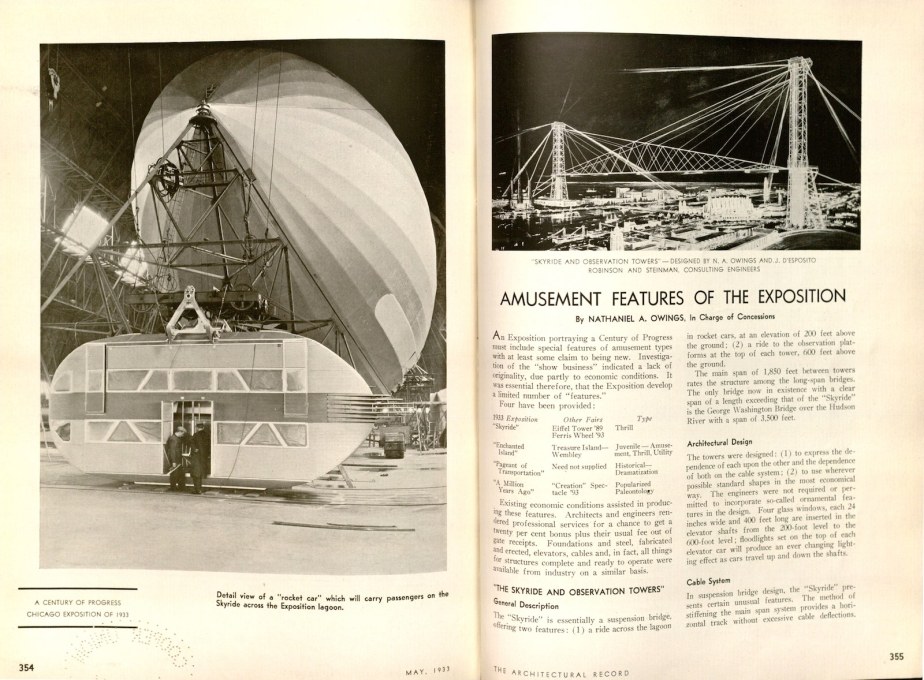

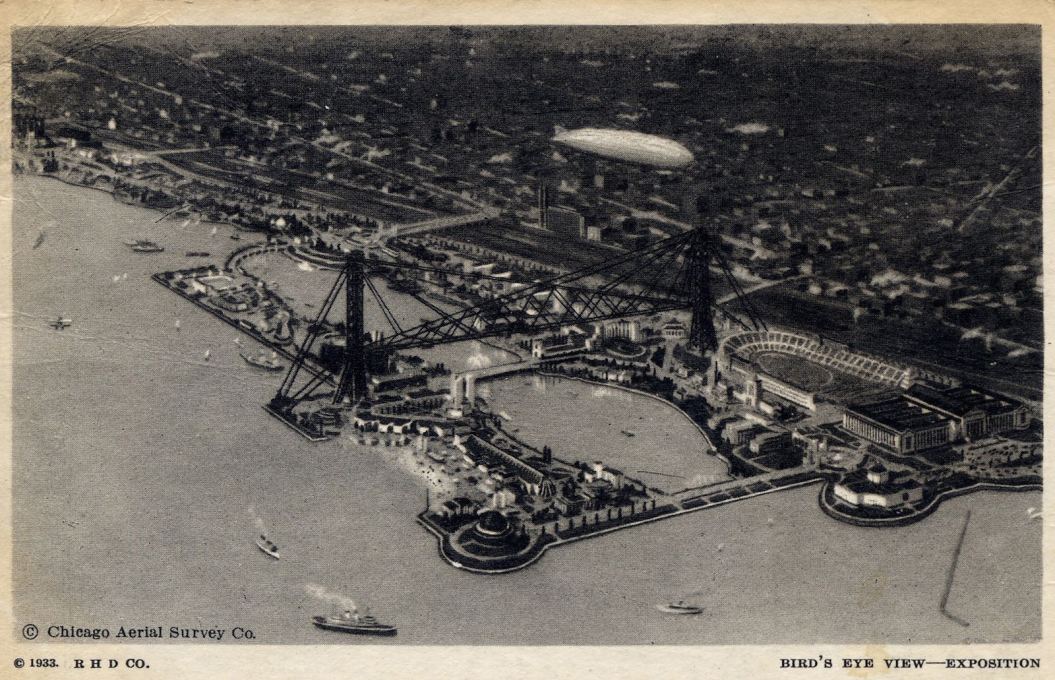

In 1933, at the Chicago World’s Fair entitled “A Century of Progress” – designed to exhibit, even against the backdrop of the depression, achievements in science and technology – one structure stood literally above the rest. Just above six hundred feet tall, the two massive steel towers of the “Sky Ride” stood higher than any of the city’s existing buildings. Between them, gondolas, advertised as “rocket cars”, shuttled visitors across the fairground over a central canal. Sheathed in rippled aluminium with an aerodynamic aesthetic, each “rocket car” allowed the viewer to gaze out in one direction over the Chicago city skyline, and in the other at Indiana with its distant steel factories. Of the Fair’s 48 million visitors, the majority had never flown before. The Sky Ride – while perhaps not quite rivalling the coasting of a seaplane or the lumbering cruise of the Graf Zeppelin – was marketed to its visitors as the sensation of flight delivered through the marvel of architectural technology.

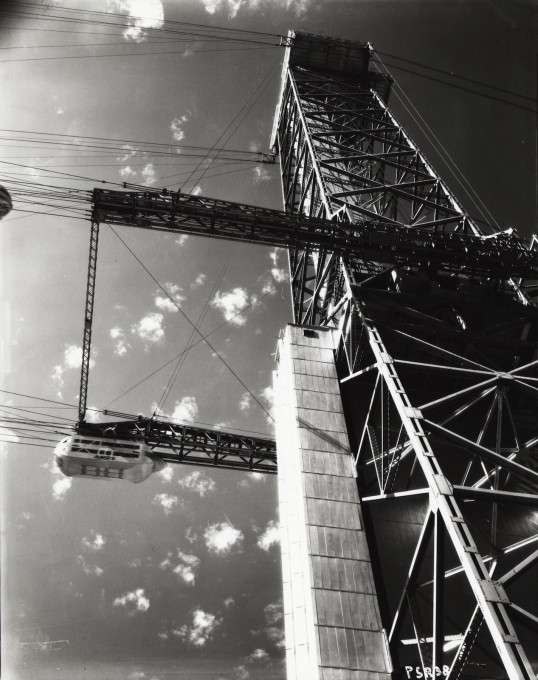

The Sky Ride offered more than a quick way to get from one side of the fairground to the other. It stood as a testament to new possibilities of construction. These towering interbellum “supertalls” were engineered by John A. Roebling's Sons Company, heirs of the engineer responsible for the Brooklyn Bridge, and were advertised as taller than any building west of New York, with the span between exceeded only by the George Washington Bridge over the Hudson. Architectural Record showcased the engineering of the suspension structure that spiderwebbed between the two towers in parallel with the Fair’s opening and highlighted steel cable 1.5 inches thick.

Originally conceived of by engineer William L. Hamilton, it was the two young architects, Nathaniel Owings and Louis Skidmore, aged 30 and 36 respectively, who finally realised the carnival ride after it had been tabled early on for its almost absurd scale. In the following years, these two designers, who were brothers-in-law, would go on to found the office of Skidmore, Owings and Merrill (SOM) along with the engineer John O. Merrill. The later exploits of SOM are well known and chronicled: the office’s growth over the postwar decades, to become for many years the largest architectural office in the United States; its name synonymous with the rise of the ubiquitous glass-clad office tower. Today, the firm is associated with the design of the tallest buildings in the world, from Burj Dubai to the new World Trade Center in New York. The Sky Ride, while predating the firm’s genesis, is an inspirational fragment from its incubation. The project’s scale, collaborative funding and development, and focus on architectural technology and expertise are an early example of the defining characteristics of postwar corporate architecture firms, of which SOM can be seen as the quintessential example.

