Having tackled the merits and maladies of ornament in architecture, the Turncoats tide continues to take architectural debates by the scruff of the neck and throw them around London. Their latest showdown centred around the “conservative, traditionalist and infantilising” nature of debates on women in architecture. Pete Maxwell took minutes for uncube on The Gender Agenda.

Coming barely a week after the righting of “a 180-year wrong”, as RIBA president Jane Duncan described the awarding of the body’s Royal Gold Medal to Zaha Hadid, the first sole female winner, the latest instalment of the Turncoats debate series provided a timely interrogation of gender inequality in architecture. Hadid used her acceptance lecture to rail against those who dismissed her work as self-indulgent. Indeed, no other leading practice’s output seems to attract as many brickbats as Hadid’s does. Much of this criticism has a decidedly ad homonym flavour, especially as regards Hadid’s personality – she’s apparently too forthright, too pugnacious, somehow not as accommodating as she is expected to be. But, if we’re being frank, when have architects ever had a reputation for being cuddly? As commentator Will Wiles reflected recently: “architectural discourse has been somewhat quicker to ignore the shortcomings of its Great Men than it is for this Great Woman.”

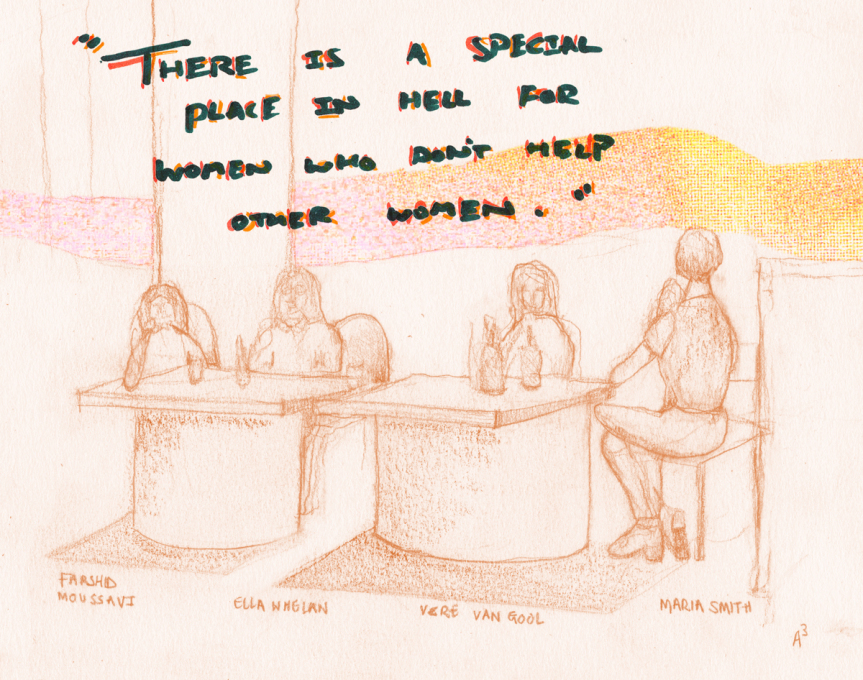

Zaha was conspicuously absent from the discussion that took place in the ground-floor event space of U+I, a property regeneration company near London’s Victoria station. In fact her name wasn’t mentioned until one of the audience members [Catherine Slessor, the first female editor of the Architectural Review] pointed out, towards the close of proceedings, that her name hadn’t been mentioned. Perhaps the organisers forbade it for the sake of difference, or maybe the four interlocutors – architects Farshid Moussavi and Alison Brooks, journalist Ella Whelan and architect Vere van Gool – felt the one truly stratospheric female architect star might exert too much gravitational effect on their individual arguments. Her evolution into both a paragon and pariah, however, acted as a useful backdrop to the ensuing discussion.

Following the established Turncoats rituals of free beer, vodka and stand-up comedy, the debate, chaired by co-founder Maria Smith, advanced upon its topic: is the current dialogue surrounding women in architecture “conservative, traditionalist and infantilising” and does it risk embroiling a generation of women in “an anachronistic gender war”?

