A new project takes unrealized plans for a golfclub’s clubhouse by Mies van der Rohe and makes a 1:1 scale model from the plans. Many questions arise out of this creative gesture: Does it make sense to construct a previously unrealized Mies van der Rohe project as a walk-through model? Can it do justice to him and his design ideas? Or is such a scheme a sacrilege towards the icon Mies? Uli Meyer reports from Krefeld, where they’ve dared to do exactly that.

The backstory: In 2010, a group known as MIK (Mies in Krefeld) was founded under the leadership of art historian Christiane Lange. The society wants to shed new light on Mies van der Rohe’s many years of activity in Krefeld, with Haus Lange and Haus Esters as the best-known examples among a host of built and unbuilt projects. The initial idea was to create a conventional exhibition about the years Mies spent in Krefeld, but then the makers discovered this design for the clubhouse of a local golfclub. Instead of making the exhibition, they decided to build a 1:1 scale model on the project’s original site.

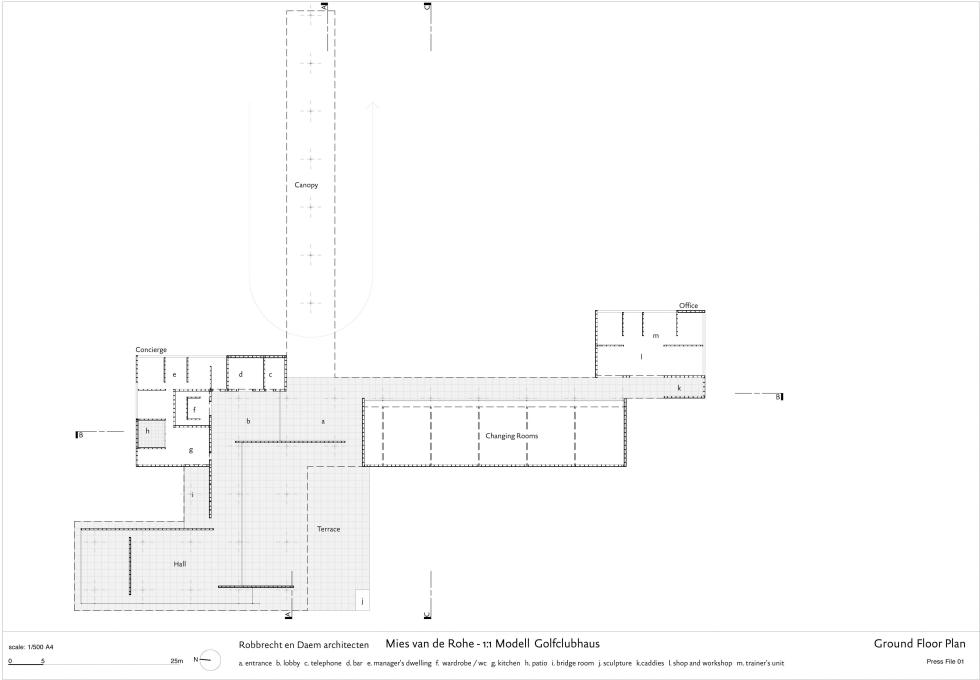

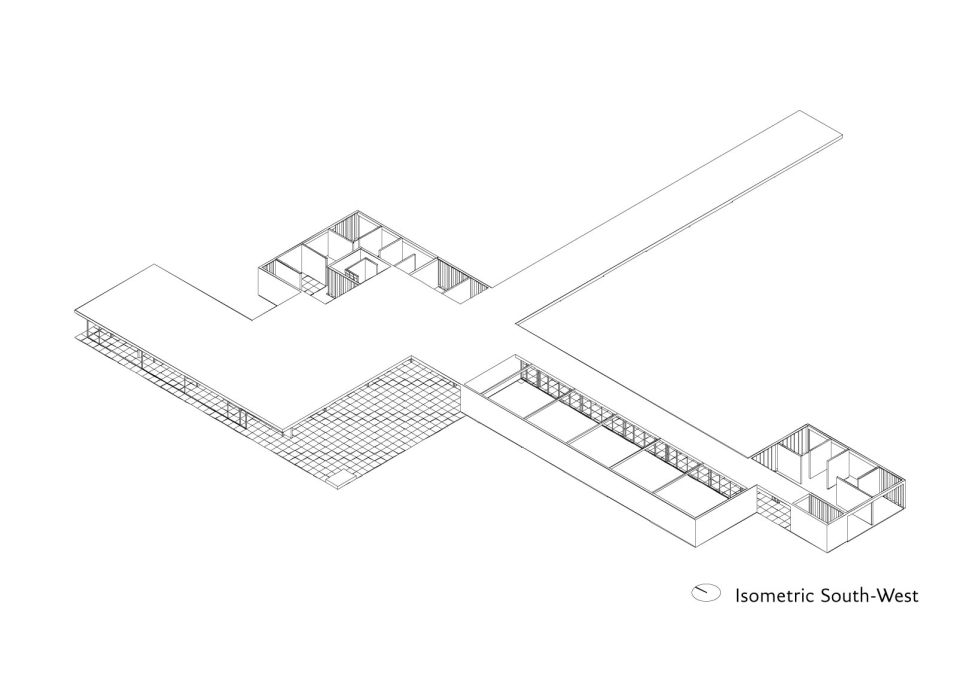

In August 1930, Mies had taken part in a limited competition for the clubhouse. The design, atop a hill on the edge of the former city limits, was conceived as an open, cross-shaped sequence of spaces: in front of the main