A major retrospective exhibition of the work of Bernard Tschumi is currently on show at the S AM Swiss Architecture Museum in Basel. Tschumi, famous as the original great agent provocateur of deconstruction in the 1980s – his Parc de la Villette project in Paris launched a thousand student project imitators – has since developed a practice honed by an understanding of architecture as a discipline constantly in dialogue with other disciplines like film, art and literature. Evelyn Steiner of S AM talked to Tschumi about his practice, the influence of Cedric Price on his work and how after years of the dominance of form in architecture, the idea of architecture as a place of events is becoming current again.

The current exhibition “Bernard Tschumi. Architecture: Concept & Notation” at the Swiss Architecture Museum in Basel is the latest incarnation of your retrospective seen at the Centre Pompidou last year and the first overview of your work in Switzerland. Unlike in the French-speaking or Anglo-American worlds, you’ve received relatively little attention in Switzerland despite your Swiss roots. Why do you think that is?

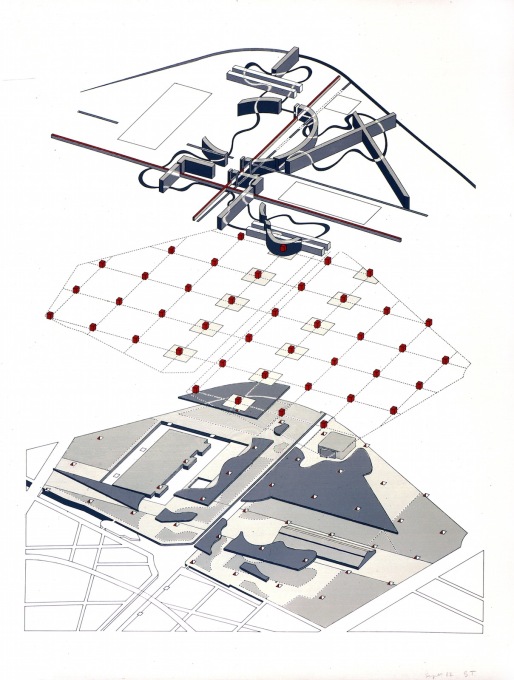

I have no idea! The first comprehensive exhibition of my work took place at MoMA in New York in 1994, 20 years ago. Though that show of course exhibited far less built work than is now in Basel, it already combined a lot of important projects: the Manhattan Transcripts, the Parc de la Villette and a few early competitions including the Bridge-City in Lausanne, Kansai Airport and the ZKM Center for Art and Media Technology in Karlsruhe. We’ve had a number of other exhibitions since including the Swiss pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 2006. But a direct relationship with Switzerland has mostly been established through buildings we’ve built: in Lausanne, Geneva and Rolle, but that was it. I don’t know why there’s never been an exhibition on my work in Switzerland. It’s just the way it is. I’m very happy to have the show in Basel.

How do you feel being confronted with your work in a retrospective, as a historical overview? Is there a strange sense of definitive-ness?

