Whilst everyone in the international architecture circus is preparing for the opening of this year’s Architecture Biennale in Venice, there seems to be another biennale coming up in a tiny village in rural China; one which could have a big impact on the nation’s building industry. The First International Bamboo Architecture Biennale will take place in the region of Longquan, about 600 Kilometres south of Shanghai. With some 18 buildings almost completed by 12 architects, the event aims to advertise the use of locally sourced materials and re-inject local knowledge into the huge machinery of the Chinese building industry. uncube’s Florian Heilmeyer met with German architect Anna Heringer, known for her use of sustainable materials, about one of the projects: her remarkable design for a truly innovative three-building hostel in Baoxi.

The site chosen for the International Bamboo Architecture Biennale seems to be in a really remote village called Baoxi. How do you actually get there?

The closest international airport is in Shanghai. From there it’s about a seven-hour drive south by car or bus until you reach Longquan City in Zheijang Province which is the nearest big city. From there it’s two more hours along smaller roads until you get to Baoxi, a small village surrounded by mountains and bamboo forests. It is a quite beautiful landscape and the towns and villages one passes have a notably long history. For thousands of years people have been building there with local materials like stone, bamboo and rammed earth.

Unfortunately on the way there all you see is concrete. From the motorway you look at giant towns with monotone slabs of it, one after the other, after the other. So on this nine-hour ride from Shanghai to Baoxi, you can easily reflect on the dimensions and changes of the building industry in China. You could, for instance, think about this unbelievable statistic: that China consumed more cement in three years from 2011-2014 than the US did in the entire twentieth century.

Holy moly!

Holy moly indeed! But the issue is not only about concrete as an unsustainable material, what is really depressing is that these housing blocks all look the same until you approach the village; the road leads up and down and up and down through green hills and along little streams to Baoxi. It is such a rich landscape: the bamboo forests are thick and the earth is heavy and thick too. I always check the landscape for building materials and here I immediately noticed that it is all already there. The earth and the bamboo are fantastic building materials.

How did the Biennale come to this small village?

The initiative came from a local artist, Ge Qiantao, who is curating the event together with the architect George Kunihiro. In 2013 they invited us to come here along with 11 other architects. They introduced us to the site and the village – and to their ideas about how to demonstrate the relevance and beauty of bamboo as a contemporary building material, especially in contrast to the heavily standardised routines of the Chinese building industry.

All of the invited architects had a reputation for sustainable architecture. The names include Chinese professionals like Li Xiaodong or Yang Xu as well as international offices like Kengo Kuma, Keisuke Maeda (both Japan), Vo Trong Nghia (Vietnam) or Simón Vélez (Colombia). In the end, 18 projects were conceived together with partners from Baoxi.

Have any of them been completed yet?

As far as I know, all of them will be completed later in 2016. Then the Biennale will finally be inaugurated and hopefully they’ll manage to repeat it every two years in different locations in China. These are quite unusual structures and the buildings include houses, ceramic workshops, hotels, restaurants and a ceramics museum, but there is also infrastructure, such as new bridges, made of bamboo. All the structures are meant to strengthen handicraft traditions or to attract tourists to see this traditional side of China. It is really not easy to get such an ambitious project going in such a remote, rural environment, also because “biennale” in this case doesn’t mean that it is just a temporary event, but all buildings are meant to be permanent.

