Kick-starting the revitalisation of Gothenburg’s Frihamnen port district, Berlin-based architects raumlabor have built the first structures in what will be a long-term participatory process to reactivate this area. It′s Sweden, so of course one of them is a sauna and the other is a public floating pool, both aiming to conquer the harbour basin and attract a broad new audience. Björn Ehrlemark reports through the steam for uncube.

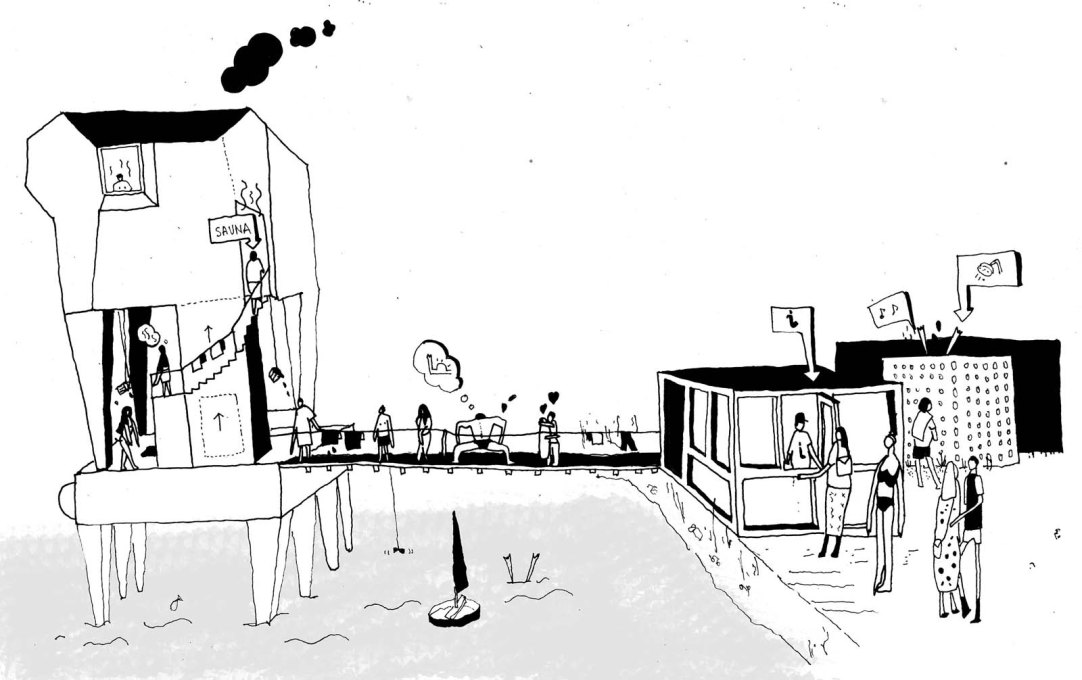

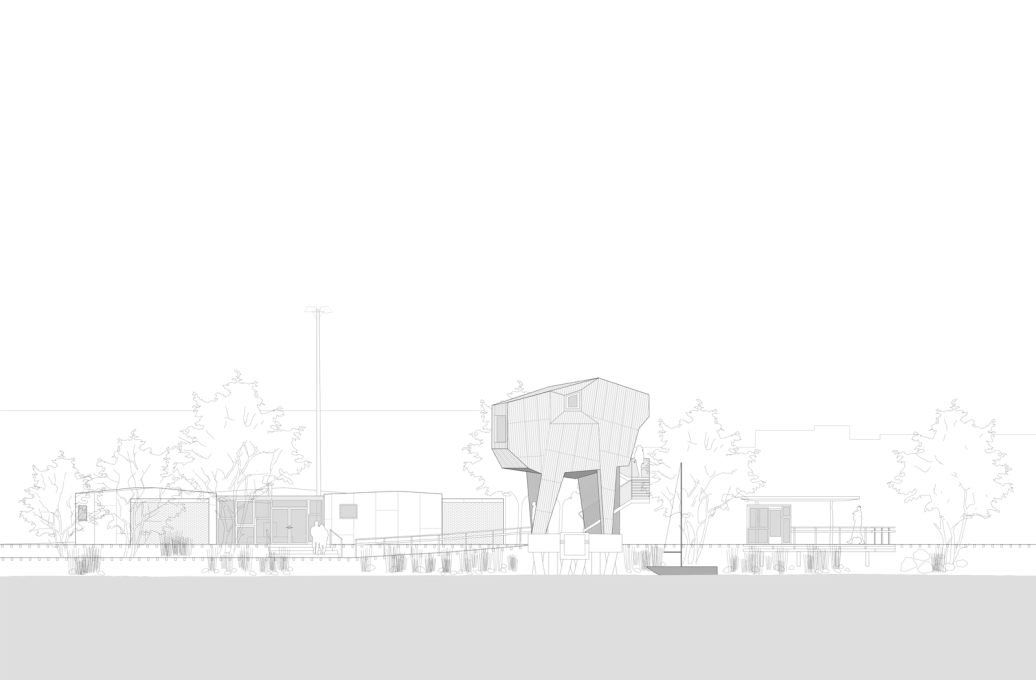

It stands a few steps into the black water of the harbour basin, balancing on spidery legs. Somehow it appears primeval and sci-fi at the same time. Not of this world, not of this time. Yet neither is true. The public sauna and adjacent floating swimming pool that German architects raumlabor have designed as part of Gothenburg’s Jubilee Park is an unlikely addition, but it could not have happened anywhere but right here, and right now.

Let us start at the beginning. By the mid-80’s, the Swedish state had cut its support programme for it’s shipyard industry, which had been on its knees since the Oil Crisis. For the country’s second city and Scandinavia's largest port, it was a hard blow. What could Gothenburg be, if not a city of shipbuilding?

In the summers of ‘86 and onwards, the industrial waterfront exploded in spectacles of sound, light and smoke as it became a venue for large-scale rock concerts. Michael Jackson, U2, Rolling Stones and Madonna brought huge crowds, most of which had never set foot on the north shores of the Göta River before then. This was the whole point. The strategy was to transform Gothenburg through something along the lines of “event urbanism”, promoting sports and hosting trade fairs and also to establish the obsolete docklands as an entertainment destination for the people (and future home-owners) of Gothenburg. Condos and riverside promenades followed suit, and entirely new neighbourhoods lined the river.

