William Kherbek visited the exhibition Palladian Design: The Good, the Bad and the Unexpected at the RIBA Architecture Gallery in London for uncube and found a meditative set of reflections and tensions in a calming environment designed by Caruso St. John.

“Oh dear, I think I am becoming a god.”

These are reportedly the last words of the Roman Emperor Vespasian. One can understand Vespasian’s trepidation, for an emperor to become a god, he had to die. Death, these days, does not guarantee immortality, not even for emperors – even saints have to wait until they perform a miracle or two from The Beyond to be officially canonised. Perhaps the best a master of contemporary architecture can hope for, as she slumps over her drafting board for the last time, would be to utter the final words: “Oh dear, I think I’m becoming an adjective.” Even this hope seems rather remote given that, as the press materials from the exhibition, Palladian Design: The Good, the Bad and the Unexpected, note, the only architect to have achieved that status to date is the man born Andrea Di Pietro della Gondola, known to the world as Palladio. The current exhibition at the Royal Institute of British Architects in London explores the ways in which his ideas have been interpreted over the centuries and how the name Palladio went from being a causally dispensed nickname to a style architects from Italy to Russia to the USA and beyond have sought to integrate into their own creations.

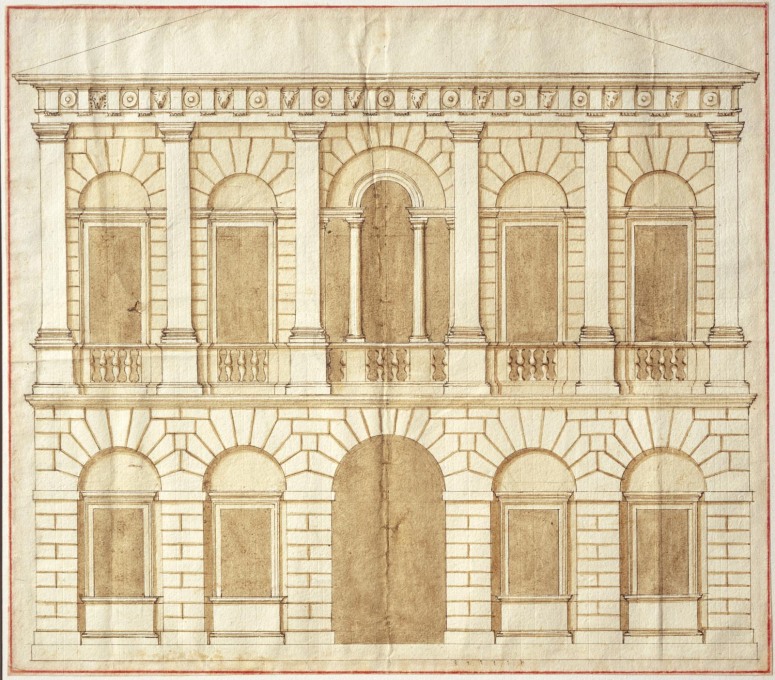

The exhibition does a good job of tracing the influence of Palladio’s I Quattro Libri dell’Architecttura as they made their way from Italy across the Channel. On show are seventeenth century designs by Inigo Jones for a version of Queen’s House in Greenwich as well as a “buttery” for Cobham Hall in Kent. The exhibition also includes a copy of an edition of I Quattro Libri from the collection of Richard Boyle (better known in architectural circles as Lord Burlington) bearing the owner’s signature on the title page.

The exhibition is keen to stress the way Palladio’s ideas infused designs for butteries and barns and cowsheds, but, of course, Inigo Jones also brought his Palladian tendencies to the design of institutions of power, as seen in the view of Jones’ Banqueting Hall at Whitehall Palace in the exhibition. It is in this tension, between the ideals of Palladian architecture and its status as the default reference point for the design of institutions of power that the “Bad” of the exhibition’s title is perhaps most manifest.

