-

(Photo courtesy Columbus Area Visitors Center)

-

Until this year I had no idea that the so-called “sixth most important city for architecture in America” was just an hour’s drive away from my Indiana hometown. But on a long-overdue visit to Columbus, Indiana last summer, I encountered a veritable mecca for architecture devotees. Nestled within its city limits over 80 pieces of notable architecture can be found — many of them modernist masterworks by the likes of Eero Saarinen and I.M. Pei.

As much as the buildings themselves, it’s the story behind the architecture that makes Columbus so compelling a place. This is a story that reaches across generations, illuminating the ways in which the history of modern architecture in America is intertwined with the histories of industrial development, private enterprise, and public service. It’s a story firmly rooted in Midwestern culture, but it’s as much a story about Indiana as it is about the country as a whole − getting right to the heart of one fundamental question: what is the value of investing in public architecture?

Columbus’s wealth of architecture includes six national landmarks and work by four Pritzker Prize winners: Kevin Roche, I.M. Pei, Richard Meier, Robert Venturi. (Photo courtesy Columbus Area Visitors Center)

-

Cummins Engine Company

The architectural marvel that is Columbus is the result of innovative and unique political, entrepreneurial, philanthropic, and civic experimentation on a city-wide scale. The man behind the experiment was J. Irwin Miller, and Columbus was his petri dish.

Miller was born in Columbus in 1910. After studying at Yale and Oxford he returned home in his twenties to take over management of his great uncle’s business, the Cummins Engine Company. In the 1930s at the height of the Great Depression, Cummins was an ailing enterprise – yet under Miller’s savvy management as the national economy began to recover, the company finally began to profit.

Cummins expanded throughout World War Two thanks to the war industry’s demand for diesel engines, and it continued to grow as the construction of the nation’s first interstate highway system stimulated a postwar manufacturing boom. Today, Columbus is still an industrial hub — a vital 37 percent of employment is in the manufacturing sector, much of it automotive, and much of it powered by the company now called Cummins Incorporated. Miller was undoubtedly the business genius behind the success of the company that has defined the city for the last century — and in turn he became a defining figure.

J.Irwin Miller inspecting a diesel engine at Cummins circa 1950. (Photo © 2012 Indiana Historical Society)

-

From a letter by Elsie Sweeney, Miller’s aunt, that tells the story of how their family convinced both the community and the architect to build a modernist church.

THE ECUMENICAL MODERNIST

Fueled by its thriving industry, Columbus almost doubled in size between 1920 and 1950, ballooning to a population of around 18,000. The baby boom demanded new public infrastructure, and fast — schools and churches were quickly becoming overcrowded.

Miller was an avid Christian. In his twenties, he also became an avid devotee of modern architecture. When the congregation of his family church outgrew its cramped building in the early 1930s, he seized on the opportunity to join his passions and hire a practicing modern architect to come to Columbus to design a new church.

Miller believed in the importance of contemporary architecture at a time when traditional styles, particularly for religious buildings, still reigned in the USA. Convincing the church congregation to build a modernist church wasn’t easy — but persuading the architect turned out to be just as hard. Miller’s top choice was Finnish architect Eliel Saarinen, who was based in nearby Detroit. Unfortunately Saarinen was no fan of American religiosity, and he was explicitly against the idea of building an American church. “They are too theatrical – they are not my idea of religion,” he reportedly told Miller’s mother.

Miller’s entire extended family became enthusiastic proponents of the plan, and over time the Miller-Irwin-Sweeneys managed to persuade Saarinen. They argued that modernist architecture was needed precisely because it reflected their specific religious values. Informed by the Ecumenical movement, which promotes interdenominational unity, theirs was a particularly Midwestern brand of religiosity: moderate, modest, and inclusive. Miller’s mother explained: “While we should like the church to be beautiful, we do not want the first reaction to be, how much did it cost?”