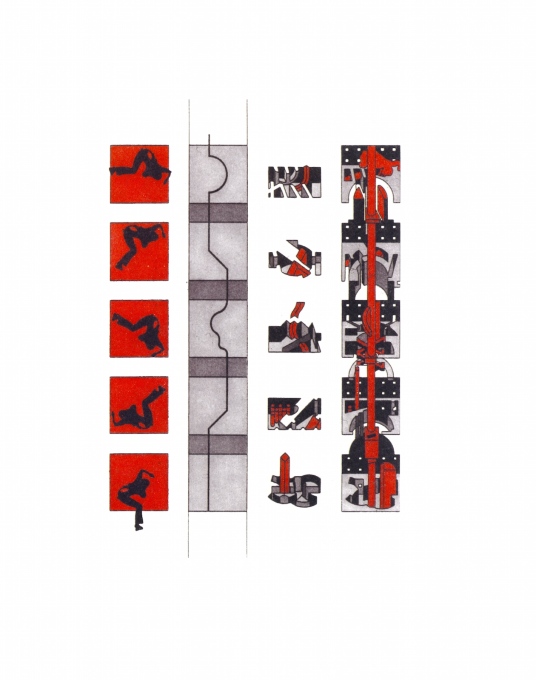

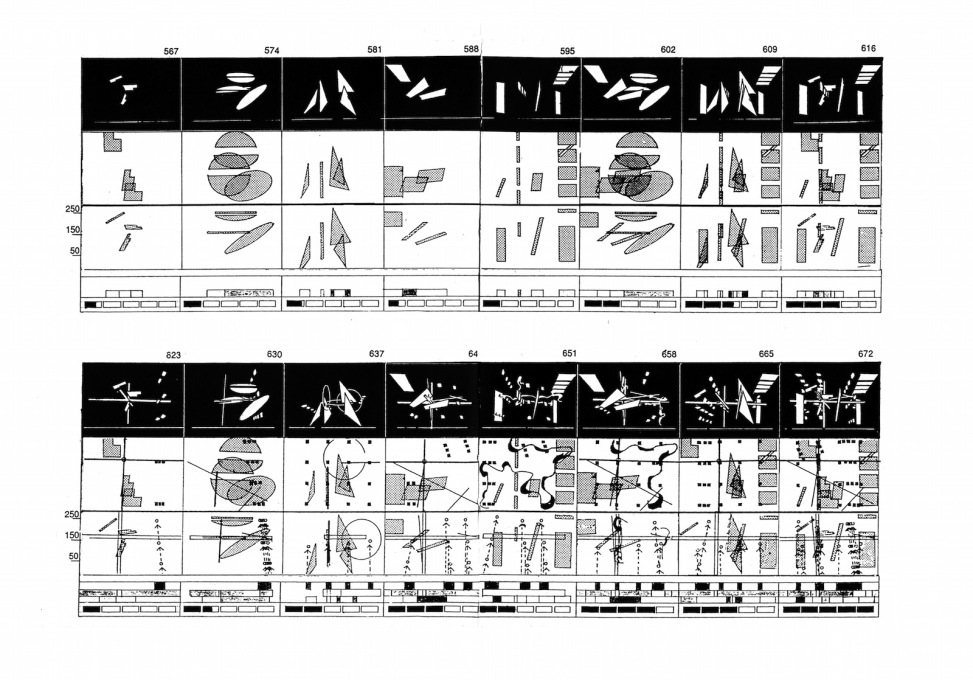

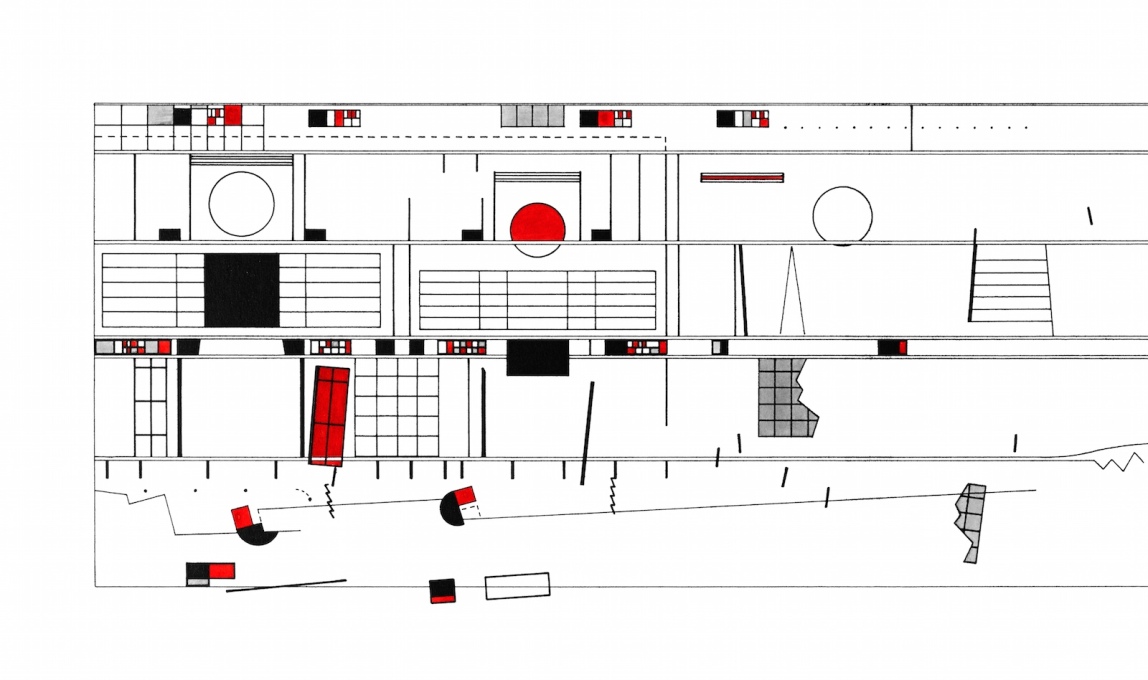

I wouldn’t call it definitive, but a stage. There are things which have been done and things in the making. The show as conceived for the Centre Pompidou was very much about both. Things done include my earlier research work of the 1970s, the Parc de la Villette of the 1980s, and a series of explorations, through projects but also through books: for example the Event-Cities series, consisting so far of four volumes, documents the research that goes with the projects. At one moment we decided to turn everything into a book as simultaneously documentation but also a sort of manifesto. This was published as the very big 770 page “Architecture Concepts: Red is Not a Color”, the first comprehensive treatment of my architecture. The theme was that architecture is importantly first as the materialisation of concepts and ideas. We worked seven years on the book, and then, apparently only two weeks after the book appeared on his table, Frédéric Migayrou, Chief Curator of the Centre Pompidou, called me. We developed the show relating to five parts of the book: “Manifestos: Space and Event”, “Program / Juxtaposition / Superimposition”, “Vectors and Envelopes”, “Concept, Context, Content” and “Concept-Forms”, following on from the Event-Cities series. We were trying to raise a few important questions, not about my architecture, but about architecture in general directing these questions towards a wider audience: not only architects, but people with an interest in cities and architecture.

Is it possible to mediate the intellectual and theoretical approach to your work through an exhibition primarily perceived in a visual way?

It’s difficult. I don’t know how it will work here in Basel, but at the Pompidou I was amazed to see people staying for an hour and a half, reading every caption and sitting down to watch the films; they were very engaged. It requires effort, but I hope this happens because for me architecture is not only the visual, it’s everything else, it’s the ears, the tactility, the sound, and it’s also the thought. You can’t take any of them away.