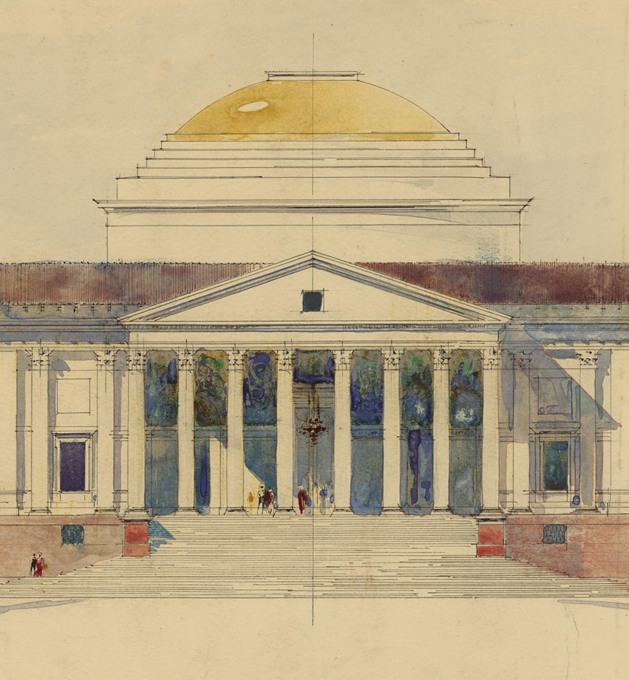

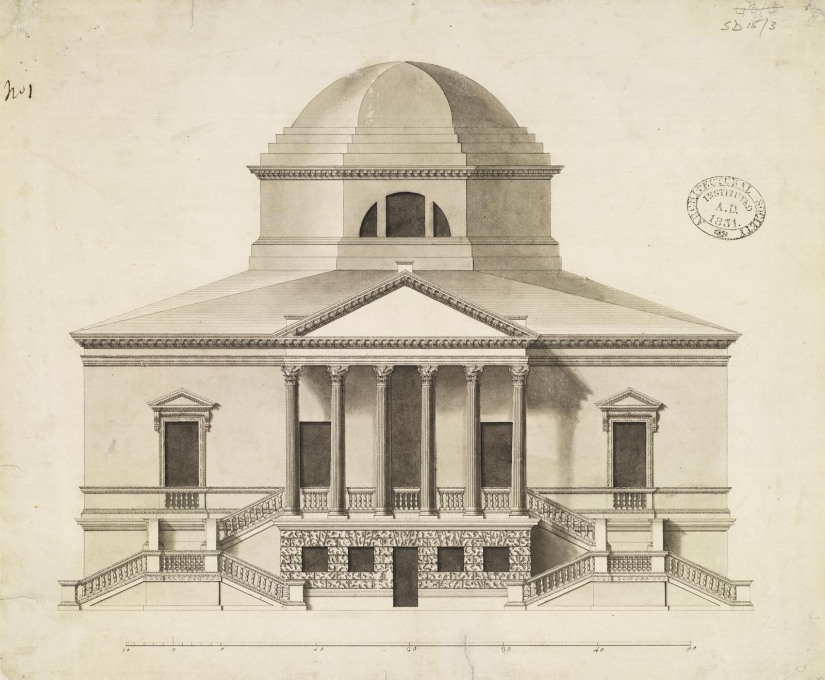

The symmetries and classical references Palladio included in his work were too appealing not to be appropriated by the builders of capitals and parliaments in the ensuing centuries, seeking a timeless and ordered aesthetic. The exhibition offers images of a number of the more incongruous expressions of Palladian influence. Among the most striking is an elevation of Sir Edward Lutyens’ preliminary design for the Viceroy’s House in New Delhi. Here, democratic principles at work in Palladio’s philosophy were to be put at the service of colonial domination. Wisely, the final version of the house paid greater respect to the Islamic and Hindu classical design traditions of the country itself; a rather more Palladian approach than simply airlifting his design principles into the colonies and demanding the “natives” respect them.

The simplicity of the design principles articulated in i Quattro Libri are the aspects of Palladio’s thought which, the exhibition stresses, have survived the various Year Zeros that Post-Modern architectural trends have asserted (and created). Palladio’s symmetries are deconstructed in a number of studies by Peter Märkli. Palladian barchesse appear in the strangest places, not least in Peter D. Rose’s St. Sauveur ski lodge. This is perhaps meant to be the “Unexpected” part of the exhibition’s title, but if so, it is a complicated argument to make. While it is true that, as a rule, you don’t think of the Portico of Octavia as being a typical reference point for a cowshed in Somerset, Stephen Taylor’s eloquent application of Palladio’s examples and ideals should really only surprise people who have grown accustomed to the kind of brutalised and inelegant design that galloping gentrification extrudes.

Whatever the finer points of curatorial quibbling, the layout of the show provides opportunity for both scrutiny and meditation. The model of James Gibbs’ St Martins-in-the-Fields at the centre of the exhibition provides a three dimensional guide to the ways in which Palladian values informed the construction of one of London’s most serenely complex landmarks. It’s the kind of work one could easily lose a few hours exploring, tracing the cut and thrust of various modes of philosophical argument its design incorporates. In quietly moving works like the illustrations by John Penn of Villas in Rendham, Hasketon, Westleton and Shingle Street in Suffolk, the potential of Palladian ideals truly shines through. Penn’s “temple-houses” are, literally and figuratively, miles from the “Statement Architecture” exemplified in the Anglo-Indian impostures; their design speaks of the possibility of an architecture for living rather than a mode of living defined by an architectural ideology. These are dwellings for people, not gods.

– William Kherbek is the author of the novel Ecology of Secrets and the forthcoming Ultralife. His work has appeared in magazines including Block, Sleek and Port.

Palladian Design: The Good, The Bad and the Unexpected

until January 9, 2016

The Architecture Gallery

The Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA)

66 Portland Place

London, W1B 1AD, UK