What are the first things that spring to mind when someone mentions the red-light district of Amsterdam? Whether you've been to Amsterdam or not, chances are high that cannabis cafés, window whores and dirty little men pop up first on your mental list. Lately, though, things are starting to become a bit less one-dimensional. For several years, the municipality has been trying to add designer studios and art galleries to the red-light blend, and various urban renewal projects are underway in the area, which also happens to be the oldest part of Amsterdam.

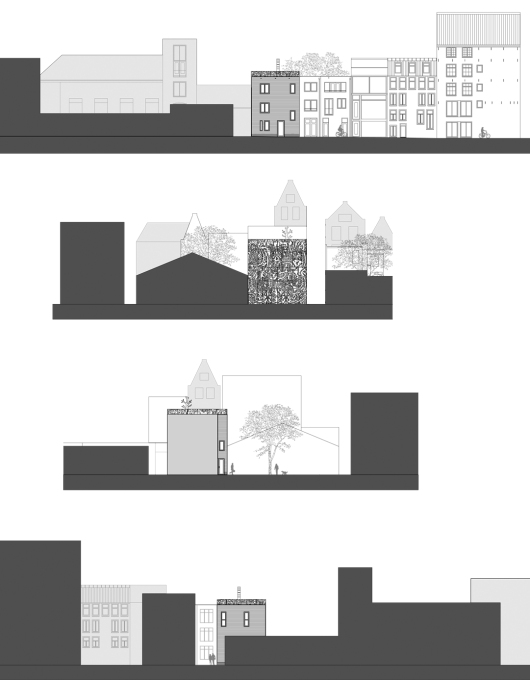

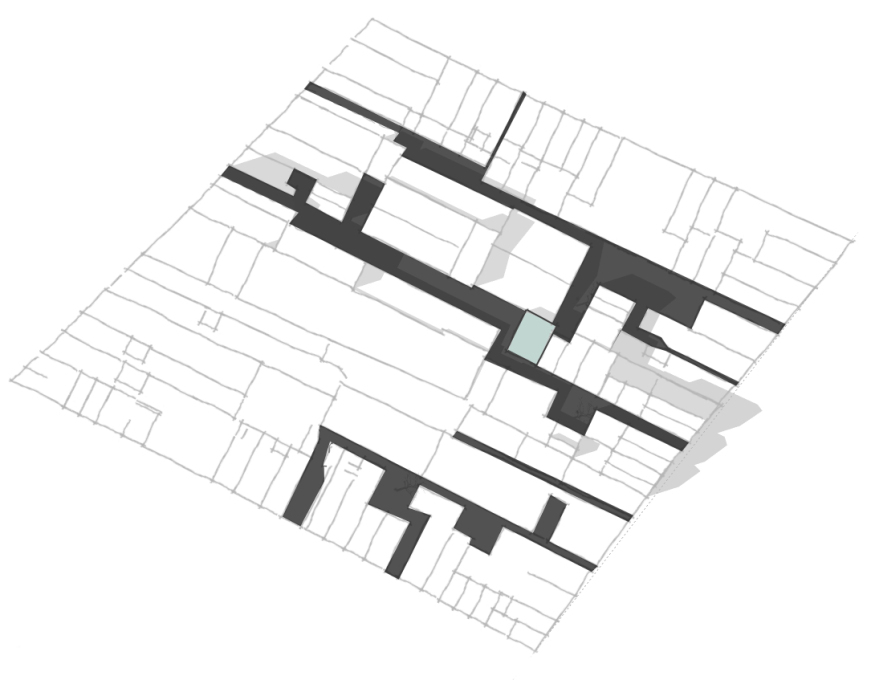

One of these renewal projects is Blaauwlakenblok, a cluster of houses dating back to the 13th century, which was squatted in 1980 and subsequently fell into decay. The housing corporation De Key spent the last twelve years renewing the crumbling old houses, partly replacing them with new buildings, but trying to save as many as possible. What most “stag nighters” and dope tourists don't notice when passing by is that the block, like many others in the area, contains a hidden interior world of narrow alleyways and tiny courtyards, which feels lightyears away from the surrounding seediness. At the end of one of the alleyways, right in the center of this secluded world, sits a newly built house with a perforated white metal façade. Shiny and design-y, the little cube looks like an intruder from a more stylish universe, but somehow also manages to snuggle comfortably into its medieval context.

