The first Chicago Architecture Biennial has just opened – surprisingly the first ever architecture biennale in North America. As the birthplace of the skyscraper, the testbed for both Frank Lloyd Wright and his low-rise suburban houses, as well as for Mies van der Rohe and his downtown high-rises, the city is a natural fit for such an event. Rob Wilson reports on a Biennial rich in content – and context – but one that provides more of a wide smörgåsbord of ideas on “The State of the Art of Architecture” than any incisive critical comment on its possible future direction.

As Antoni Gaudí is to Barcelona or Charles Rennie Mackintosh is to Glasgow, Chicago is one of those cities associated with architecture and architects, although in this case it’s a whole bunch of them: Sullivan, Burnham, Frank Lloyd Wright, Mies van der Rohe and SOM, to name a few. So for the first architecture biennial in North America the city seems a natural host. Indeed the only surprise is that it hasn’t happened there before.

The city has recently upped its cultural game in other cultural areas, with the resurgent EXPO Chicago Art Fair for example, but in the architecture department it already has a clear advantage over most other US metropolises. There’s no need to construct a new iconic structure to brand the city, its existing architecture already does the job nicely, so holding an architecture biennial seems a clear way to leverage what it already has in order to attract profile, recognition, visitors and money to the city.

As such the Biennial is clearly a pet project of the city administration from the very impressive Mayor Rahm Emanuel (a former White House Chief of Staff to Obama who popped up at every opportunity during the preview days to spout his love for architecture) to the equally impressive Commissioner of the Department of Cultural Affairs, Michelle T. Boone, who has given over the Chicago Cultural Center – where her office is located – as the main Biennial exhibition venue.

And where power lies, money follows, with BP as the main – allegedly multi-million dollar – sponsor, here doing their bit of shoreline greenwashing five years after the Gulf of Mexico oil spill, by funding a series of architect-designed kiosks alongside the lake. And talking about buffing up images, SC Johnson, better known as Johnson Wax, are also prominent supporters of the event, offering free tours to their extraordinary Frank Lloyd Wright-designed headquarters at Racine, 60 miles outside Chicago throughout the run of the Biennial.

With such a fair political – and funding – wind, whispers of a slightly chaotic run up, were not in evidence at what appeared a very well laid out and organised event – with copious information and a informative guidebook (the catalogue by Lars Müller will follow later).

The kiosks and the series of architecture tours are just two of the most prominent off-site projects of the biennial – which also link in with other events presented by many partner organisations, including a David Adjaye exhibition at the Art Institute and the opening of a renovated bank building on the South Side of Chicago as the Stony Island Arts Bank, an initiative of artist Theaster Gates. But essentially the Biennial is centred around the primary exhibition downtown at the Chicago Cultural Center, curated by Joseph Grima and Sarah Herda, both ex-directors of that architecture powerhouse: Storefront New York.

This main exhibition is huge, reflecting the scale of the Cultural Center building (once the Chicago Public Library) built in 1897, its design and decoration fully reflecting all the confidence and civic pride of what was the fastest growing city of the nineteeth century: it is a big Beaux Arts neo-Roman/Renaissance mash-up, liberally coated inside with mosaic tiling, and a venue never before dedicated to a single exhibition.

The Biennial's title The State of the Art of Architecture – taken from a conference organised in the 1970s by another great of Chicago architecture, Stanley Tigerman – is not, as the curators were keen to underline, a theme for which they chose participants’ work as illustrations, but an umbrella headine for an open call for submissions, from which they then made a selection. In theory this allowed for a light curatorial hand whilst ensuring an overview of pressing global issues. This approach was reflected in a pecha-kucha type event during the opening, with (inevitably) Hans Ulrich Obrist presiding, which asked: what is urgent in architecture (and elsewhere)?

This led to an eclectic range of projects for inclusion, although as Herda described it, one primary theme that did emerge from the submissions was that of the “agency of the architect”, someone who is no longer just waiting around for a client or a brief.

The enormous scale of the Cultural Center building meant that full-scale building prototypes could be constructed in the spaces. These included a prefabricated, flexible housing model designed for mass-production by Vo Trong Nghia Architects from Vietnam and Tatiana Bilbao’s Mexican social housing prototype, able to be adapted to different climatic conditions and extended as needed. The latter was nicely juxtaposed in scale against Sou Fujimoto’s installation Architecture is Everywhere, with its minute models placing tiny human figures amidst the detritus of the everyday, from paper clips to bits of polysterene, imaginatively elevating these in scale to inhabitable structures.