Starting out for the Pro team, Iranian architect Farshid Moussavi, formerly of FOA and now head of her own eponymous studio, conjectured that, instead of simply attempting to “level the playing field” we might question whether “being an outsider could give you an advantage?” Moussavi flipped the argument to position herself as against “the imposition of conventions”, even tentatively suggesting that “a lack of female role models,” and thus stereotypes, “can be freeing”. Why not instead treat “exteriority as a space for creativity”?

Moussavi noted that, in a homogenous group, shared expectations of knowledge can be debilitating, preventing people from questioning core issues in case they appear uninformed – “thus silence becomes a position of compromise.”

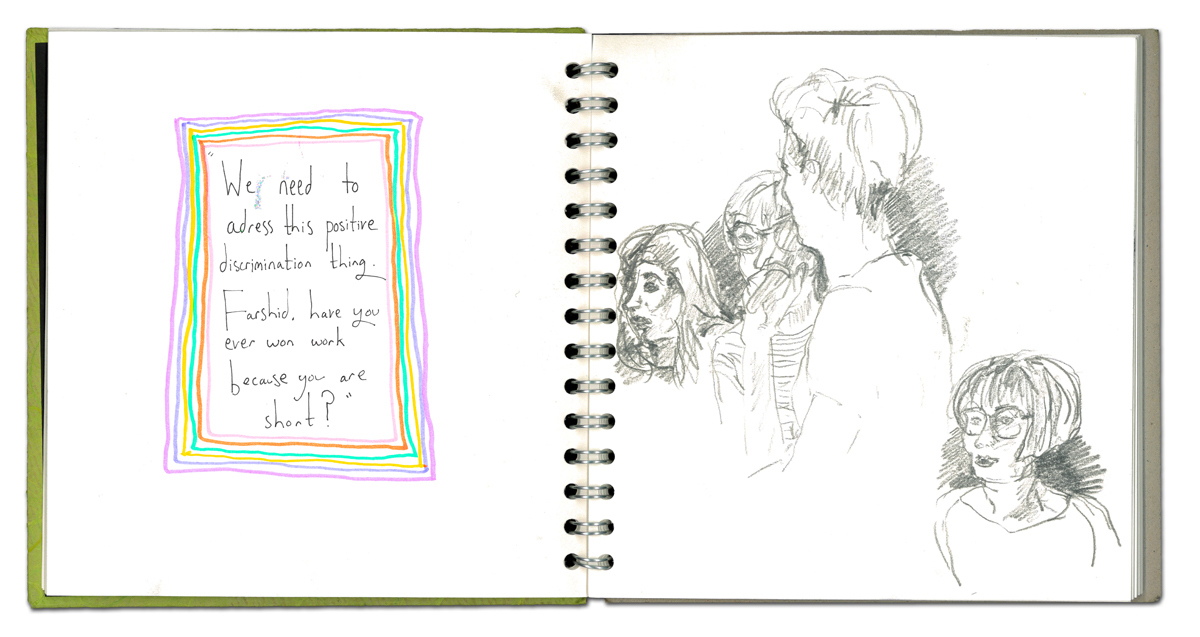

As founder of MISS, an initiative actively devoted to making space for women in the arts, Vere van Gool was certainly in opposition to the idea that there shouldn’t be more concerted action by the architectural establishment to redress the gender balance. Having studied architecture at the Delft University of Technology, where the ratio of men to women was 10:1, she knew all about the biases that can skew even the most prosaic of architectural conversations. She recalled a university project review where her work was praised and, as such, presumed to have been created by a male student. In this sort of atmosphere it was no surprise to van Gool that “just 34% of practicing architects” registered with the RIBA in 2013 were female, or that the number of women in architecture gets smaller the more senior the position. van Gool was keen that we should first highlight some of the obvious and addressable reasons behind this drop-off, such as a gender pay disparity that sees female architects earn only 83 pence to their male counterparts’ pound.