-

First Christian Church was built by Eliel Saarinen in 1942 and was the first modern building in Columbus. It has a simple, geometric form, with a buff brick and limestone façade and a 166-foot high free-standing belltower. (Photo courtesy opus408d.blogspot.de)

-

Southside Elementary School, built by Eliot Noyes in 1969, is a stunning Brutalist structure of precast concrete. Despite its stature, parents have been known to question its appropriateness – isn’t elementary school brutal enough?

The Cummins Foundation

In the 1950s, the Bartholomew County Public School Board of Columbus realized a new elementary school would have to be built every two years to keep up with increasing citywide birth rates. Two pre-fabricated school buildings were hastily erected. Upon observing the shoddy quality of the structures, Miller decided to stage another architectural intervention.

In 1954 he founded the Cummins Foundation for public architecture, financed by profits from his thriving corporation. He approached the school board with a proposal: he would draw up a list of five possible architects to build the next school, and if the board could agree on one, the foundation would pay the architect’s fees and ten percent of the construction costs. Harry Weese was invited to take on the first project, designing the Lillian C. Schmitt Elementary School in 1957.

Miller’s proposal met with resounding success, and under its aegis four schools were built in five years. He soon decided to expand the program’s reach, and over the coming half century it would facilitate the construction of everything from fire stations and hospitals to golf courses and public housing. In each situation, the choice of architect was left to the governing body of the institution. They ended up selecting many of the architects who would come to shape modernist architecture in the USA, partially through their work in Columbus.

The participative aspect of this process was a crucial facet of Miller’s philosophy. He wanted local organizations to have a say in developing the landscape of their city, and he wanted the architects to be welcomed rather than met with skepticism. This allowed for experimentation that might not have been able to take place elsewhere; with community support, unique projects were made possible.

-

Robert Venturi completed Fire Station No. 4 in 1967, fulfilling the fire department’s request for a fully-functioning station on a tiny 200 by 125-foot site via a trapezoidal floorplan with few interior right angles. (Photo: courtesy Columbus Area Visitors Center)

Irwin Office building, formerly the Irwin Union Bank, was a collaboration between Eero Saarinen and landscape architect Dan Kiley in 1954. It was one of the first banks in the USA to abandon neoclassical style in favor of open space and glass. (Photo: courtesy Columbus Area Visitors Center)

Lillian C. Schmitt Elementary School was built in 1957 as Cummins Foundation’s first project. (Photo: Harry Ueese)

-

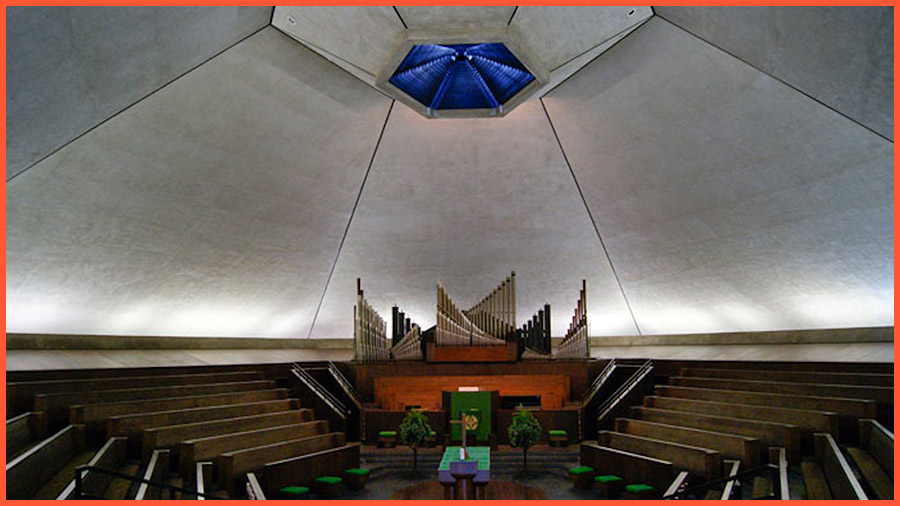

Cummins did not finance churches or private businesses, but as Columbus gained an identity as an architecture destination, local citizens began to invest their personal resources in high-quality architecture. Eero Saarinen’s North Christian Church, completed in 1964, was one such building financed by private means. (Photo: courtesy Columbus Area Visitors Center)