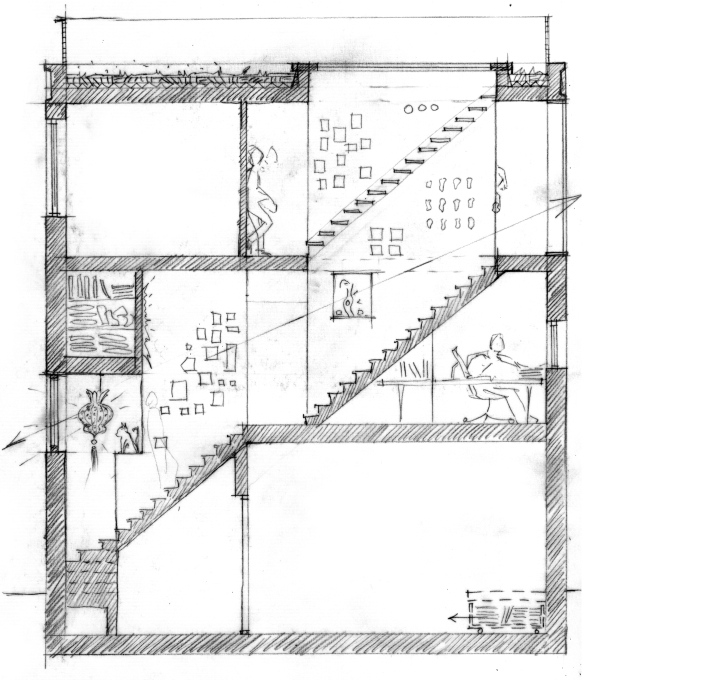

The new building is inhabited by a cartoon artist, who formerly lived next door in an old house that was too ramshackle to be saved. Architect Angie Abbink was called in by the housing corporation to design a new house for him and his family – officially social housing in the form of a single-family social rental house, but in reality a custom-made private home, which fits the family like a glove. The house has three storeys: a studio space for the artist on the ground floor, two bedrooms and a bathroom on the first floor, and a large open kitchen and living room as well as another bedroom on the second floor. Although it offers an impressive 185 square meters of living space, the plastic window frames and low-budget materials used in the interior betray the fact that it had to be built rather cheaply.

The building's claim to architectural fame is its façade, created by Amsterdam-based designer Chris Kabel. As contemporary as it may look, it's also related to the history of the area, where the city's textile industry was located in medieval times. In fact, Abbink selected Chris Kabel for the design because he had worked with textiles and lace before. He created a white façade that wraps the house like a huge lace doily, even forming sliding shutters over the windows and serving as a balustrade for the roof terrace. It consists of powder-coated aluminium plates covered with small punched-out hexagons. By hand-bending the hexagons in one direction or the other, a graphic pattern is generated on the façade. Little marks on the backs of the hexagons told the workers which way to bend them. According to Kabel, the idea came from punching a sheet of paper with a needle from the back and the front, which resulted in a similar texture. It proved to be a simple trick with a huge effect, covering the building with a beautiful metal curtain that constantly changes its appearance, depending on the sunlight. Thanks to this façade, the building stands out, but also fits into its historical context. In fact, even its white colour relates to history: traditionally, all buildings in the alleyways and courtyards of Amsterdam were painted white in order to brighten up these often very narrow and dark spaces.

Officially, the façade is a work of art, which made it eligible for subsidies – and also allowed the architects and the designer to escape from the strict rules of the monument commission. Like the entire Blaauwlakenblok-project, it shows that urban renewal can be a rather non-commercial affair, generating conceptual architecture and not just profitable real estate. The only pity is that the house remains nearly invisible within the urban context. In order to keep out the red-light hustle and drunk tourists in need of a toilet, the formerly public alleyways have been turned into closed-off, semi-private spaces and aren't accessible to non-inhabitants. Only the few passers-by who lift their eyes from the sex shop windows in Warmoesstraat might notice an inconspicuous white sign with a punched-out arrow pointing into the entrance of a building. Behind the doorway, a glimpse of the little white house is just about visible.

– Anneke Bokern, Amsterdam