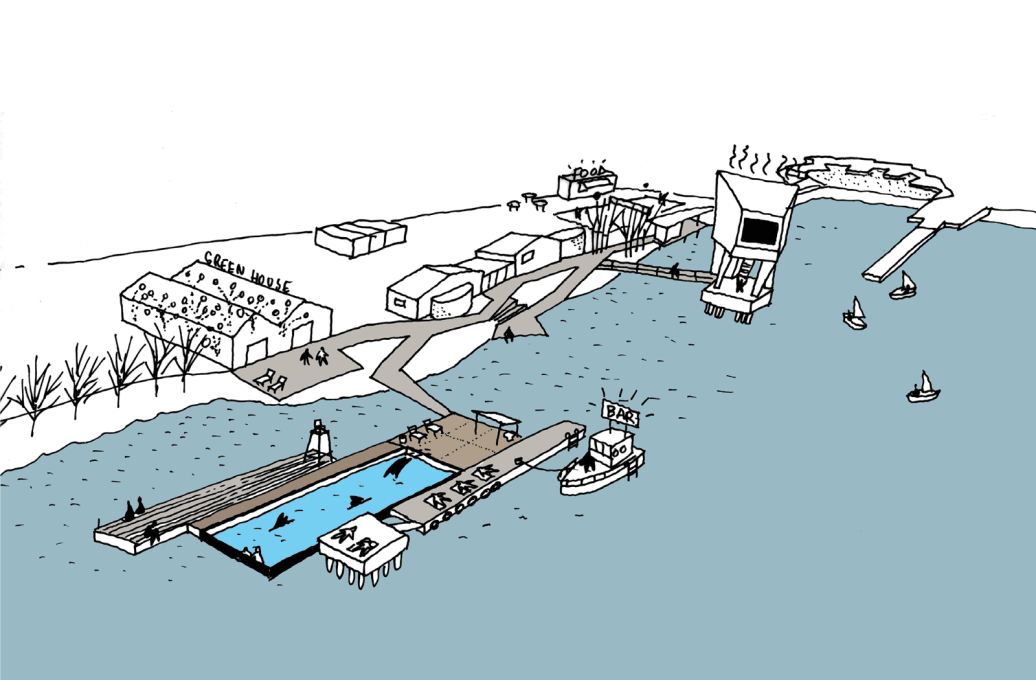

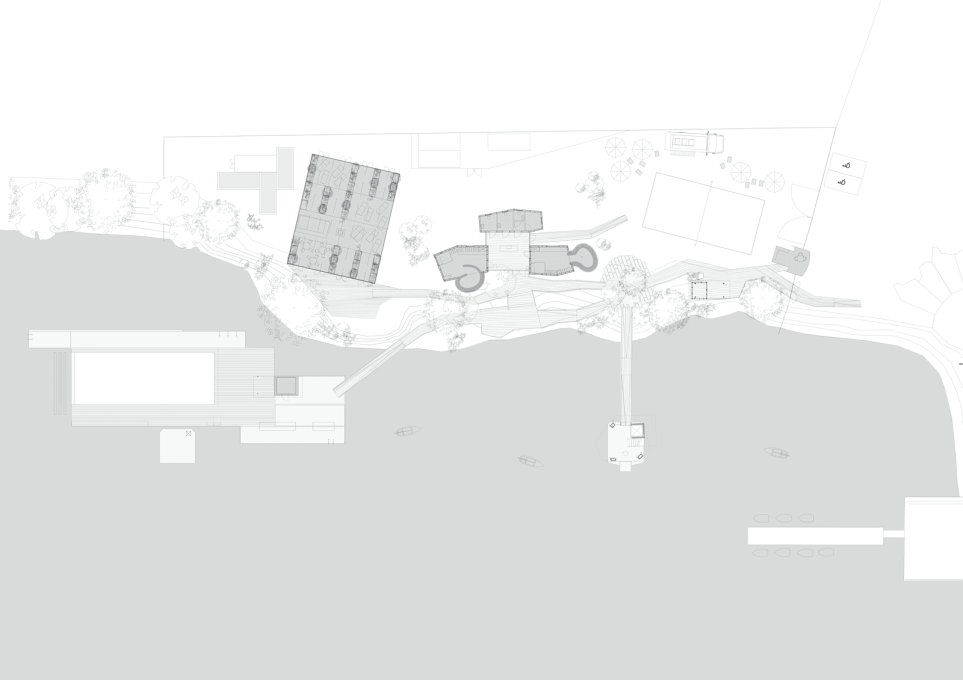

Today, the desolate jetty shoreline of Frihamnen is one of the last undeveloped port sites along the Göta River. Located less than a kilometre from Gothenburg train station, it is still a place were most locals never go. The site sits across from the historic centre and the municipality’s plan is to virtually double the size of the inner city by redeveloping this and two neighbouring industrial districts. It has become the focal point of the River City planning project, a long-term scheme for the riverbanks of the growing city. A new Jubilee Park, also located here, will celebrate Gothenburg's 400th anniversary in 2021. By then, one thousand workplaces, and as many dwellings, should already be in place, with fourteen thousand more to be added by 2035.

But what about the interim?

