Ever since George Orwell’s famous novel, the year 1984 has been synonymous with a somewhat dark future. Yet when that year finally arrived in the Netherlands, it saw the completion of two very optimistic, experimental – and geometric – sci-fi housing schemes: the celebrated kubuswoningen in Rotterdam, designed by Piet Blom, and the far less known bolwoningen in Den Bosch. Revisiting the latter for uncube, our correspondent Anneke Bokern finds them in good shape, yet still as alien and futuristic in their suburban surroundings as when they first landed.

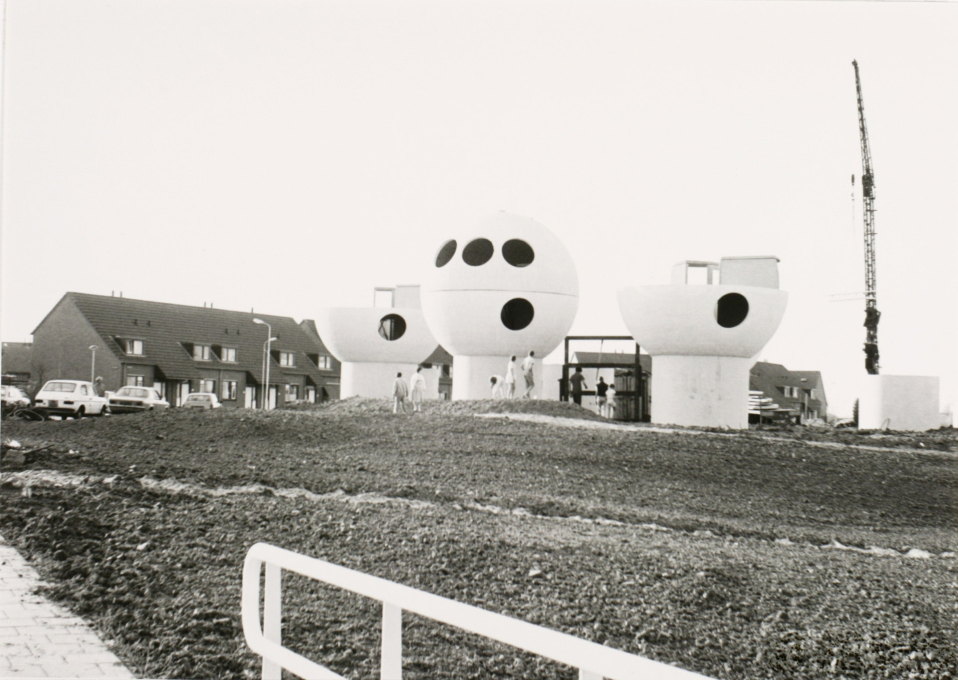

The neighbourhood of Maaspoort in the city of Den Bosch is a typical Dutch suburb from the early 1980s: little winding streets and liverwurst-coloured row houses with pitched roofs and tiny front gardens. Nothing could be more ordinary. But then something strange comes into sight. Next to a canal and a park in the middle of the suburb, embedded in unruly greenery, lies a field of 50 mushroom-like white globe houses, looking like the set of a 1960s sci-fi movie.

The bolwoningen (which translates as either “ball” or “bulb” houses/apartments) were designed in the late 1970s by idiosyncratic artist and sculptor Dries Kreijkamp and built in 1984. They share quite a few characteristics with the much more famous kubuswoningen (“Cube” houses) by Piet Blom in Rotterdam – constructed in the same year and conceived in a similar spirit. But while Blom’s Cube houses are just one more weird note in the architectural cacophony of Rotterdam, the bolwoningen are real aliens in their dull-as-ditchwater neighbourhood of a mid-sized town.