What’s your relation to the Swiss architectural scene and ETH Zurich, your alma mater? It seems somehow ambivalent: you once mentioned that your diploma Professor Jacques Schader and Bernhard Hoesli, the chairman of the school, found it difficult to give you a pass, because your final thesis project was heavily influenced by Cedric Price’s Fun Palace and your approach was not approved of in the conservative climate of 1969. Are there nonetheless traces of your Swiss architectural education in your architecture?

Well, it’s very ambiguous because the ETH in the 1960s was both very precise in its mandate and quite narrow in its definition of architecture as the art of construction within a very specific culture. But I worked very well with both professors who were very intelligently open – Hoesli had come back from the US, Schader was very objective and I have a great respect for the two. I was fascinated by the idea not of the present, but of the future and I saw it very much in the work of Cedric Price in England. It’s well known how I tried to invite Cedric to give a lecture at the ETH, but was told “no, you cannot, because his work is not architecture”! But I received a very “gründliche” or thorough grounding at the ETH and expanded it later at the AA in London.

You studied only six years before Jacques Herzog and Pierre de Meuron at the ETH, and share a similar educational background and foundation, yet developed in a very different direction. What happened within these six years? Was it only due to Aldo Rossi coming to teach at the ETH from 1972-1975, after you’d already left? His arrival is often seen as a turning point in the history of the ETH due to his rigorous approach, encouraging his students to think of architecture as architecture again after years of experimentation with sociological and philosophical methodologies...

I find it indeed very interesting that we studied only six years apart. Of course in between the political upheaval of 1968 happened, and on either side these two important figures: For me Cedric Price, for Herzog, Aldo Rossi. That period between the end of the sixties and beginning of the seventies was very short but very interesting historically.