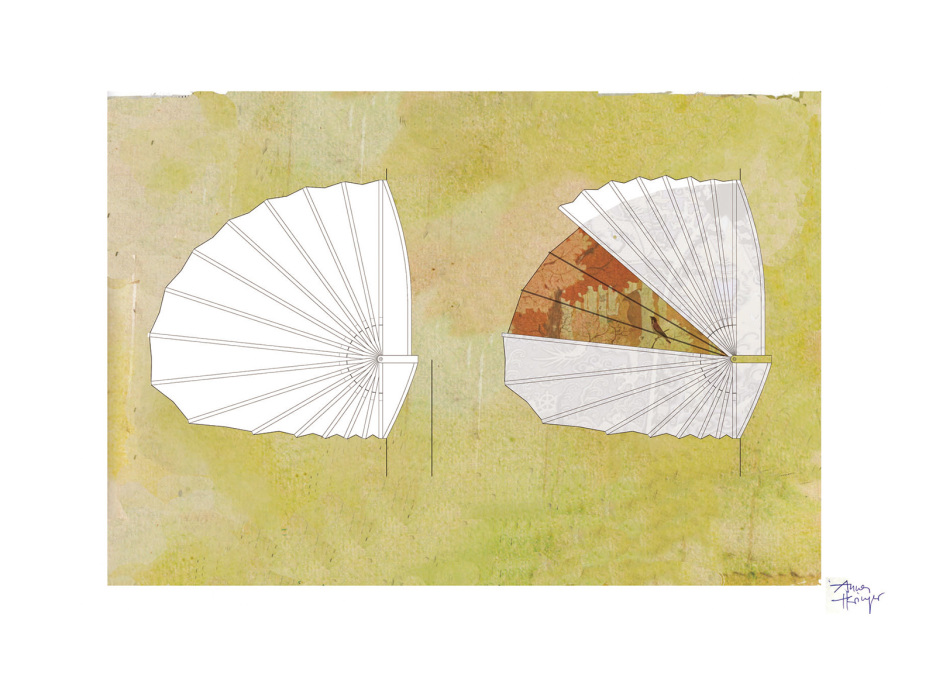

How did you develop the particular form of the hostel that you’ve designed?