Enter Berlin-based architecture collective raumlabor and “Jubilee Park 0.5”, a strategy to activate Frihamnen and test architectural interventions in full-scale. Their new sauna and swimming pool are the first buildings to be erected, but other programmes are to follow. The architects have entered into a long-term engagement with the site, promoting a dynamic approach to urban planning that highlights processes and potentials. One where local citizens and stakeholders getting to know each other can be as important as the built outcome, they argue. One of the ways to achieve this is regular week-long workshops where volunteers are invited to assist with both conceptual work and manual labour. The Public Sauna and its facilities for changing rooms and showers, as well as the surrounding landscaping, has been constructed in this way, largely from re-used building material.

raumlabor have labelled “bathing culture” the guiding principle of the project. Whilst saunas are commonplace in northern Sweden, they are less common in urban parts of the south – especially public ones. Yet, a century ago so-called “cold water baths” were a mainstay of every coastal town in the country, and many remain to this day. Built for semi-public bathing, they often consist of a timber structure protecting visitors from cold winds and voyeurs, but remaining open to the water. Raumlabor’s bathing complex builds on this tradition, and the project explicitly sets out to establish a social space, free from competition, spectacle, and consumption.

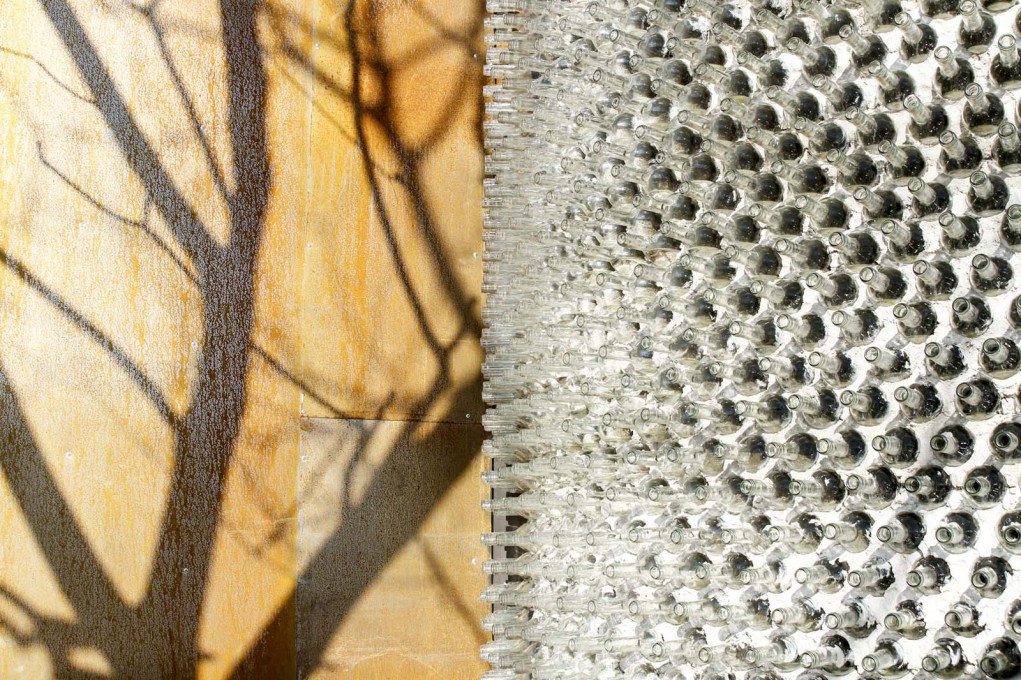

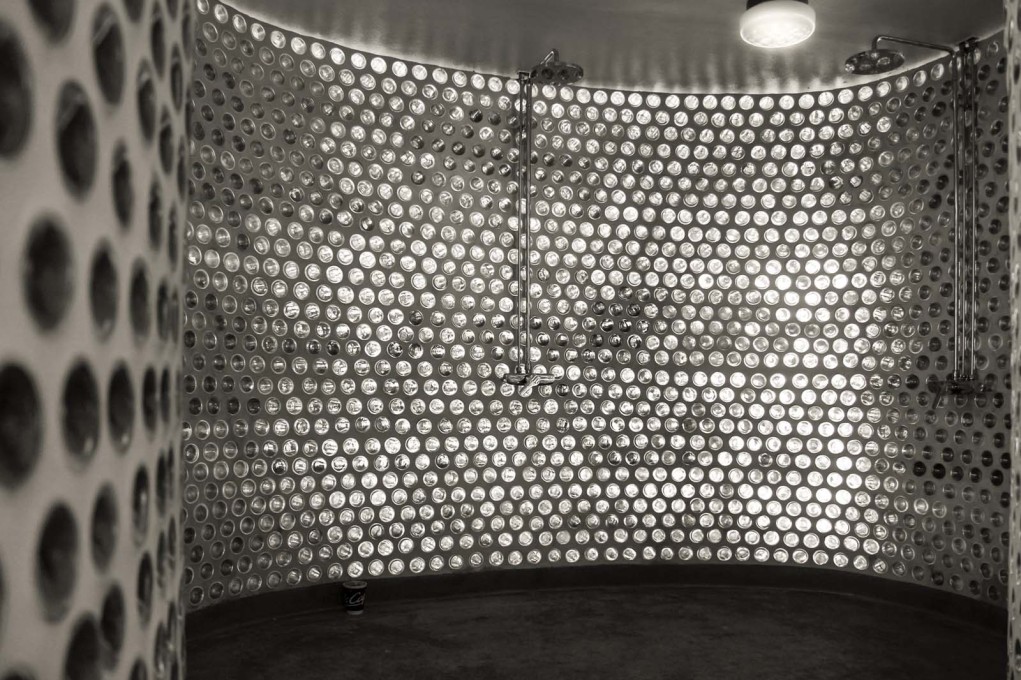

As an architectural typology, a sauna is elemental. A bubble of heat and steam, protected from the elements – indeed an open invitation for poetic architectural gestures. And the four-legged figure on the Gothenburg waterfront stands up well to the challenge. It is clad in a coat of rustic corrugated steel, has an embracing interior of wooded shingles, and the neighbouring glass rotundas are filled to the brim with shimmering natural light. It is quite beautiful.