Today, in the aftermath of the financial crisis, many architects have developed a scepticism of form as a kind of statement against a self-referential starchitecture formed by neoliberalism. Your definition of architecture as a space for events, not in terms of its form seems to have received fresh impetus and your own idols like Cedric Price are being appreciated again. How do you see this development?

I feel a bit ambiguous about it, because Cedric was simultaneously an inventor and political provocateur. He was questioning the idea of architecture with a big “A” but also inventing questions. What I mean is that quite often the answer is less important than the question. For example Cedric’s Potteries Thinkbelt project or the Fun Palace: these were not projects determined by others, they were really defined by the architect himself and a few people close to him, but they were not directly linked to the commercial or business requirements of society: they were a reading of the potential needs. Writing the programme was more important than designing the response in form of a building. Today I do not know if we are capable of doing this. I hope so!

The Swiss pavilion exhibition at the last Venice Architecture Biennial in 2014 was called “Lucius Burckhardt and Cedric Price – a stroll through a fun palace” and revisited the work of Lucius Burckhardt (1925–2003) and Cedric Price (1934–2003), to reflect on the future. What did you think?

I was happy that Cedric was talked about, but irritated by the spectacle aspect: of people pushing carts with reproductions of his drawings, trying – badly – to explain his work. To turn something that was purposefully, intentionally low key on the part of Cedric into a show, a zoo, was perhaps not the best way to ask the question.