In the same room the focus on social, affordable housing ran like a thread through several exhibitors work, including a fascinating film Imagineries of Transformation by Lacaton & Vassal, looking at alternative futures for the modernist public housing blocks currently being torn down by the French government, in particular their own repurposing of an estate in Bordeaux with its transformation of individual living spaces, rethought from the inside out.

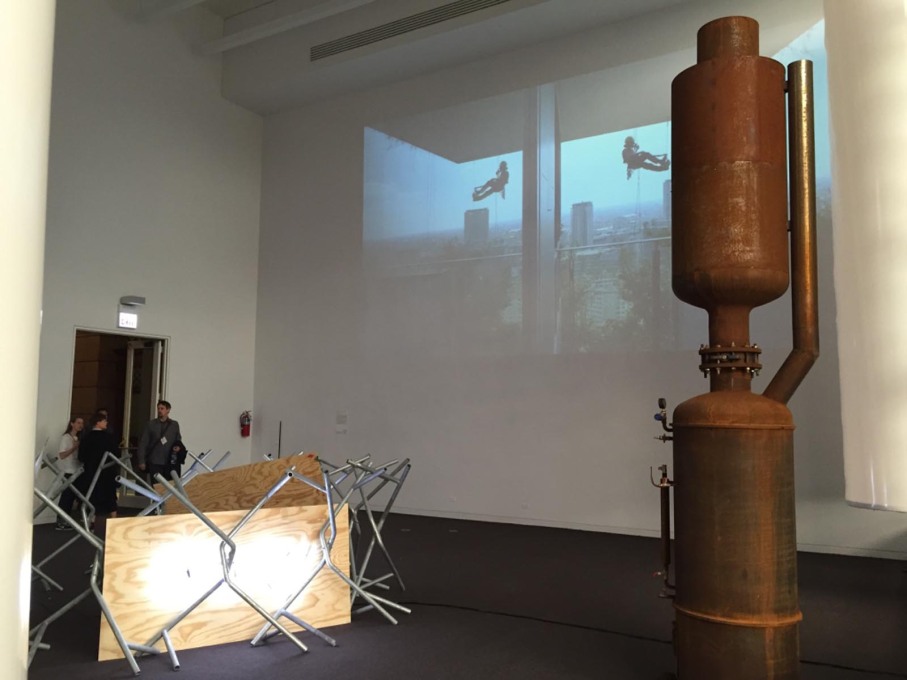

This light touch theming and cross-referencing in the exhibition continues in many of the gallery spaces. For instance three interconnecting rooms include exhibits ranging from a prototype by BIG and realities:united of their steam ring generator, designed to sit in the chimney of a power station, blowing a “smoke ring” every time a tonne of CO2 is burned: a kind of pollution-watch symbol. Looking like some antediluvian rusted cylinder from a disused factory, it contrasts nicely with the weird grey figurative tower of Gramazio Kohler, one created using the very latest in technology – being the first structure built by robots using only rocks and thread.