-

Miller House & Garden

When Eliel Saarinen arrived in Columbus in the 1940s to break ground for First Christian Church, he brought along his son Eero and Eero’s friend Charles Eames. Miller became fast friends with Eames and the younger Saarinen and thus began a lifelong friendship and working relationship.

In 1953, Miller bought a 13.5-acre plot of land on the northwestern edge of Columbus and asked Eero Saarinen to design his family’s home there. Over the next four years Saarinen, along with interior designer Alexander Girard and landscape architect Daniel Kiley, worked to create what would become one of a handful of iconic glass houses signaling the advent of modernism in America, alongside Philip Johnson’s Glass House (1949), Charles and Ray Eames’ Pacific Palisades House (1949), Mies van der Rohe’s Farnsworth House (1951), and Eliot Noyes’ house in New Canaan (1954).

With its low-slung roof, walls of stone and glass, and cruciform steel columns, the Miller House epitomizes the modernist dwelling of its time. (Photo: Leslie Williamson, courtesy Dwell)

-

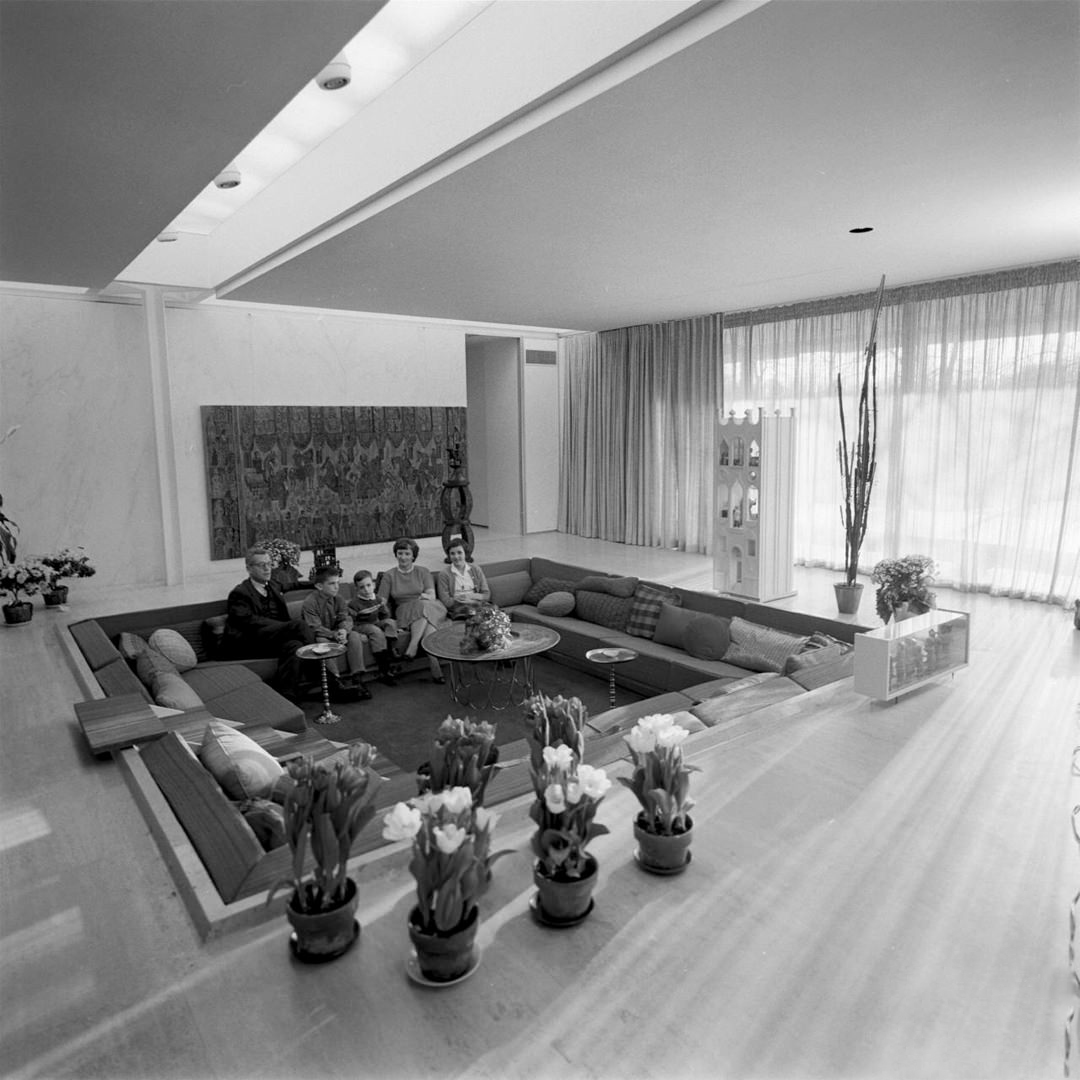

The Miller family were photographed in their home for LIFE magazine in 1961. Today the home is preserved as a museum and open to the public. (Photo: Frank Scherschel)

As opposed to most of its contemporary glass-walled houses, the Miller House was made to be lived in. Saarinen’s “Conversation Pit” was one of several features designed for the seven-person Miller family. (Photo courtesy IndyStar)

-

“This man ought to be president”

Miller intended for his architecture initiative to attract people to Columbus. This hope was partially driven by a personal desire to have interesting people around him — he wanted to engage in conversation with the thinkers of his day. But it was also in his personal financial interest to make the city appealing for new citizens. As Columbus became known for its rich local culture, it became more attractive for job seekers; in other words, as quality of life went up in Columbus, so did Cummins’ employee pool. Furthermore, his investment fed back into the long--term city economy via tourism, which today accounts for over USD 300 million of annual revenue.