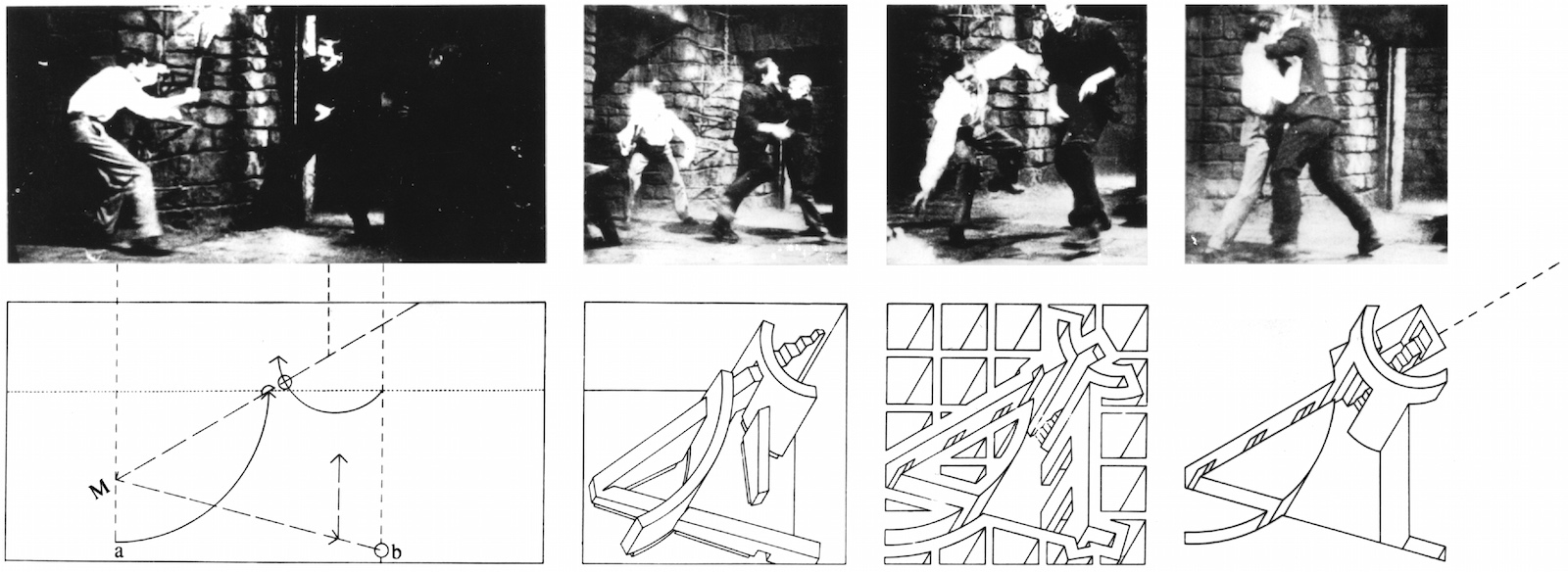

Film as a medium encompassing space and event had a great impact especially on your early architectural work. A lot of architects seem to have a passion or obsession for film, sharing similar practices in their perception and representation of space. Eisenstein was your hero and also Le Corbusier’s…

When film arrived as a completely new media, had to be developed: how you tell a story, how you literally invent the mechanics. But at the same it could be used for a purpose, for defending ideas, which is fascinating. You may also know of my own fascination for certain films of Jean-Luc Godard, his famous “Two or Three Things I Know About Her” and “Contempt”, which happens mostly in the Villa Malaparte in Capri. These films are fascinating commentaries, explorations even on the ideas of the city and the idea of the house. These are part of the discourse of space. I always insist that architecture is not about the knowledge of form, but the form of knowledge. But we are not the only ones who have the right to talk about this form of knowledge, others can talk about it, too. As an architect, I am allowed to make a film, I am allowed to write a book. I always say, that we are all in a society with an exchange, with import and export. I think what happens in film, what happens in art and in literature is as much part of my own work.

You have a strong interest in cities; you did your internship during your ETH studies in Paris, went to London after your degree and moved then to New York. Nowadays, you live and work in New York and Paris. Could it be you’ve escaped from Switzerland because of its lack of urbanity of vibrant mega cities?

Yes, definitely!

Now you are now working and living on both sides of the Atlantic, in New York as well as in Paris. There’s the saying to be “always on the wrong side of the pond”...Can you feel this inner conflict? Or does your bi-national lifestyle correspond to your work and theoretical thinking: nourished by paradox, contradictions and oppositions?

As far as I am concerned personally, no, there is no paradox. It is like I live in the same big city. In this metaphorical city there are two neighbourhoods I like best: one called New York City and one called Paris. I go from one to the other almost the same way you use to cross the Limmat in Zurich.

With every journey, you somehow make a mental spatial montage, a filmic cut between the two continents…

Yes absolutely. The journey is often seamless, what you could call in montage a fade in and a fade out. Some other times it is more of a jump cut, but it is still a normal thing. The reason I am on both sides of the Atlantic is purely because Paris and New York are the two cities I like the best and I don’t want to choose, I am not an American, I am definitely a European. But I love New York and I feel very much at home there. I have the main office in New York but I have another smaller office in Paris. For me and for my work it works well.

In reference to your seminal essay “Questions of space, the pyramid and the labyrinth (or, the Architectural Paradox)” (1975), which city is the pyramid, the city of reason, which one the labyrinth, the city of sensations?

That’s a very interesting question! It changes all the time. As you know, the pyramid and the labyrinth are complementary, so the two cities are complementary as well…

––––

– Evelyn Steiner is an architect and art historian and curator at S AM Swiss Architecture Museum.

– Bernard Tschumi (*1944) is the principle of the firm Bernard Tschumi Architects (BTA), which he established in Paris in 1983 with the commission for the Parc de la Villette, a 125-acre cultural park there. In 1988 the firm opened its head office in New York. Since then, projects have included the new Acropolis Museum; Le Fresnoy National Studio for the Contemporary Arts in Tourcoing, France; the Vacheron-Constantin Headquarters in Geneva; The Richard E. Lindner Athletics Center at the University of Cincinnati; two concert halls in Rouen and Limoges, and architecture schools in Marne-la-Vallée, France and Miami, Florida, as well as the Alésia Archaeological Center and Museum in France. He is a Professor in the Graduate School of Architecture at Columbia University, New York.

tschumi.com

Bernard Tschumi. Architecture: Concept & Notation

Until August 23, 2015.

S AM Swiss Architecture Museum

Steinenberg 7

CH-4051 Basel

Switzerland