More than 50 years after it was built, this Buddhist library building in Yangon in Myanmar, continues to exude the modern aspirations of its early days, while fulfilling its role as a site for traditional, spiritual learning. For Ben Bansal, one of the authors of a new guide to the architecture of Yangon, it is a building that like its American architect, Benjamin Polk, deserves more recongnition.

Tucked away off Kaba Aye Pagoda Road, Tripitaka Library is set within an overgrown park, several miles to the north of Yangon’s bustling downtown. If it weren’t for several red-robed monks entering and leaving the compound, one would hardly notice the place. Potted plants line the driveway to the main entrance stairs. Inside the library (the guard may take some convincing before he lets you enter), a few archivists work in a sleepy, tranquil atmosphere in the bright central atrium. Rows of yellowing Buddhist texts, kept under glass, line the walls.

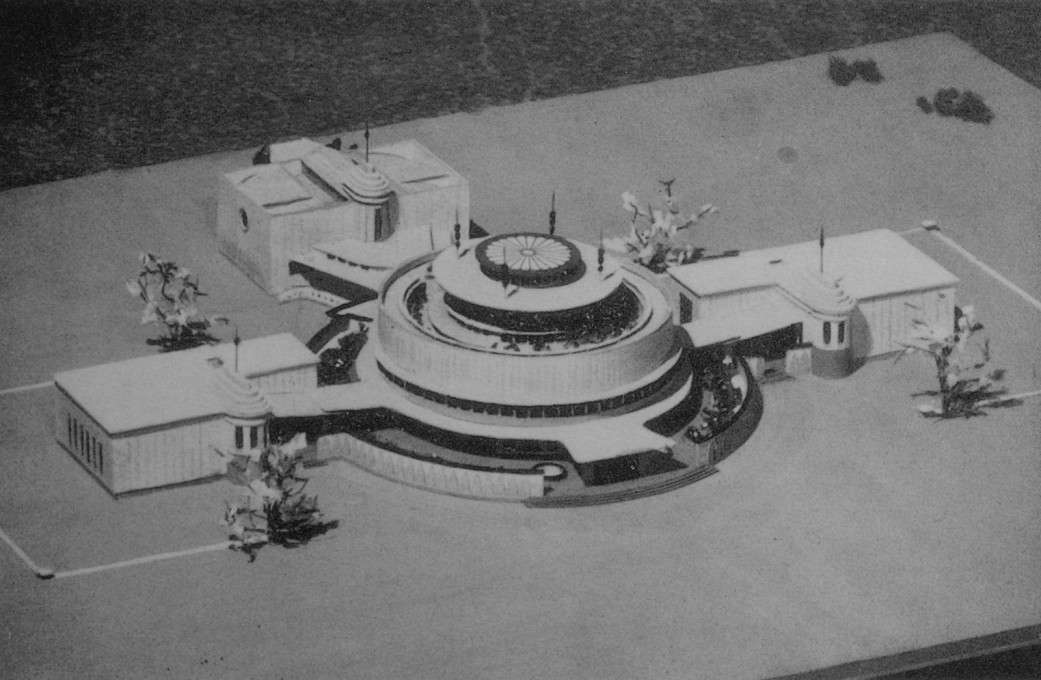

The area around the library was very different fifty years ago, when landscaped gardens and an artificial lake must have given the place a more ceremonial aura. Today trees and bushes hide the library’s three wings. However, the central building – with its light and radial design – still stands out, as does the surprising use of reinforced concrete as the chosen construction material. It is a favourite of local architects, U Sun Oo, Principal of Yangon-based firm Design 2000 describes it as a “successful, modern expression of Buddhist religious architecture”.

This is a magical building with its spiritual associations writ large – witness the two huge cast stone lotus flowers at the main entrance.“Tripitaka” derives from the ancient Pali language and translates as “three baskets”, denoting the canons of Buddhist scriptures. Burma’s first post-independence prime minister, U Nu, was a devout Buddhist and commissioned the library during his time in office. It was to hold the texts of the Sixth Great Buddhist Synod, convened between 1954 and 1956 in Rangoon (as Yangon was known until 1989). This council brought together 2,500 monastics from countries practising the Theravada branch of Buddhism, including Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, Sri Lanka and Thailand. Together they reviewed and recited the ancient scriptures. This Synod was a major project for the young nation, which gained independence only a few years earlier and was struggling with a brutal civil war and a chronic shortage of funds. 40 hectares of land were allocated to the project, and a million pounds sterling set aside for the construction of a pagoda, the Kaba Aye (or World Peace) Pagoda, as well as a vast manmade cave where the Synod’s lengthy proceedings took place. The authorities also built several adjacent hostels for the monks and a library: the Tripitaka Library – although the latter only opened several years after the Synod concluded. Not only was the Synod U Nu’s pet project – his legacy – it was also a spiritual anchor and source of pride for the Burmese population, the majority of which is Buddhist. Thousands of people came to offer their help during construction, and many more observed the proceedings.