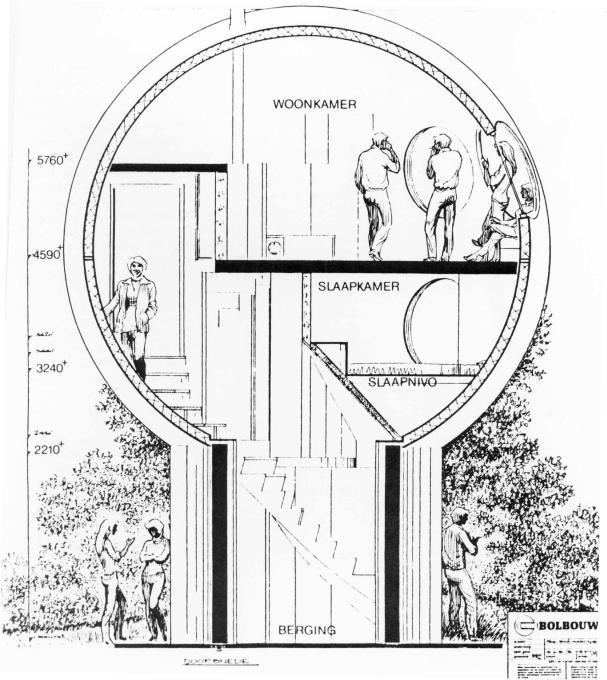

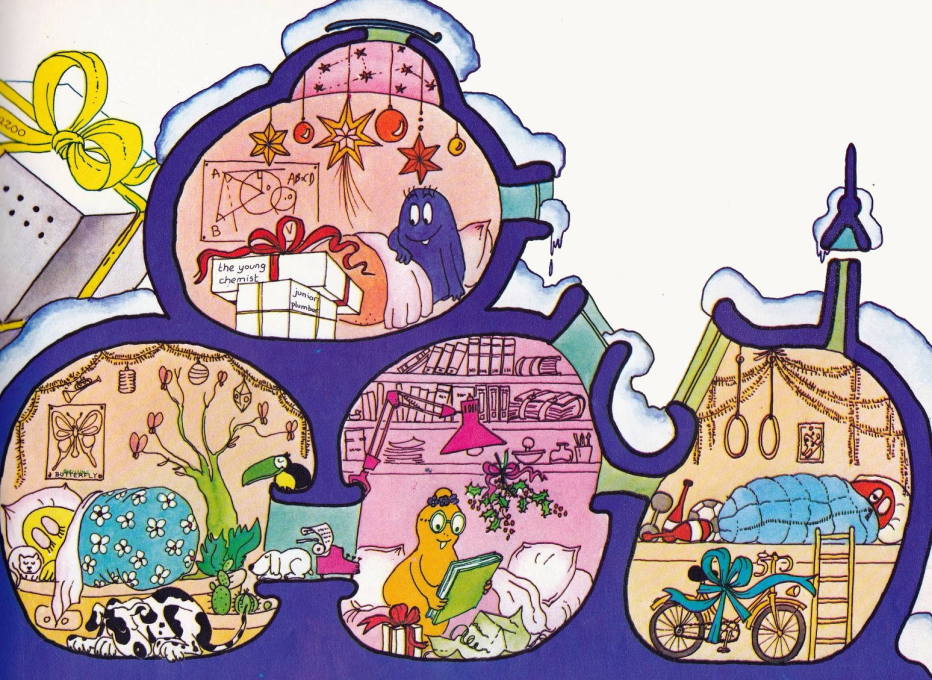

Like their angular urban cousins in Rotterdam, the bolwoningen stand off the ground on plinths – here cylinders that look like sort stalks. On entering the front door set into one of these “stalks”, you find a small storage space and a staircase leading up into the globe above. The staircase spirals around the inner skin of the sphere, leading first to the bed and then, past the bathroom and toilet, to the living area and kitchen. Six round windows with a diameter of 1.20 metres and a large roof light allow lots of daylight to enter the space. The light flows freely throughout the spherical space, which is divided by open platforms and interconnected functional areas instead of conventional storeys and rooms. Thanks to this layout, each ball house doesn’t feel cramped, although they only offer 55 square metres of living space.

Dries Kreijkamp, who died on November 26, 2014, was totally convinced by his creation. Born in 1937, he developed a fascination for spheres as an art student in the 1950s and 60s. “The Eskimos really knew what they were doing, with their igloos. And so do African tribes who build round clay huts”, he once said in an interview. “The globe-shape is totally self-evident. It’s the most organic and natural shape possible. After all, roundness is everywhere: we live on a globe, we’re born from a globe. The globe combines the biggest possible volume with the smallest possible surface area, so you need minimum material for it. It’s space saving, very ecological and nearly maintenance-free. Need I say more?”.

But as things went, his dream was more than slightly compromised when it came to realisation. The main reason for the houses being built at all was a special Dutch subsidy for experimental housing projects, created in 1968. Most legendary Dutch residential projects from the 1970s – such as the first Cube houses in Helmond and the Kasbah-complex in Hengelo – were funded by this subsidy. The bolwoningen project was the last to profit from it, before it was abolished in 1984. But the municipal housing department didn’t make things easy for Kreijkamp. The artist himself lived in a bolwoning complex in the town of Vlijmen, consisting of two and a half globes, sat on the ground and not on concrete cylinders. The houses in Den Bosch should have been built according to this model, but due to building regulations and intervention from the housing corporation Dreijkamp had to make several changes. The biggest compromise besides the stalks was the materials that were used: ideally, the globes should have been made out of polyester, making them extremely light-weight. But due to fire regulations they now consist of two cement concrete layers with glass-fibre reinforcement and rockwool insulation.

Despite the compromises, Kreijkamp was convinced that Den Bosch was only the beginning and that his globe houses would conquer the world. After all, journalists, architects and tourists came from all over the world to see them. Encouraged by the media attention, he geared up for mass production – which never happened. Over the next years, he put together hundreds of proposals and budget quotes for developing further sites, but never received a follow-up commission. In the middle of the 1990s, the housing corporation even considered demolishing the bolwoningen, because there were complaints about cracks and leakages, and one of the houses was sinking. A thorough renovation and the addition of storage space in the shape of little cabins attached to the stalks saved the globes, but didn't inspire the municipality to want more. “I offered to build a few more on an empty plot in Den Bosch”, recounted Dreijkamp. “The reply was: We already have some, thank you very much. I found this shocking in its ignorance”.

Dreijkamp didn’t give up though, and worked on the evolution of his creation until his death. He designed floating globe houses from polyester, powered by solar energy and wind turbines and equipped with an outboard engine, and even found a factory in Dubai which could have produced the polyester balls. “For 102,000 Euros you get a maintenance-free sustainable house, including flooring, bathroom and beds. What more could you want?” But just like the Cube houses, the bolwoningen were doomed to remain solitary prototypes, remnants from an era when government support made the strangest things possible in Holland.

– Anneke Bokern is an architecture journalist. Living in the Netherlands since 2000, she writes on Dutch architecture, art, and design for international publications. She is also a regular contributor to uncube.