Because of the Depression, a confluence of decreased funding for the Fair and lack of available opportunities in traditional practice drove Owings and Skidmore to work on this unconventional job and take some leadership despite their relative lack of practical experience. Skidmore was appointed the Chief of Design and Development; “Skid”, brought on his young brother-in-law Owings to be in charge of Concessions, and he took charge of the Fair’s many attractions. On one hand, the Fair was executed as “design by committee” – so much so the leadership turned Frank Lloyd Wright away for being “too much of an individualist”. This meant that many hands had a role in Sky Ride, a model of practice itself a precedent for collaborative, and anonymous, corporate design. On the other hand, young Owings and Skidmore’s roles, which amounted to the project’s rekindling, funding, coordination and execution, deserve a closer look. Owings, in his memoir The Spaces In Between chronicles the pair’s work on Sky Ride; his memories are corroborated by credit lines architectural journals from the time, the Fair’s guidebooks, as well the writings of the Fair’s general manager, Lenox R. Lohr, who calls Owings “largely responsible” for the gondola project. What were these two young architects learning from this odd job, when their peers were receiving training at traditional offices on Depression-era projects of more meager scale?

Early on, the Sky Ride project had been postponed in the planning phase for lack of funding and concerns about feasibility. The Fair’s Architectural Commission had been wading through a collection of wild speculations; projects they had ruled out included a thousand-foot-long giant pickle proposed by Heinz Corporation. However, something about the Sky Ride seemed to have held the imagination.

Owings, perhaps with the naiveté of the young architect, revived the project by acquiring, magpie-like, the “foundations, steel, cables, elevators, glass, concrete, paint, light fixtures” from in-kind donations from large companies, according to his memoir. He convinced these building material and services suppliers the value of exhibiting their products in action. The final backers of Sky Ride were a consortium of five: the Otis Elevator Company – providing the lifts carrying 20 people at a time in less than a minute to the towers’ tops, the Valley Structural Steel Company, Inland Steel Company, Great Lakes Dredge and Dock Company, and the John A. Roebling′s Sons Company.

Later on, architect Peter Smithson would comment on the way in which the office’s buildings were a decadent expression of technical expertise, a “cargo cult” of functionalism. The Sky Ride, in line with the broader curatorial direction of the Fair to show “process, not product”, could be seen as the model for this architectural exhibitionism in its curated showcasing of its component parts. More directly, the Sky Ride deployed technologies that would be crucial to the success of SOM′s later signature tall towers including the Otis elevator and Inland Steel’s structural elements.

The Sky Ride also foreshadowed a backroom type of networking between large companies and corporate architecture firms. In the postwar period, the same large organisations that had exhibited at A Century of Progress become SOM’s clients, including Pittsburgh Plate Glass, the Heinz Company (of the aforementioned giant pickle), and Inland Steel. In his memoir, Owings related how the Sky Ride may have foretold this web of connections: “As a joint venture developed by a group of big corporations voluntarily joining together, was there a trend here for a future in private practice?”

In Coney Island: The Technology of the Fantastic Rem Koolhaas argued “Coney Island is the incubator for Manhattan's incipient themes and infant mythology”. The spindly peaks at the “City of Towers” represented both symbolically and literally that of the “real city”, its phantom skyline lurking in the future. What Coney Island was for Manhattan, A Century of Progress may have been for Chicago’s nascent corporate architecture firms including SOM as well as Perkins+Will, Epstein, Goettsch Partners, and C.F. Murphy Associates, today known as JAHN. The Sky Ride reflected the later signatures of SOM and its peer corporate architecture firms: buildings that were large in scale, both in the city and in the sky; funded and established by networking between large corporations; and providing aesthetic and practical demonstration of building technology prowess. At the Fair’s conclusion, the Century of Progress architecture was panned by architectural critics such as Talbot Faulkner Hamlin of The Nation, who called the exhibition’s buildings “symptoms of exhaustion and despair” and “escape phenomena, flights from the realities”.

Nonetheless, the Sky Ride was a hit amongst the Fair’s visitors; the towers were nicknamed “Amos” and “Andy”, after two popular radio show personalities, and it became one of the most frequented of the Fair′s features, with 4.5 million visitors, and considered a strong ticket draw for the Fair which concluded with money to spare, despite dire predictions for its prospects at the onset of the depression. Perhaps in this way, the project also serves as a nod to the way in which corporate architecture is often perceived as well liked by the crowds and its clients though not by the critics. Further perhaps, Sky Ride may have been in some ways a first sign of Chicago’s architectural re-awakening, in the form of the rise of the large architectural office, after 50 years of Louis Sullivan’s predicted slumber after the city’s previous World’s Fair.

– Ann Lui is a Boston-based architectural designer and graduate of MIT′s History, Theory and Criticism Program.