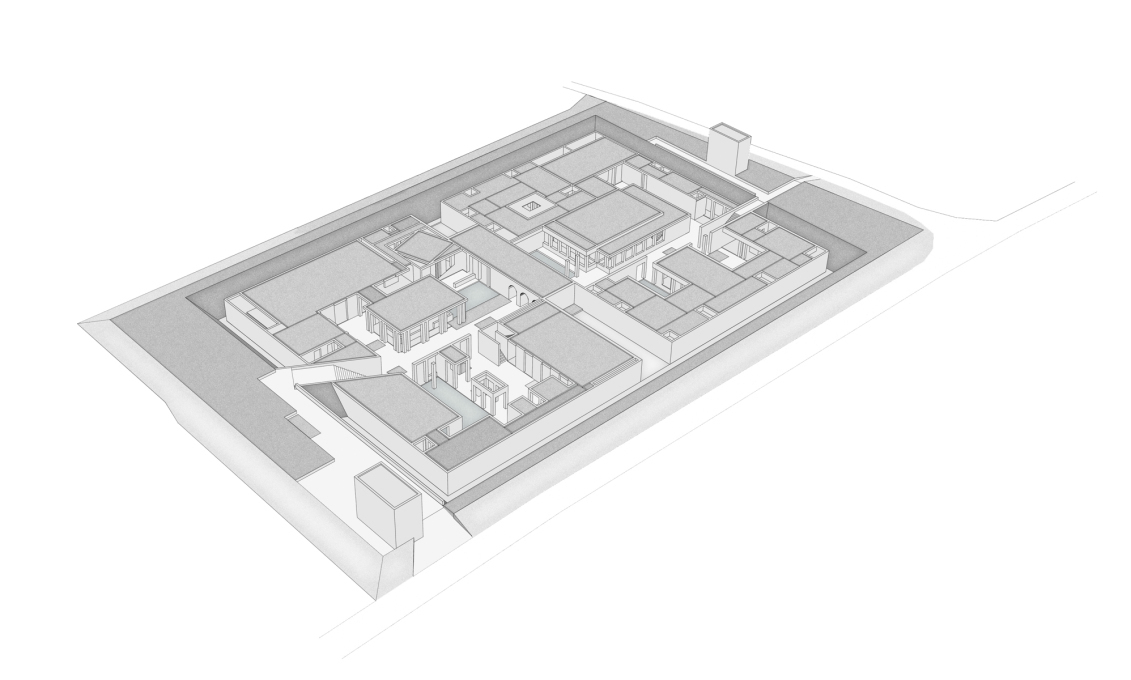

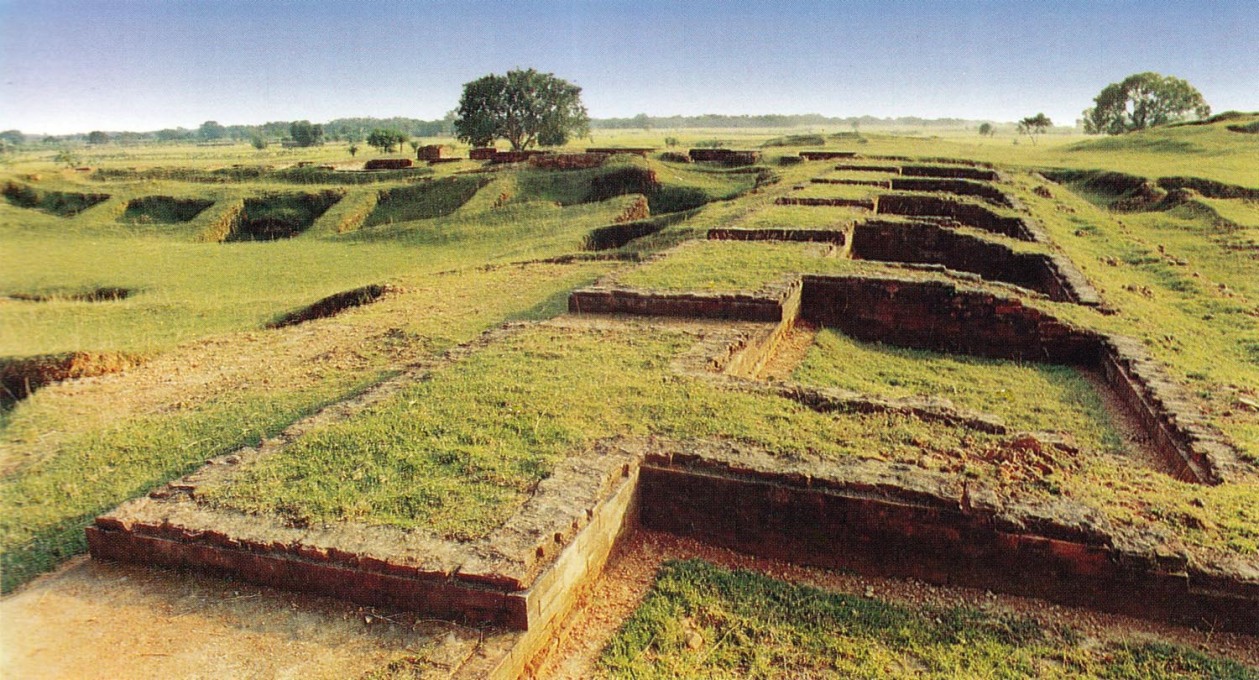

Nestled in the flatlands of rural Bangladesh near the River Brahma-Jamuna, coursing down from Tibet, flush with the silts and melted snows of the Himalayas, the Friendship Centre is one of those new buildings which feels as though it may have been there for a very long time. Whilst the simple, graphic forms of its brick construction present a slightly archaic aspect, its enclosure by a bund or embankment lends the whole site an inward-looking inverted feel, almost like an excavation. This sense of history and rootedness is a central one in the work of the Centre’s architect Kashef Mahboob Chowdhury and his practice URBANA, with its forms and plan drawing on influences from Louis Kahn to Buddhist monasteries. We asked him about the project and its genesis.

The project has a pretty unique brief. How did it come about?

The client, Friendship, is an NGO that works with those living in the remote riverine islands of the region. Their programmes, including health, education, capacity building and women empowerment, are targeted at some of the poorest people in the country. They had this idea for a centre which could be used for training sessions, classes and meetings and also as a facility they could rent out as an income generator. We wanted to take this idea further and truly create a centre, around which the activities of this wonderful organisation would revolve, but that could also serve as a place which brings people together. In this way, the architecture needed to be simple and bare: a response to the economy of the region, and with a quality of calmness and serenity that echoes the nature of its riverine landscape setting.