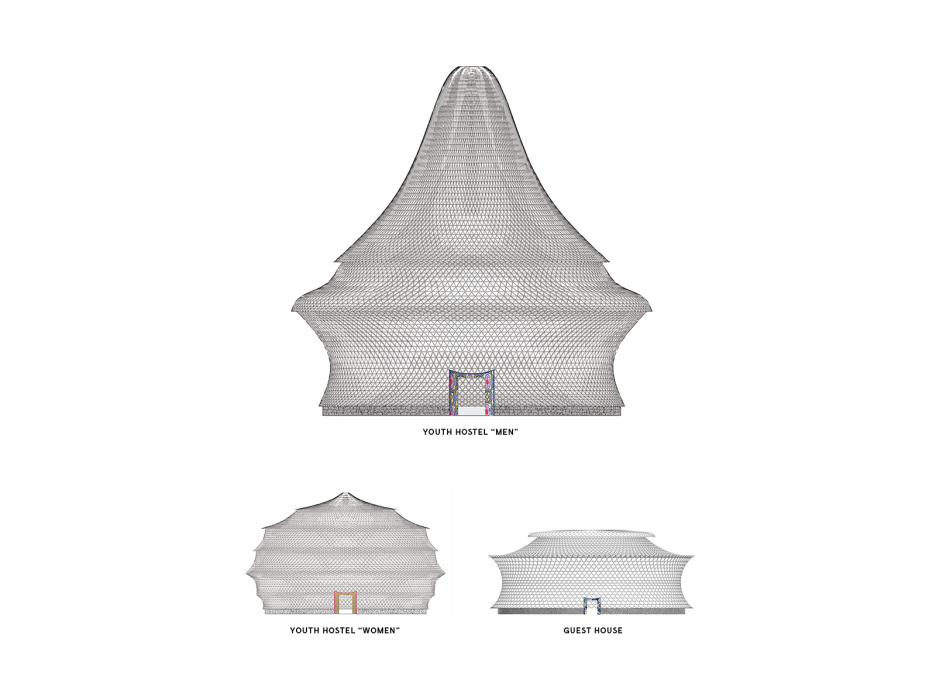

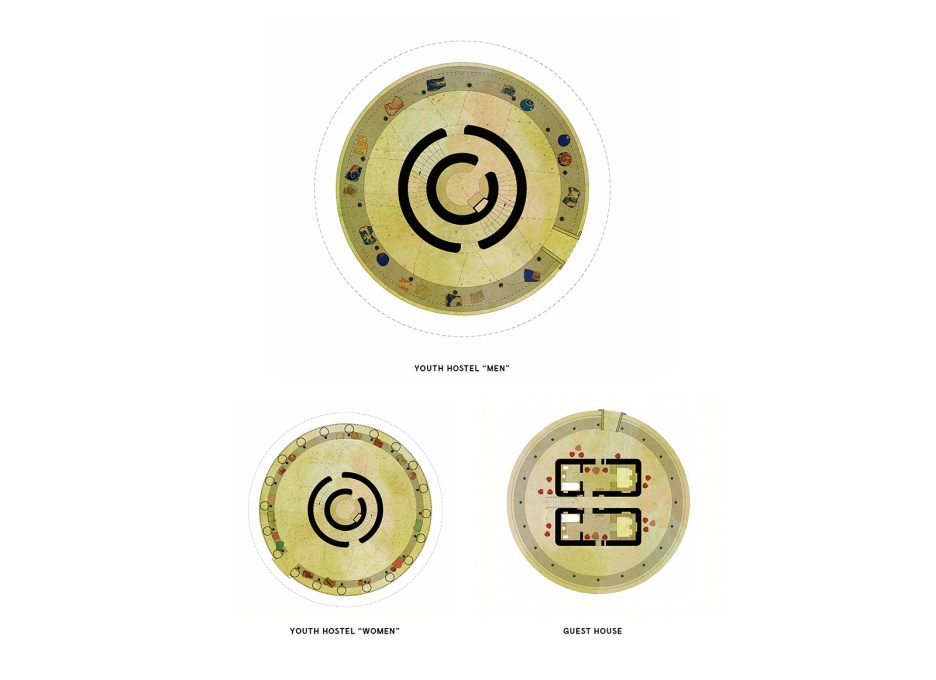

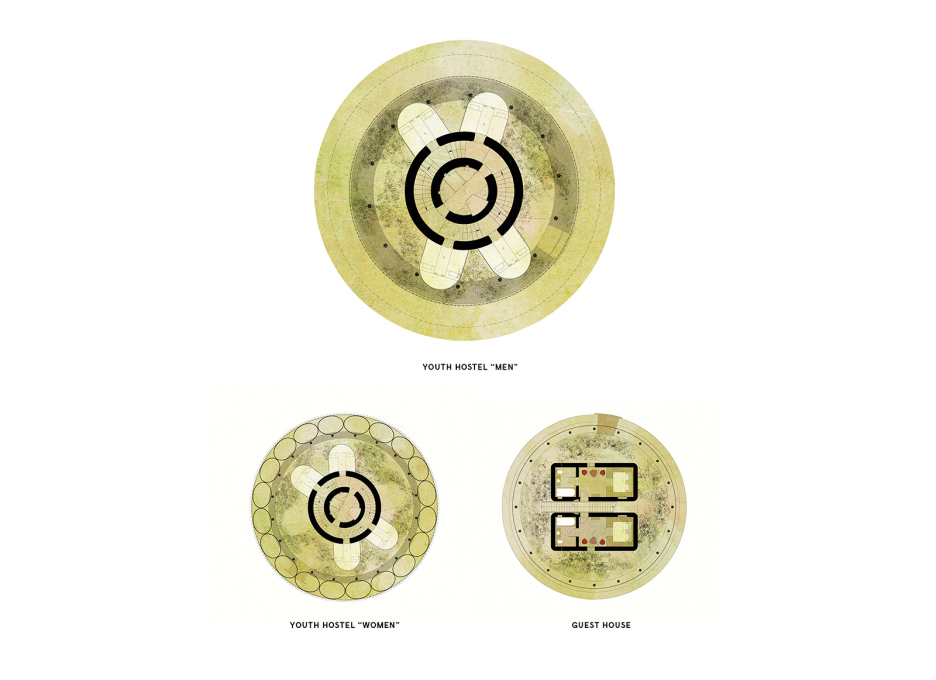

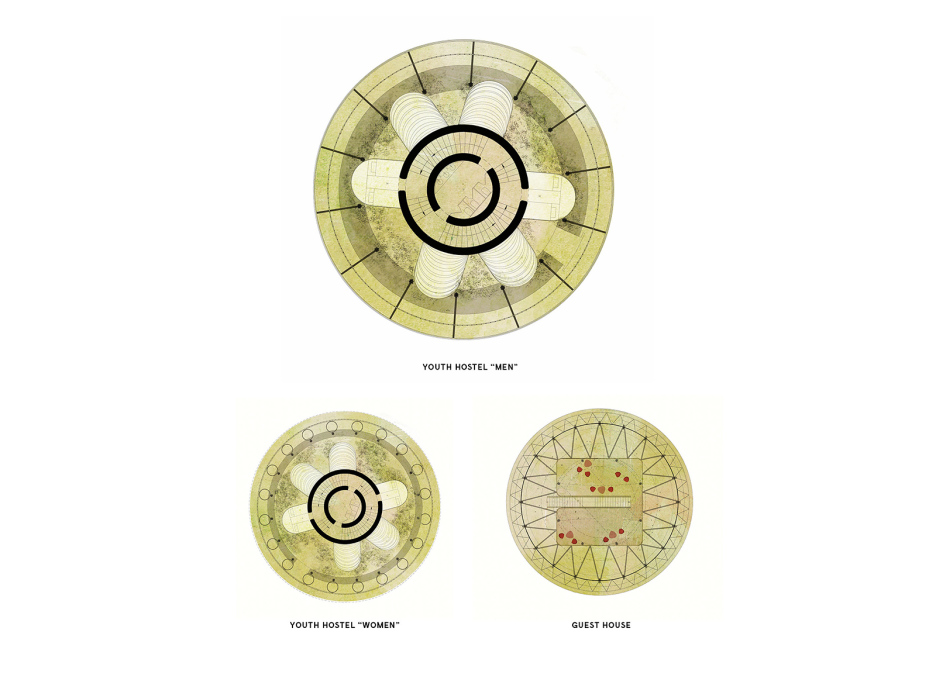

It was an intuitive decision taken on my first visit to Baoxi. After walking around the village I thought that the hostel needs to be a small structure. So I divided the programme into three separate buildings and decided they should all be like big objects. The tradition of ceramics and basket weaving is very present in the village – there are workshops everywhere that stack their products and goods outside. So the idea was not only to use locally sourced materials like bamboo and rammed earth, but also to create something that connects as an object and as a form directly with these handicrafts. Coincidentally I had also been doing a lot of ceramics the year before in Harvard, trying to learn the technique just privately for myself, so I guess that has also influenced the three buildings a lot.