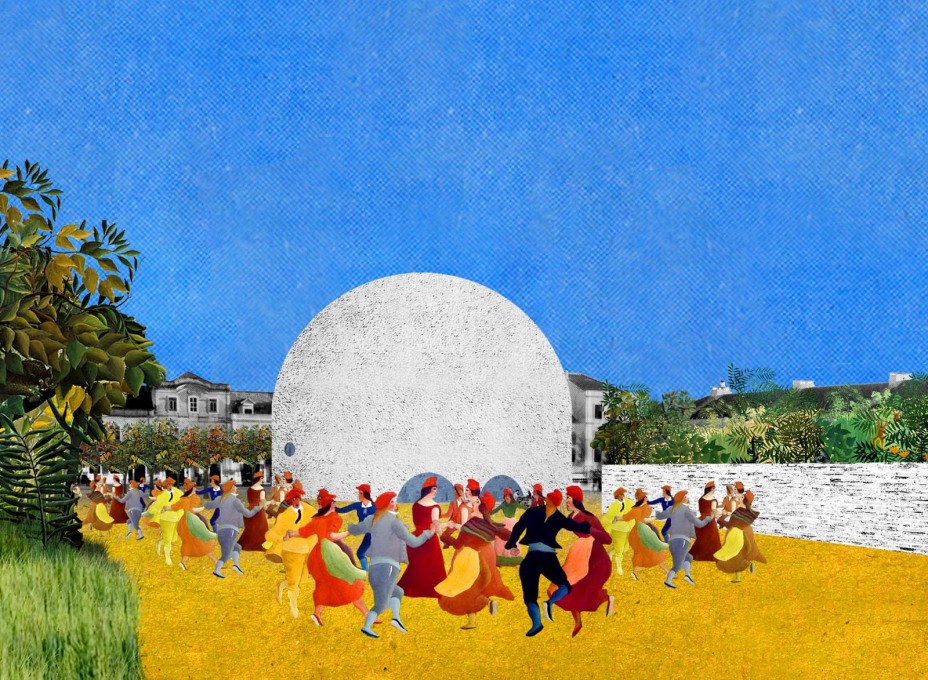

Nearby another similarly scaled tower-like structure is the model of Kuehn Malvezzi’s House for One project in Berlin, a multi-faith house of prayer, represented here by an smooth white polystyrene modelling of its interior spaces, topped by a Boulléean cylinder, its platonic shapes echoed in turn by the abstracted dome of Fala Atelier’s public library project for Setubal in Portugal, shown across the gallery space.

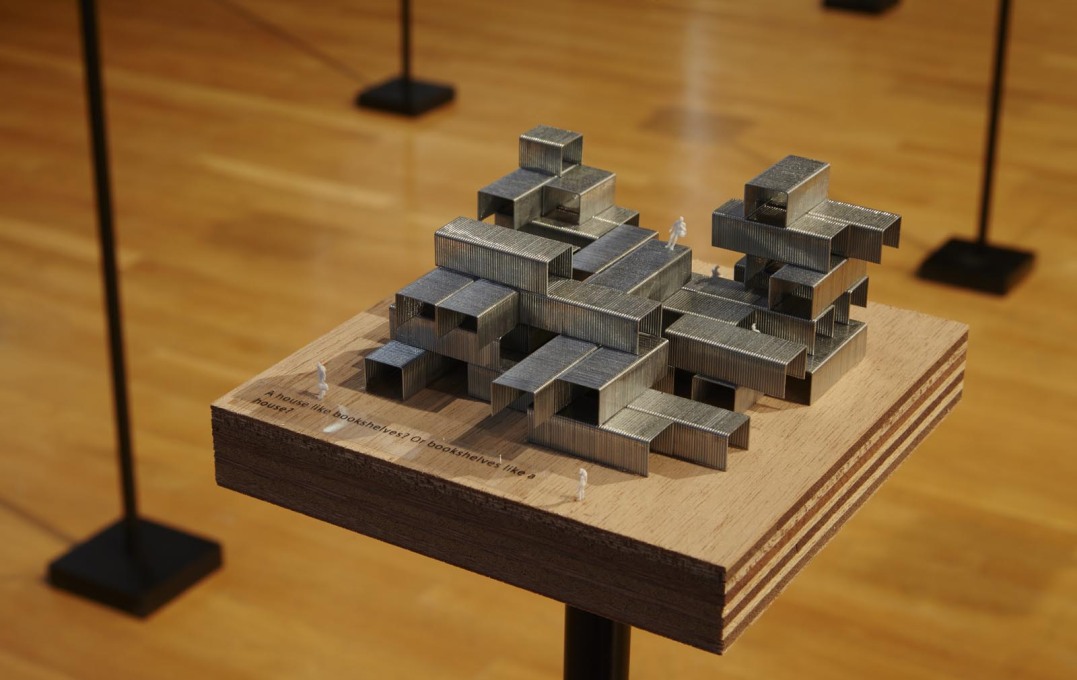

Elsewhere the focus was on strategies for managing change in communities. For example: a model of Rural Urban Framework’s toolbox of solutions for dealing with the pressures of rapid urbanisation in China placed next to Rua Arquitetos’ beautiful timber model that is used to focus discussions with the local community of a Favela neighbourhood in Rio de Janiero on changes and improvements to their intense urban environment. Meanwhile adjacent to this, PRODUCTORA show a practical example of a strategy for reuse with the boutique hotel they designed cleverly reoccupying parts of a large abandoned and ruined tourist hotel in Mexico.

