Once a logistics warehouse shifting goods from trains to trucks in an industrial no-mans-land, the 600 metre long Entrepôt Macdonald has been renovated into a piece of city, helping bridge the gap between the infamously isolated banlieues of the Parisian periphery and the city centre. Mariabruna Fabrizi and Fosco Lucarelli look at the transformation of the longest building in Paris and find a scheme keen to avoid the mistakes of the monster Grands Ensembles housing blocks of the past.

Renowned for its sumptuous boulevards, Hausmannian urban fabric, and sophisticated monuments, the French capital has always sold the public an image of elegance and romanticism. In popular perception, Paris has never been an industrial city. While the nineteenth century industrial revolution transformed the European urban landscape in general, in Paris Haussmann’s boulevards and avenues transformed the city centre while pushing industrial buildings and impoverished populations out to the north-east. What used to be an almost rural periphery was progressively transformed into an industrial node with large warehouses woven into a complex of canals and railways. Although huge in size, this area remained a well kept secret to tourists and Parisians alike. Even in the 1950s, Guy Debord and his fellow situationists led their “dérives” towards the northern parts of the city and referred to its landscape as an almost exotic found.

Nowadays, Paris is one of the densest cities in Europe. With a growing population, almost no free land left for development within its city limits and the progressive gentrification of previously insalubrious zones, the search for sites for new social housing is focusing on these northern, previously industrial sectors, even crossing the “Périphérique”, the huge motorway which surrounds Paris and materially defines its borders. In this complex quest for space, abandoned industrial heritage takes on a key importance. This search for new residential development sites in areas still littered with huge industrial relics that are too expensive to demolish, is generating new and unexpected urban forms with contemporary schemes having to adapt, mostly for economic reasons, to the existing condition. This formal clash between raw industrial heritage and contemporary architecture at the same time is further underlining the heteroclite character of northern Paris.

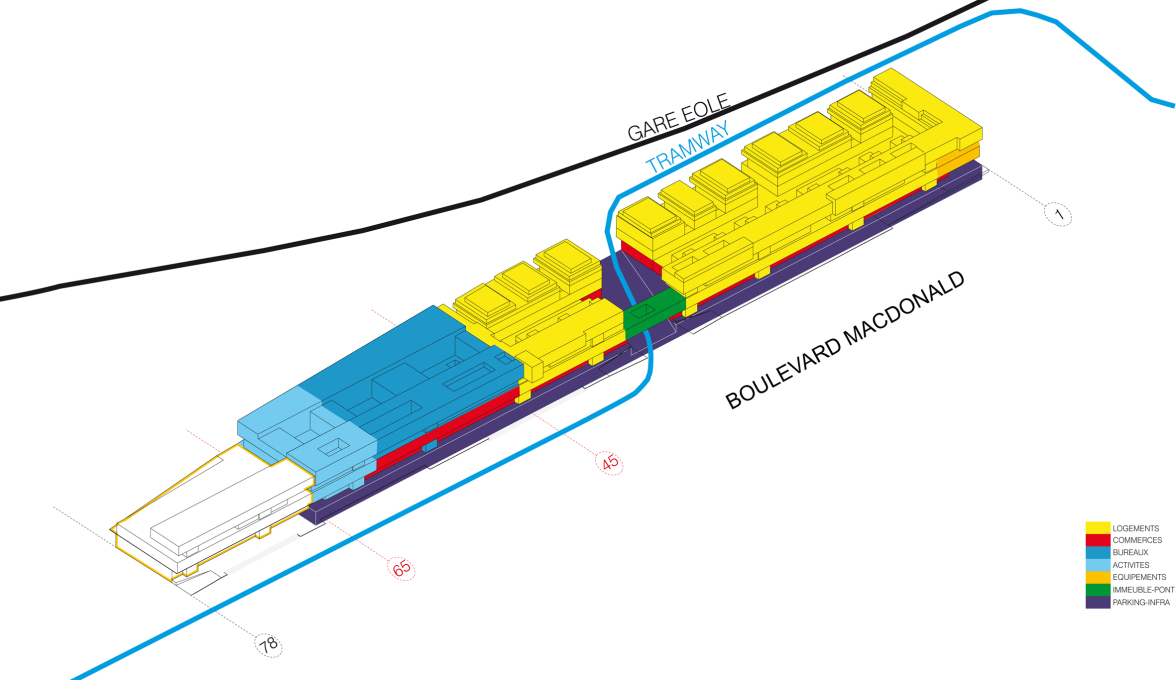

Nothing exemplifies this change better than the conversion of the former “Entrepôt Macdonald” (“Macdonald Warehouses”), into a residential megastructure, a highly ambitious programme begun in 2002 which covers almost 200 hectares of the Parisian north-east, between Porte de La Chapelle and Porte de La Villette. The 616m-long building was originally designed by the architect Marcel Forest and constructed in 1970 for the company Calberson SNTR as a logistics warehouse connecting trains on one side and trucks from Boulevard Macdonald on the other.