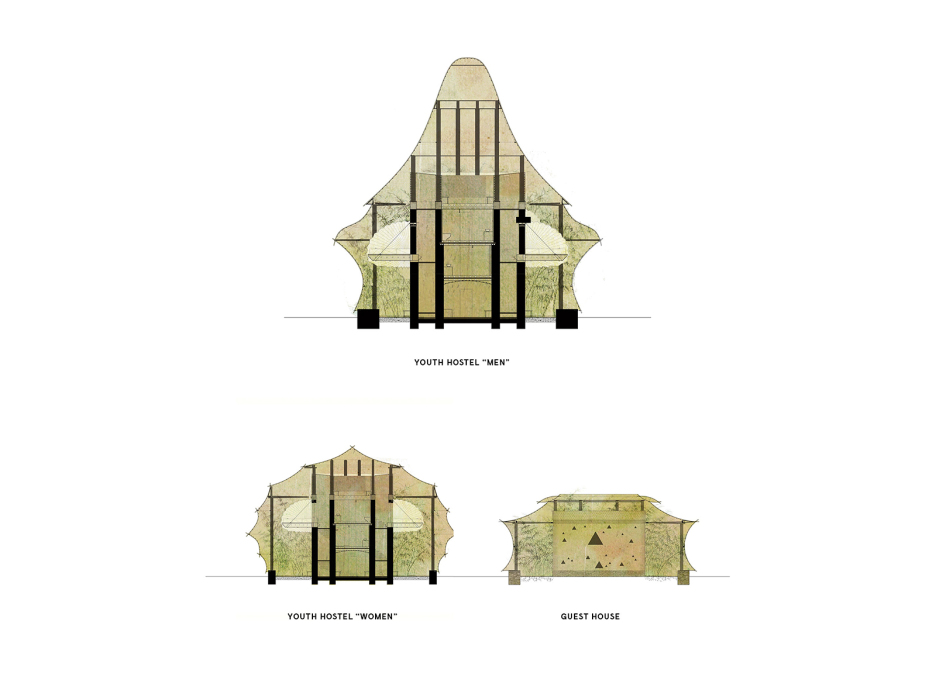

Indeed, the three buildings look a little like clay pieces formed on pottery wheels.

As an architect, I have never worked with round forms. I developed the basic idea and forms in Baoxi, then I started to discuss how this could actually be built with local craftsmen – which turned out to be surprisingly simple as they are very open-minded and their abilities are absolutely fantastic.

So it’s not only about using local materials, but also about keeping traditional building techniques alive.

Exactly. But it’s also about developing them, about creating new ideas with old techniques. They had never “woven” an entire building before. But one of bamboo’s main qualities is that it is strong and very flexible at the same time. That was something that has always interested me, to do some “weaving” with the bamboo. Finally this biennale offered an opportunity to try this.