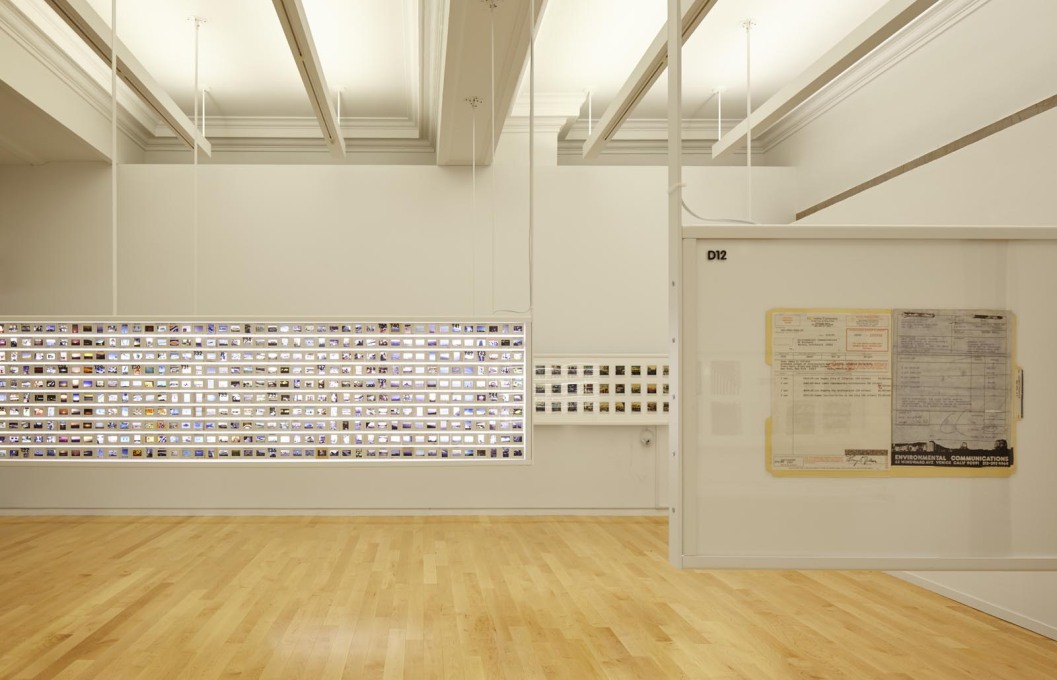

The focus pans out further with the inclusion of projects looking at wider geographies such as the legacies in the landscapes of industrialisation seen in the research work of Counterspace, who zoomed in on the communities around the open-cast mining pits in South Africa in a series of powerful images; and the questioning of geo-political constructs and how we view the world in Fake Industries Architectural Agonism’s installation of 4,000 images from the Indo-Pacific region, resetting an idea of the world from a Western- or China-centric perspective.

As Grima underlined in his introductory speech, one thread that the curators do admit to in their selection is the continued importance of drawing for many architects as a tool of speculation. Examples ranged from the very literal, intricate Mang-esque capriccios of Korean architect Moon Hoon to more speculative ideas of drawing – such as Los Angeles-based Besler & Sons’ meditations on the permutations and possibilities of the standard elements and fittings of the steel-stud partition wall, presented as a type of drawing practice.

Other more fantastical exhibits referencing forms and means of representation include Andreas Angelidakis’ Bibelots 3D printed maquettes of ruinlike structures, generated from scans on an iPhone app.

More practical concerns were also graphically on display in Studio Gang’s investigation of the changing forms of US police stations, having a cogency given recent domestic tensions there between communities and the police. Other Chicago-based practices and projects were unnecessarily corralled in a grouping of “local” projects. Several of these look at density and infill: from David Schalliol’s studies of Chicago’s inner suburbs, familiar images of isolated houses in abandoned lots familiar from images of Detroit but seen across many Midwest cities, to urban-scale interventions along the shoreline of Lake Michigan.

In total though, the very eclectism that succeeds in giving a global snapshot of “The Art of Architecture”, means the themes and cross references do not add up to being greater than the sum of their parts. This is not helped by their being encased in such a vast, gaudy building, the Brobdingnagian bones of which made everything it contained, even full scale housing mock ups, look a bit fey and flimsy. Even large installations such as the complexity of ladders and platforms of Atelier Bow Bow’s Piranesi Circus in the inner courtyard lost their power against the far more Piranesian intricacies of the Center’s interior

In any case, this installation remained inaccessible, not energising the dead space at the centre of the building but looking more like a lifeless vitrine. Other similarly visceral, experiential interventions in the building seemed to be have been shrugged off by it, no doubt stymied by health and safety concerns, including BIG’s original proposal to have their smoke ring generator actually functioning on the roof. Only a clever, but far more passive intervention, shifted perception of the fabric of the building itself. This was Norman Kelley’s Chicago, How do you see? which used large vinyls of generic window-types or famous glazing patterns from around the city, pasted over the Cultural Center’s own windows, to literally change its eyes to the city. Otherwise, everything in the exhibition felt somehow unpoliticised, removed, uncharged from the everyday.