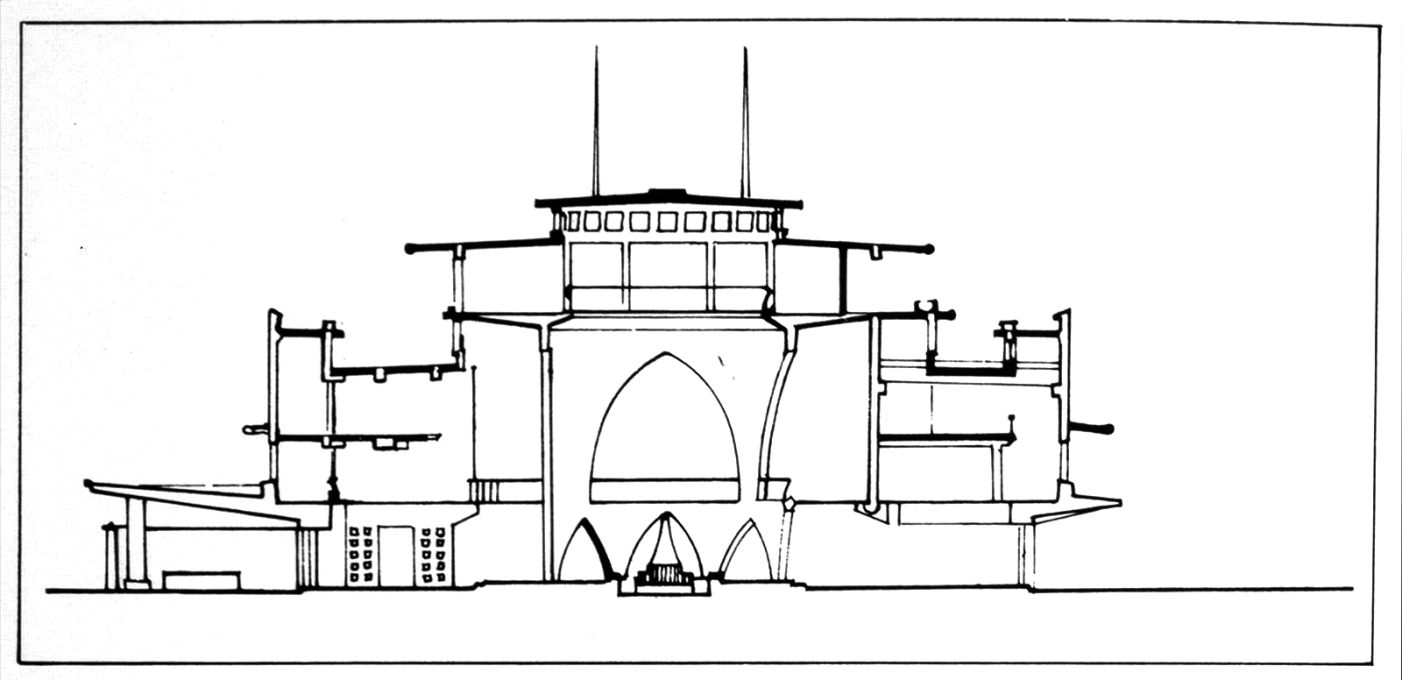

For the library’s design, U Nu commissioned the American architect Benjamin Polk (1916–2001), who had relocated to India in 1952 after practising in San Francisco for several years. He and U Nu were introduced and in 1953, Polk travelled to Bagan to study traditional Burmese architecture. He returned inspired by the pyramidal silhouettes and the pointed arches used throughout the ancient capital. Polk chose reinforced concrete for the Tripitaka Library becuase of the scarce availability of alternative building materials and limited construction skills. It also allowed Polk to use cantilevers extensively and to recess the pointed arches in the library’s interior, which come together in the centre of the building “like the stamen and pistil forms of a flower”, as the architect notes in his autobiography.

Polk incorporated a number of symbolic elements and numbers into the library: the radial design followed traditional stupa architecture, above all that of the Sanchi Stupa in Madhya Pradesh, India. Echoing the four noble truths (which comprise the essence of the Buddha’s teaching), the number four guided the ground plans and found expression in the four connected parts that together make up the library. Vertically, Polk expressed the number three – for example in the three storeys – following the three principles of existence in Buddhism: impermanence, suffering and insubstantiality. In other words, the building’s spiritual dimension was designed to take physical form. As Polk put it, “the one essential of the design can be taken to be that in the Buddhist sense, weight and mass became a living reality and a latent energy – a magic substance full of hidden activity”.

Undoubtedly, Polk was a pioneer in reconciling post-war modern architecture and its construction materials with his deep insights into Buddhism. He designed a modern yet traditional place of study and meditation. It still conveys the bygone optimism of the young country’s national building project, which, as we now know, ultimately led to decades of woe, violence and broken dreams. It also symbolises U Nu’s embrace of Buddhism as the state religion, a decision that alienated religious minorities and stoked political tensions.

Just a year after the library’s opening, General Ne Win grabbed power in a coup d’état, heralding the start of military rule and plunging Burma into international isolation. The generals continued to sponsor the building of new Buddhist pagodas and authorised the hasty renovation of ancient Bagan’s many temples, yet amid these projects, the Tripitaka Library remains a striking exception in its modernity of form. The building’s aesthetic doesn’t sit easily with the more authoritarian and rigid vision of state-led Buddhism which Myanmar later adopted. It dates from a time when the country dreamed of international leadership, brought together Theravada Buddhists from around the world, and invited a forward-thinking American architect to build a traditional building in its capital. Myanmar is a complex place, but as it re-opens to the world, perhaps the Tripitaka Library will now find a deserving place in the country’s collective memory.

– Ben Bansal is a co-author, with Elliott Fox and Manuel Oka, of the forthcoming Yangon Architectural Guide (DOM publishers, October 2015). He is also working on an exhibition about post-independence architecture in Yangon. @ben_bansal.

– All photos by Manuel Oka except for the four archival images, reproduced with kind permission from Abhinav Publications.