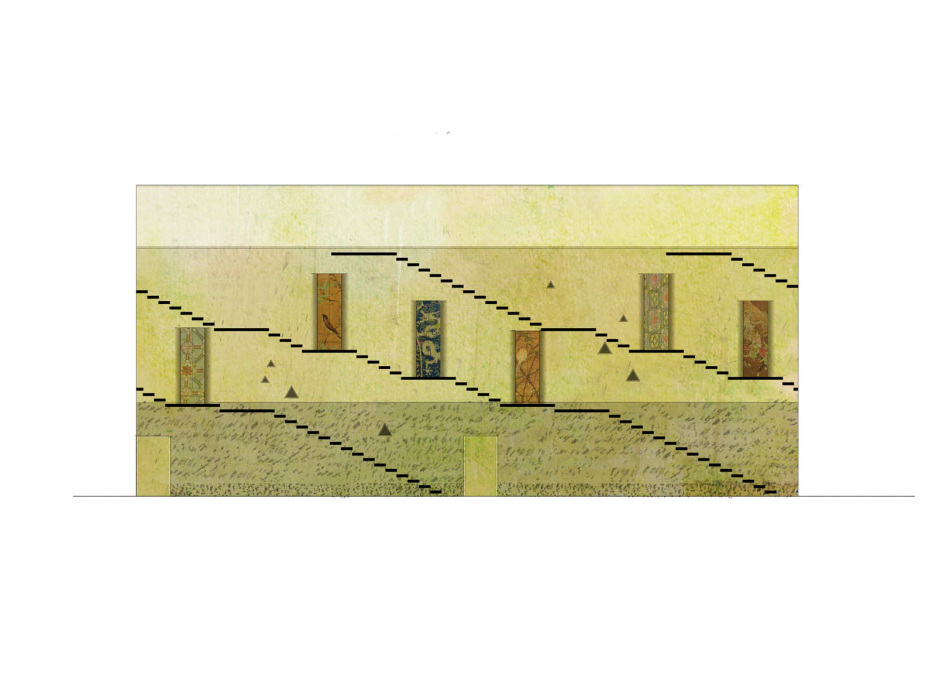

With the open bamboo structure around a solid core of rammed earth and stone it seems like a highly experimental project. Guests of the hostel will be sleeping on platforms that are hung from the building’s core, within the bamboo basketwork, covered only by tent-like capsules that glow at night like the famous Chinese lanterns. How did the residents of Baoxi react to this proposal and all its symbolism?

They reacted very nicely, very openly and were full of ideas for how to help construct the project. They only had a problem when I named the three houses “the nightingale”, “the peacock” and “the dragon”, adding some symbolic layers to their forms. All of a sudden everyone seemed to be confused and reluctant since the dragon is such a very powerful symbol – it just seemed to be too much for that building, so I don’t actually know if we’ll still call it that.

However, the organisers were enthusiastic because the construction was very direct, simple and hands-on, so they could involve some untrained workers from the area. With most buildings in China you always have to get one big company involved that manages the construction site with their own team. This way, all profits made from construction are hardly ever shared with the local communities. It became a crucial part of our strategy to demonstrate that building can be organised in a very different way; in a way, this is a much more “socialist” way of building since the residents of Baoxi benefit from the profits as well.

Everyone (involved with the Biennale) has also agreed that in order to escape the concrete monotony of the Chinese building industry, it is absolutely crucial to involve locals much more with designing and thus forming the future of their own communities again – which basically just means reminding them of their own traditions, which were destroyed or at least severely damaged by modernism. Yet at the same time it is not about being nostalgic. These traditions need to be updated in accordance with the knowledge and the techniques we have today.

What effect would you like to imagine for this group of rather small-scale projects, which are being promoted as pilot projects for bamboo buildings in China, to have?

It is true that in China everything is so big, so fast and so loud that it is difficult to make a difference with such small buildings. That’s why we have to announce them a bit louder, because the idea is of course to make them all examples of how to build poetically, simply and effectively at the same time. I would hope that the entire project can help to demonstrate the beauty of natural materials and the appeal of non-standardised, individual and very local solutions in order to enrich the culture of China’s contemporary architecture. I also hope to foster fair economics by involving the local community in the entire project; from the design to the construction to the operation of the buildings. Finally, I would like to advocate ways of building that preserve our planet’s eco-system. As an architect I like to think that whatever I build, I have to multiply it seven billion times in my head and ask myself: is this really contributing to more equality and diversity on this planet?

– Interview by Florian Heilmeyer

Anna Heringer is a German architect based in Laufen. Her work focuses on the use of local materials, skills and energy sources to create buildings that are distinct yet contextually connected to their surroundings. For her METI Handmade School in Bangladesh she won the Aga Khan Award. She will participate in Alejandro Aravena’s main exhibition at this year’s Venice Architecture Biennale. anna-heringer.com

International Bamboo Architecture Biennale: bamboocommune.com

Further reading: For more on identity and context in contemporary Chinese archictecture, revisit Rob Wilson’s interview with Zhang Ke of standardarchitecture: “Architects also need to think, right?”