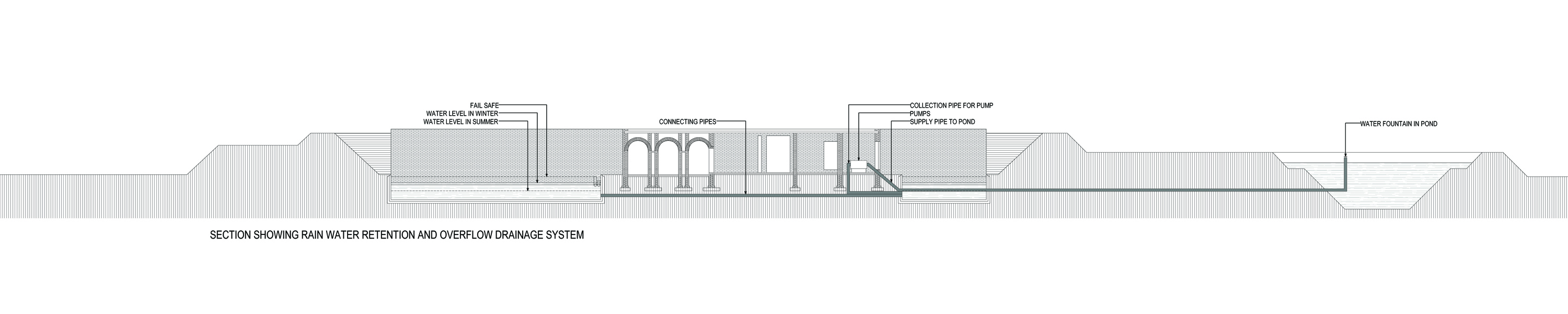

The building's immediately distinctive feature is its surrounding bund, which provides flood protection. What were the factors – environmental or budgetary – in the decision to use this? Does it have local precedent?

Bunds are not uncommon in the region but they are constructed for protection of large areas or entire districts as opposed to a single complex. The client's brief was quite extensive but the budget they had was very low. So after coming up with a design, our estimates showed we were spending three quarters of the budget on earth fill, foundations and the structure needed to raise the entire complex by eight feet – above the highest recorded floods. Therefore in the final design, we decided to build directly on the existing land itself, with the complex protected by an embankment, which could be constructed and maintained at a fraction of the cost of the original plan to raise the whole building.

Louis Kahn, whose work I know you admire, talked of an “architecture of the land”. This building appears literally to be that – almost like an excavation because of the surrounding bund. Could you comment on the importance you see in rooting a building in its context?

In Bengal, land is referred to as 'Ma' or mother and a deep emotional relationship can be felt between the land and its people. But there exists other clues elsewhere: the French have a word 'immeuble' which as an adjective which means immovable. But as a noun, it means building. Now, there lies the true nature of architecture, that is, if architecture is an art, it is an immovable art. Therefore unlike other art forms, like painting or film, architecture is forever married to the place where it is located: to its climate, its flora and fauna. And to its people. In my work I know of no greater need than to 'root' an architecture and let it 'grow', or merge and settle in its context.