Even the main off-site project of the winning architect-designed kiosk by Ultramoderne, the first of several intended to replace the old hotdog and soda stands that dot the lakeshore, seemed more like an art installation. The winning design is a very beautiful wooden homage to Mies, with a floating roof over which, from a viewing platform, the horizon of downtown Chicago and the lake hovere. But in scale it is more like a huge pavilion than a kiosk, the space under its roof not a practical place to linger given the lack of walls to break the insistent wind.

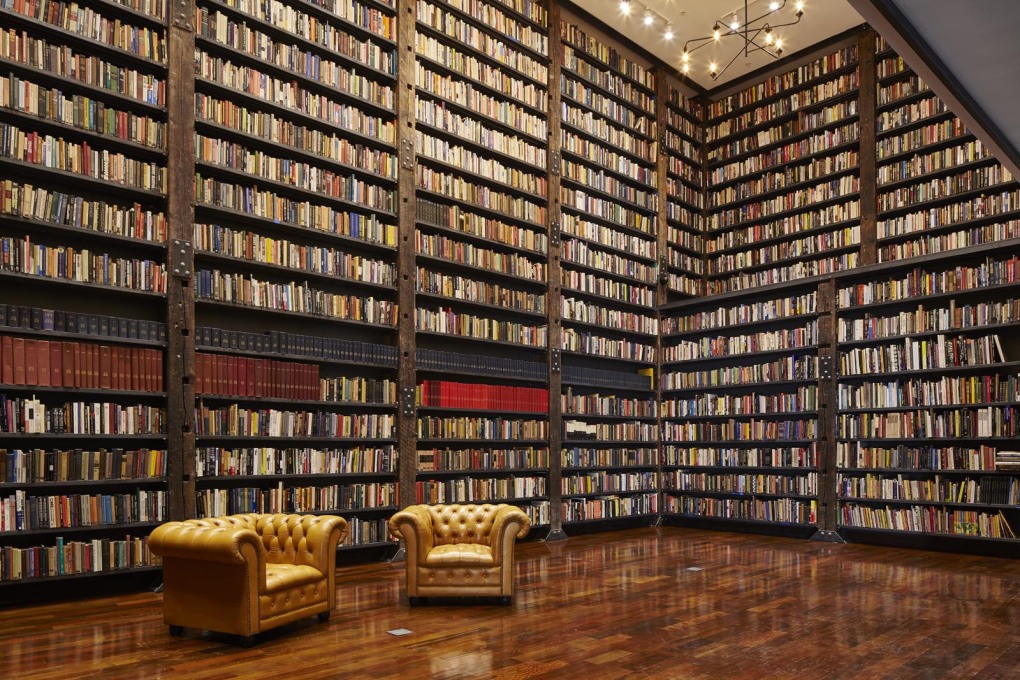

And equally across town, the impressive conversion of a derelict bank into a community art space by the artist Theaster Gates, felt more like a hipster bar conversion, with the carefully preserved distress of its interior, appearing to provide an unlikely, slightly precious, facility for its future use as community art space.

One off-site work was an exception, the performance, We Know How to Order, conceived by Bryony Roberts, choreographed by Asher Waldron, and performed by the South Shore Drill Team: a mesmeric, pseudo military parade-like performance, seeming directly to engage with Mies van der Rohe’s surrounding architecture in the downtown Federal Plaza in which it took place.

The State of the Art of Architecture provides a fascinating collection of snapshots but remains a collection none the less, too diffuse to be saying anything despite attempting to tick all boxes from the pragmatic to the fantastical. Perhaps this was due, as Sarah Herda admitted, to the curators’ intention to set up more of a template for future Biennials to build on and grow from. So while the rich content was witness to the seasoned eye of the curators in its selection, it somehow lacked a curatorial heart.

The State of the Art of Architecture

Chicago Architecture Biennial

Until January 3, 2016