Tassafaronga Village in Oakland, California is aptly named: its meandering walkways, houses of varying colors and forms, and inviting open spaces generate a surprisingly playful atmosphere in a place once defined by segregation, crime, and economic blight. To put it simplistically, Tassafaronga Village is a housing project. A program that normally conjures up images of bleak and cheap, modernism-gone-wrong constructions. Whether high-rise, like the denounced and destroyed Pruitt Igoe, or low-rise or like the 87 units that comprised Tassafaronga before two years ago, public housing has come to signify monotonous architecture paired with policy failure. Today's Tassafaronga Village is a move forward for the design of public housing in the US. Its success in the community as well as a work of architecture can be credited to its tectonic playfulness, attentiveness to sustainability and affordability, and sensitive spatial consideration for its inhabitants.

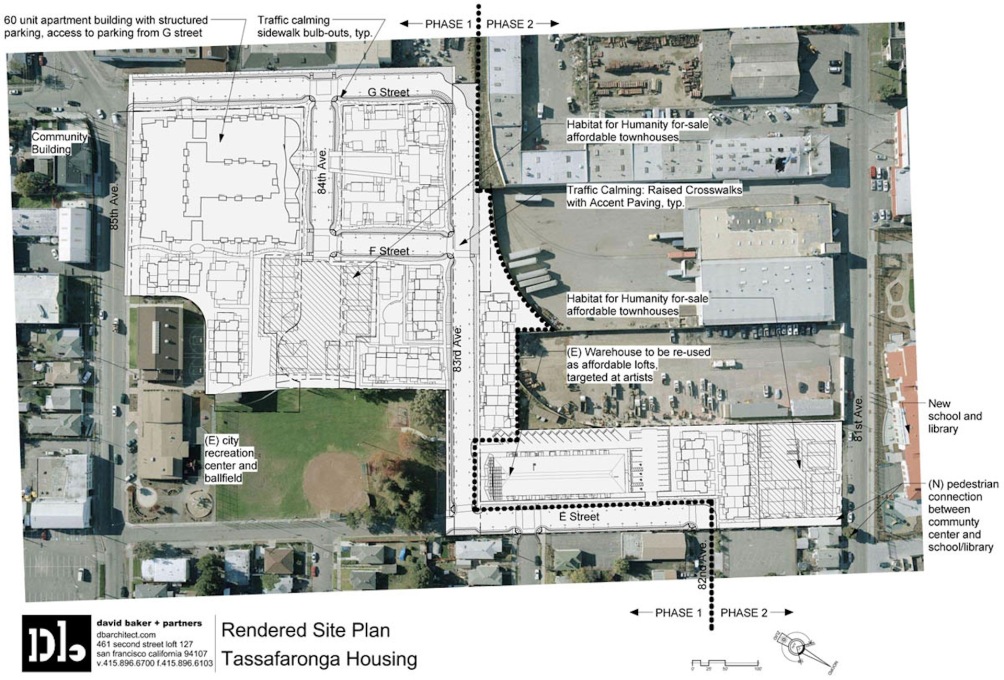

The idea of “bridging” is an evident trajectory in the overall concept of the Tassafaronga project. Designed by David Baker + Partners, a San Francisco-based practice, Tassafaronga is an exercise in connecting extremes in urban typologies and shifting demographics. The architects populated the site with a set of buildings that are widely varied in material, color, and formal palettes. Whether wandering around a block of townhouses, turning the corner of the three-story apartment building, or walking along the residential loft complex, it's increasingly clear that no two structures look the same. Here, individuality has supplanted public housing's historically homogenous design strategies: the undulating facade of the apartment building stands in strong contrast to the colorfully cubist dynamism of extending residential balconies, receding entryways, and upturned solar panels; verdant and local greenery grows alongside warm red paint on stucco and charcoal-gray wood siding; and ivy covers a brightly painted boundary wall piqued with gnarly and aggravated barbed wire. And what is left open is just as sensitively designed as what is built. Instead of the traditionally isolated, almost militarized positioning of urban housing projects, Tassafaronga enables a variety of open and green spaces for the Village residents and community members alike.

As the result of DB+P's incorporation of the site's history, Tassafaronga showcases a collage-like architectural language. The residential loft building, dubbed the “Pasta Factory,” is a re-imagining of the abandoned pasta factory located on the site that had fallen into disuse. The dark wooden balconies that are a recurring theme in most of Tassafaronga's residential constructions are interwoven with the Pasta Factory's original façade, where its old signage and the new design elements create a multilayered mashup. Not only are space and time sampled and recomposed, but building use as well: the ground floor of the Pasta Factory houses a public medical clinic directly beneath the repurposed residential lofts.

Tassafaronga can be seen at the boundary between two polarized cities: The Bay Area is where a growing homeless population lives in the shadow of one of the country's highest per-capita earners; where news outlets are saturated with features of Silicon Valley's latest technology release or San Francisco's newest startup while little coverage is given to the suffering industrial and service spaces that buttress such innovation. Too often are these two adjacent cities seen as immutability separate and incongruent.

The village engages a site on the interstice of the industrial, residential, and environmental (the Tassafaronga development has achieved one of the first LEED ND Certified Gold plans, and all of the Tassafaronga buildings are certified LEED for Homes Platinum). Using the “village” as a design principle, DB+P introduces an element of urban density that the peripheral industrial communities often lack. East Oakland, Tassafaronga's surrounding neighborhood, is comprised of vast garages and impound lots, emptiness beneath highways and rapid transit rails, and either the low-rise housing projects or single-family houses that define much of living in East Oakland. Drugs, prostitution, and the consequential crime has proliferated in the last thirty years, but since Tassafaronga opened in 2010, the crime rate has dropped 25 percent compared to the old housing project's rate in 2007.

It would be optimistic to say that architecture can reverse a generation of urban ills (one can't help but notice the excessive installation of security cameras throughout Tassafaronga), but these numbers are hopeful. Besides creating a visually different housing development comprised of affordable units, there's an effort to foster a sense of individual and collective ownership here: twenty-two of the townhouses were built in partnership with Habitat for Humanity for families that were able to buy the homes by putting in hours of sweat equity to aid in their construction. And most importantly, the feeling in this community is different. A recent Sunday afternoon showed Tassafaronga at its most picturesque: communal barbecues, children playing tag in the square, a pair of neighboring families tending the community garden and gathering ripe vegetables into baskets. But the most exciting thing the potential for people to come in from surrounding areas, whether to call on a friend, sit in the garden, or visit the clinic. That openness alone is the most valuable bridge Tassafaronga has built.

-- Elizabeth Feder, San Francisco