This is the story of an “unbuilding” project, a Club Med complex eradicated, a landscape reclaimed back to nature. Or is it? asks Julia Schulz-Dornburg. What is this perfected state that we aspire to? Can it actually exist?

This long-since disappeared Club Med, the ruins of which were a favourite destination for architecture lovers, ramblers and explorers, was situated on the rugged coastline of Cabo de Creus in Spain. Built between 1960 and 1962 on boulder-strewn, windswept land, this holiday village was planned to accommodate 1,200 people. The space, meant exclusively for French tourists, was arranged for relaxation, conviviality and exercise. The village-style setup, consisting of groups of two-person living spaces adapted to the rugged topography, drew its inspiration from the architecture of the fishing villages in the area and permitted people to enjoy the climate and the landscape in a direct and natural way, without comforts or luxuries.

The 4.5-hectare complex, closed and empty since July 2004, consisted of 370 single-storey dwellings, two restaurants, a bar, swimming pool, disco, sports court and amphitheatre. Despite being abandoned and run-down, the village retained its appeal. The correspondence between the austere beauty of the rocks eroded by the wind, the scant vegetation and the small white buildings which, dotted among the rocks to form small patios sheltered from the wind, created a suggestive stage set. It wasn't hard to imagine life in the village. “To go off, leave everything, forego your polished shoes and starched collars. To not open a newspaper, to not listen to the radio, to say goodbye to dreary convention, to leave everything and get to be another person for two weeks, far away from the others and close to those who've felt the irresistible desire for a period of gentle exile, for a deep breath... And at last to live what's called life: face to the sun, the sea, the wind, and to laugh, sing, fish and swim.” So Marcel Hansenne, the journalist and 800 metres Olympic swimming bronze medallist, described the club in the 1960s.

After lengthy negotiations with the owners Club Mediterranée, the Spanish government bought the complex in 2005, the aim being to return the land to its original state and to declare it a nature reserve. The 2007 State Administration and the Department of the Environment decided it was necessary to undertake a complete restitution of the natural environment and demolish the village. The public use of the newly restored landscape was to contribute to the knowledge, valorisation and enjoyment of the location. There is no doubt in my mind that the Club Med clients also enjoyed the place – all you need do is glance at some of the old photos of the crowd of youngsters following instructions about diving or dancing in the open air – although the privilege of use was private and exclusively French.

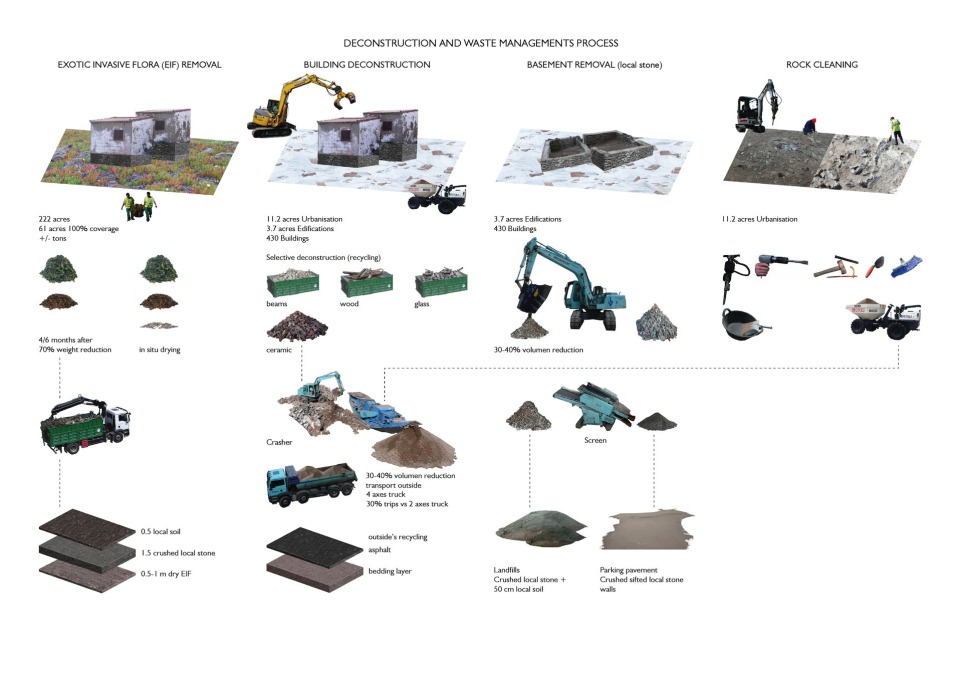

A long and laborious cleaning process seeking to eradicate all traces of people and their activities began in July 2007: the Tudela-Calip Restoration Project. The idea was to return the landscape to its virgin state. Headed by Estudi Marti Franch Landscape Architects (EMF) in collaboration with architecture firm Ardèvol, this was a titanic and very expensive job that lasted until autumn 2011. Altogether, 443 buildings were knocked down, 16,020 cubic meters of road surface was taken out, and 3,419 cubic meters of cove and beach paving were removed – which in turn meant processing 32,720 cubic meters of rubble and 2,941 cubic meters of organic earth contaminated by exotic and invasive plant remains. What an ode to purity! Apparently the plants and mosses in question did not have an immaculate pedigree. The instructions for the deconstruction specified that everything had to be demolished by hand in order to avoid scarring the territory. Structures had to be wrapped in impermeable netting prior to demolition, fixatives had to be applied to the walls in order to minimise the forming of dust which could be deposited in turn in the cavities of the rock when it rained, and the removal of the rubble had to be done by helicopter. The demolition manual was nearly as scrupulous as a surgeon’s operating protocol.

The ambition to restore a landscape, the aspiration towards a perfect topography and the urge for an immaculate nature encompasses the danger of a congealed vision of the territory. The ideal topography, the decontaminated location, the virgin terrain could, after all, turn out to be little more than a scenery without any chance of evolving; a kind of “retired landscape for retired eyes” as Jamie Q. Dern has termed it in his piece “Turismo Cultural” for Quaderns d’Arquitectura i Urbanisme. It is the gaze itself, be it of a retired person, of a Sunday excursionist, of an archaeologist or of an architect, which engenders and composes the landscape. Landscape is a cultural event, not a natural status quo. Nature is continuous, flowing and all-embracing; it has no limit and cannot be divided up. The contemplation of landscape perceives nature as a unitary identity, contrary to the definition of nature as infinite and discontinuous singularity.

When we go in search of the perfect landscape we think we are going out to face nature. When we finally arrive we realise we are the spectators of something artificial. We ourselves are the creators of our landscapes.

– Julia Schulz-Dornburg, Barcelona

Projecte de restauració del paratge de Tudela-Culip (Club Med) al Parc Natural del Cap de Creus from ielei on Vimeo.