entrance, a 50 meter long and 7 meter wide roof supported by seven columns reaches out to the east to greet visitors. Combined with the long wing that stretches southward and contains the changing rooms, the grand gesture of the canopy is like an anchor in the landscape. After entering the lobby and then passing along a 20-meter long glass facade, you reach the heart of the building, a 240 squaremeter large hall. This space was to be almost fully glazed – only the east wall would have been solid. Two freestanding walls were to structure the space, and in front of the glass facade to the south, there was to be a covered terrace that would have reached out to an open area and then onward to the golf course. But no winners were ever selected for the competition – the Great Depression made it impossible for the golf club to gather the money needed.

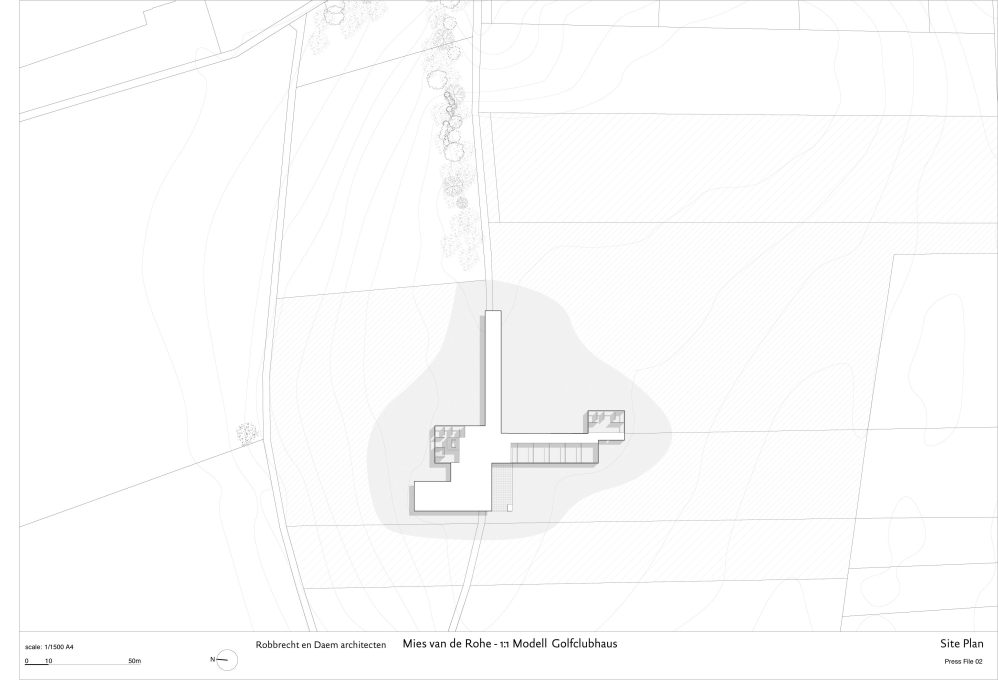

For the MIK society, this design is nonetheless relevant enough to build it as a life-size model eighty years later: “In a certain way, the golf club design enabled Mies to realize his early visions of an architecture that is physically intertwined with nature,” explains Christiane Lange. “The building is anchored to the top of the hill like an asymmetric cross. So for us, it was essential to build the model within the original topography. Luckily, this terrain was never built upon.”