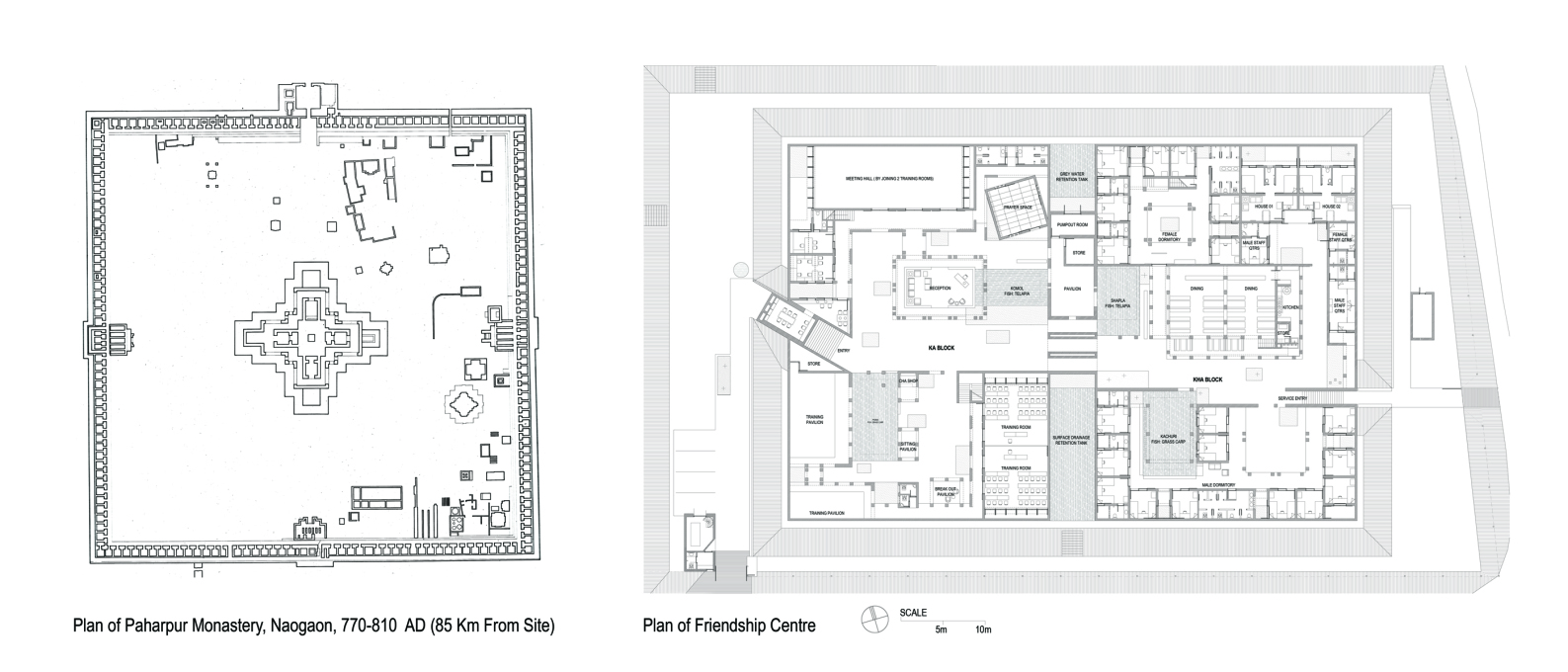

Because of the bund, the building's plan seems to function more like that of a walled town – looking inwards with its outdoor spaces as a series of courts. Knowing your work draws on history and precedent, I was wondering if you could talk about the models you looked in developing this layout.

Two thousand years ago, this region was predominantly Buddhist and therefore it has many ruins of Buddhist monasteries, which influenced the design. I have always been fascinated by ruins, including the image in my mind of Kahn's National Building in Dhaka, work on which remained abandoned for many years. For a child growing up and passing by that construction site everyday, it was the most beautiful of all ruins. And like those of ruins everywhere, I decided to 'fracture' the forms and spaces, making them more breathable while still holding on to the visually heavy brick volumes of the remains of the monasteries. Additionally, the life and economy of the people of the islands seemed as monastic as is possible outside of a religious monastic life. I looked to reflect that through the materials and treatment of the architecture in general.

The Centre accommodates both a more public working and training side and a more private residential side. How important in the brief was creating a sense of community and a sense of place? Can you engender this through your architecture?

The brief required residential facilities as training is often conducted over a period of a week or more. We also realised that the Centre needed to have enough space to provide areas for interaction or private moments for its residents, obviating the need for them to leave the complex too often for a 'breather'. We also felt there needed to be a sufficient variety and layering of spaces, which would allow for chance and discovery during someone’s stay in the Centre.

There is no air-conditioning: the series of open pavilions and pools you've designed provide natural cooling. How crucial do you feel it is to respond to the requirements of the local climate through material and design rather than through technology?

Situatedness and context is the essence of the value and rationale of my architecture. Nothing, including technology, is outside of this appraisal, but they are governed by context, both human and natural. Human context in turn encompasses all of man's learning and aspirations, from history and philosophy to art and politics.

The building has a very elemental feel in its forms, construction and use of raw brick. Could you comment on this quality in the architecture?

The bare and the essential are at the core of a monastic life but also in the nature of the lives of the people for whom the Centre is built. It serves and brings together some of the poorest of the poor in the country, yet within the extreme limitation of means, there was a search for the luxury of light and shadows, of the economy and generosity of small spaces, and of the joy of movement and discovery.

You can catch Kashef Mahboob Chowdhury talking about the Friendship Centre at the RIBA in London this coming Tuesday 12 February.

This is part of the Architectural Review ar+d Emerging Architecture Lecture Series.