But, perhaps more importantly to its authors, the Public Sauna also establishes a rare kind of non-commercial public space, in a context where shopping area and exploitation quotas are usually established long before any architects gets involved. A cultural institution in the guise of a bathhouse, it really has more in common with a public library than a spa retreat. In combining the most intimate of activities with the most public of environments, it is almost an architectural paradox. What is more, it seems to actually be working. The online booking schedule for the sauna is packed. Week after week, in three shifts a day, people meet and steam alongside twenty other naked strangers in the derelict old port.

Cynics could claim that raumlabor are unwittingly simply paving way for upcoming exploitation. Yet the strength of the scheme is that, regardless of any implicit intensions higher up the planning ladder, it manages to establish its own order. Rather than landing as a one-off event, it carves out a pocket of time where architecture and public space can gain a degree of independence and unpredictability that compressed official timelines normally will not allow. More than a lovely little building, what raumlabor has designed is a prolonged moment of reflection. How can this piece of the city, once a vital piece of infrastructure, serve its citizens in the years to come? If this was possible, what else can be done? And what else could we expect a city to do for us?

Peeking out through the steamy windows into the murky Gothenburg harbour, sauna visitors are likely to muse on some of these questions too. Without knowing it, they are given an opportunity to contemplate their city's future from a unique perspective: in informal conversation with friends and strangers, at a moment when everything is still possible. And one steam bath a time, the city is reimagined. In a few years time, the ideas for a new Gothenburg spawned in the belly of this creature could be in their thousands.

–Björn Ehrlemark is an architect and editor living in Stockholm where he runs the public programme of the KTH School of Architecture and co-directs Neighbours of Architecture.