In order not to permanently prevent future additional mixed use of the site, the city of Paris prescribed that the warehouse be conceived from the planning stage onwards with the idea of a future development in mind. Its massive structure of concrete columns and beams was therefore designed to be capable of carrying loads of around two tons per square metre, effectively meaning it could act as a “basement-building” able to support a further four to five storeys above.

After falling into disuse, the warehouse was acquired by “Paris Nord-Est”, a company controlled by the city of Paris and the “Caisse des Dépôts” in 2006. The following year, after winning an international competition, OMA was chosen to carry out a masterplan for the conversion of the site. The programme, developed under the direction of Floris Alkemade (an OMA partner at the time) and Xaveer De Geyter, included the creation of social housing, office buildings, a school, a library and a new street, as well as a passage underneath the former warehouse; attempting – in line with the brief – to create a mixed-use “piece of the city” with a wide demographic range of users.

The position of the Entrepôts Macdonald is, in fact, a strategic one: directly on the “Périphérique”, its conversion is a key element in the “Grand Paris” project, a plan to progressively incorporate the infamous “banlieue” estates of the periphery into the city better and bridge the historical, economic and demographic gap which separates them from the historic centre. Indeed one of the risks in keeping such an enormous wall-like building is its potential to remain like a barrier, further separating the two sides.

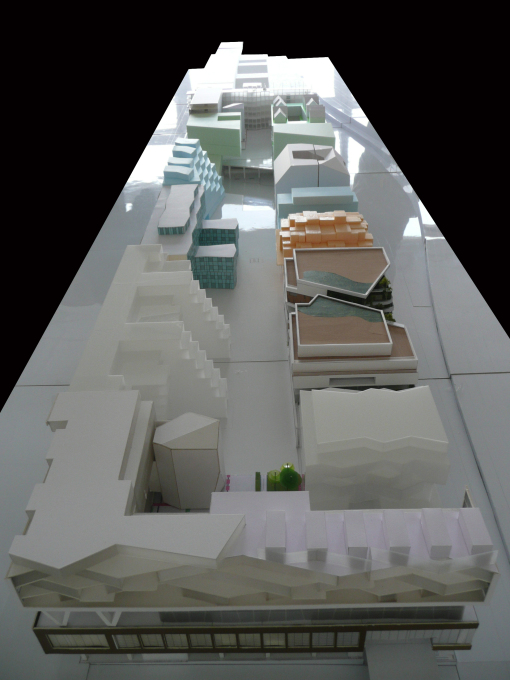

Therefore, while the horizontal character of the original platform has been maintained by keeping the line of the base facing the boulevard, a search to create porosity through the two blocks has been a priority since the beginning of its conversion, including the excavation of a large central inner courtyard and several others, which breaks down the building’s 80 metre width, making it suitable for domestic units, while creating communal spaces for residents.

Similarly, in order to avoid the monolithic look of previous housing models, a superficial diversity has been built into the ensemble, with the design of separate blocks assigned to fifteen different architecture practices. Each one, consisting of individual units, rises four or five more floors above the original slab-level of the warehouse and is independently accessed from ground level. On the main boulevard side, a single warehouse-like façade is preserved; but to the other side each of the separate volumes contributes to a varied and fragmented skyline.

The project is now faced with the challenge of mimicking the social dynamics of a neighbourhood that developed organically over time, and to avoid the fate of the infamous Grands Ensembles, massive post-war housing complexes, that were mono-functional, lacked connections to the street, and projected visual monotony. The designers of the Entrepôts Macdonald have tried to escape this by adopting a strategy of creating artificial diversity through variations in façades and volumes.

It is too early to judge if the project will succeed in inventing a new urbanity in this area of the city with its troubled history, but whatever its successes or shortcomings, it is an important initiative in a city where the increasing cost of land is equalled only by the increasing need for affordable housing.

Mariabruna Fabrizi (*1982) and Fosco Lucarelli (*1981) are architects and educators from Italy. They are currently based in Paris where they have founded the architectural practice Microcities and conduct independent architectural research through their website SOCKS.