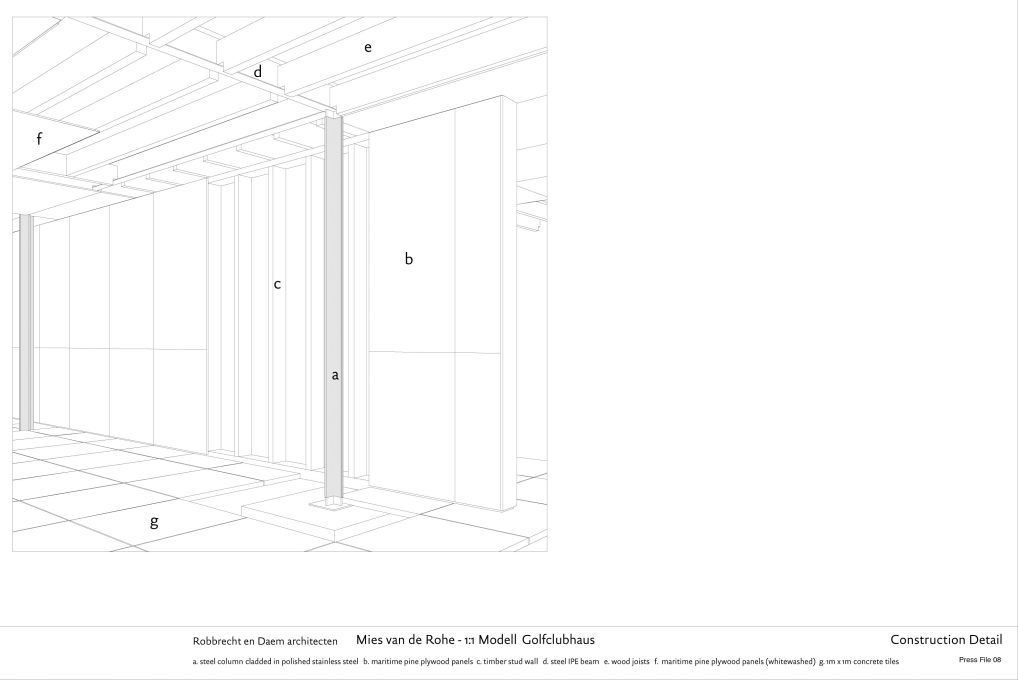

Nevertheless, the model has been built about 300 meters from the original site, which is today a nature reserve. The architects Robbrecht en Daem (Ghent) were commissioned to do the planning. The competition drawings that Mies had designated as “final drafts” served as the basis for their design. A steel-framed structure was built; all the ceilings and non-load-bearing walls are clad with wood and only the steel columns remain visible. Maritime Pine was chosen for the wood panels, which are lightly whitewashed so the wood grain remains visible. The floors are made of square concrete pavers and gravel. Mies had not drawn all the areas in detail, and the architects decided to omit all narrative details. In lieu of speculating about missing information, these areas are simply presented in a sketchy manner: the window frames are recognizable, but have no glass. The floors in the ancillary spaces are gravel and the cladding of the interior walls is missing, as are parts of the exterior walls.

One negative aspect, or at least a drawback, might be that the architects have only faithfully used true Miesian detailing for the distinctive, cruciform-shaped columns. Since the columns are clad with polished stainless steel sheets, their visual appearance comes dangerously close to the chrome-plated columns of the Tugendhat House and the Barcelona Pavilion. The architects describe the columns with their reflective surfaces as “pseudo-spolia” and as the only narrative element in their realized version. But the crude, “real” surface of the underlying steel columns would have been much more in keeping with the materiality of the model.

What has been created is a model that presents Mies’s clubhouse neither as “real” architecture nor as a stage set. What emerges here – perhaps even more strikingly than in a real building – are the central ideas Mies explored with this design: the dissolution of the building in favor of a flowing, open space that is somehow outside but also somehow inside – one that orchestrates the landscape and simultaneously becomes part of the scenery.

To return to the questions posed at the outset: Yes, it’s okay! Constructing the model benefits the Mies enthusiast and the casual visitor. Especially when, thanks to meticulous planning and skillful execution, the result makes visitors realize they are walking through a bit of – in the truest sense of the word – extraordinary architecture. Indeed it is: Mies at its best!

Uli Meyer, Berlin