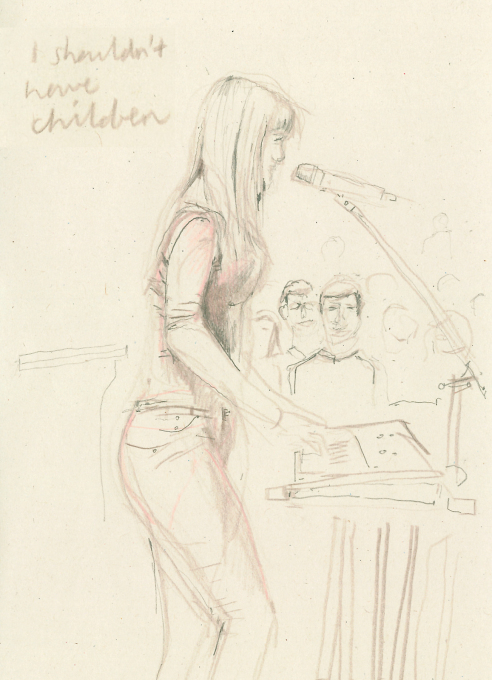

The outlier of the group, having neither worked in nor studied architecture, was journalist and free speech campaigner Ella Whelan. She used this position (partially proving Moussavi’s point) to speak vociferously against the “patronising” circuit of female-only design awards and the culture of special pleading for women architects. She countered that success through such means would amount to a pyrrhic victory. Achievement based on talent alone would be the only long-term corrective.

What’s more, women in the workplace were often framed as remedial of a male dominated office culture that is sometimes “too aggressive”, with the promotion of women often depicted as a means of somehow making the workplace “nicer”. Whelan instead argued for women to be allowed to show their own aggression, men their lightness of touch, and for such character traits to stop being segregated between the sexes. Focusing on the gender of a person merely reinforces the destructive binary at the heart of the issue. “You shouldn’t need women in high roles to in order to want to be an architect, just great architects.”

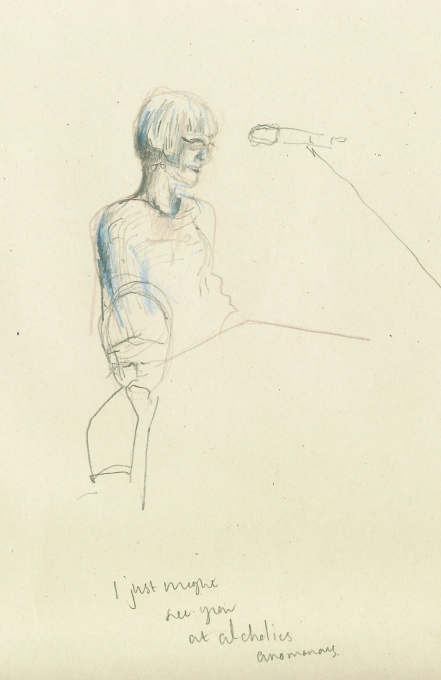

The final speaker was Canadian-born, UK-based architect Alison Brooks who, in preparation for the evening, had done some comparative research into how other disciplines worked to promote women. Unsurprisingly, architecture came a poor second. Offering case studies of initiatives such as WeAretheCity, she wondered “where are we as a profession” when such extensive dialogues were being held elsewhere and architects were not taking part. “One of the first steps to overcoming addiction is saying its name out loud,” Brooks remarked; “we need to say ‘We are not very diverse’ and, in a benign armchair socialist kind of way, are we going to do something about it?” Brooks also queried what women needed to do to force change in the workplace. She promoted “womensplaining” in the face of so much “mansplaining”, advising young female architects to be “the first to speak” and to “know your shit and know it better than the next person.”

All four panellists presented compelling arguments, which, as expected, didn’t bring the knotty issue much closer to resolution. But while it was clear that the subject of the debate was certainly not an anachronism, both Wheelan and Moussavi did a fantastic job of making the nature of the wider discourse surrounding women in architecture appear “traditionalist and infantilising”. While simply telling women to get on with it, to shine even brighter – as one audience member commented, the apprehension is that gifted women have to work twice as hard to get the same recognition as an average male colleague – would undoubtedly be negligent, as Whelan in particular reiterated, over-promoting special measures on behalf of women could be interpreted as tacit support for the notion that they make inferior architects. Do we want to convince a generation of young female practitioners that they cannot succeed without a leg up? Especially since, as it stands, when they reach the top they would still be treated so differently from “the Great Men” that are their peers?

– Pete Maxwell is a London-based freelance design and architecture writer. He is co-founder and Deputy Editor of design biannual Dirty Furniture.

Further reading: For more from the Turncoats revisit Ellie Duffy’s review of the raucous Ornament is Crime is Crime debate, or get behind the scenes with Shumi Bose’s interview with organisers Phineas Harper and Maria Smith: Fights of the Round Table.