Herein lay the crux of Miller’s experiment. With the Columbus model Miller demonstrated how investing in culture can feed back into private business, creating a symbiotic relationship between social and economic growth. He practiced philanthropy with a business incentive, proving that fostering public well-being can directly contribute to private gain. As a partisan debate about whether it is more profitable to invest in business or culture continues to divide the country today, Columbus remains relevant and powerful evidence that the two can be mutually supportive.

Besides his contributions to public life through architecture, Miller also used his business success as leverage for civil rights causes. On the local scale, he unionized the labor force at his own factories; on the national scale, he helped organize the civil rights March on Washington; globally, he declined to invest in South Africa as a protest against Apartheid. In 1967, Miller's profile graced the cover of Esquire with this superlative subtitle. (Image © Indiana Historical Society)

-

Impressively unspectacular

As I walked the streets of downtown Columbus on a weekday afternoon last summer, a tourist map in one hand and a camera in the other, I scrutinized the city for signs of that special aura that our current era of starchitecture has taught us to expect. There were plenty of formally-impressive structures to be found — the cuboid volume and colossal tower of First Christian Church; the dramatic brick arms of City Hall; the massive dome crowning the Bartholomew County Jail — but overall I was struck by the pleasant ordinariness of it all.

Kids were leaving summer sports practice from Gunnar Birkerts’ stunning monolithic school. The sunlit brick interior of the I.M. Pei library was bustling with teenagers gossiping over their books.

(top) Students at Lincoln Signature Academy play sports, eat lunch, and attend lectures every day in this multi-purpose space designed by Gunnar Birkerts in 1967. (Photo courtesy Columbus Area Visitors Center)

(right) Cleo Rogers Memorial Library was built in 1969 by I.M. Pei, who was chosen over contenders Phillip Johnson and Irving Stone for his plan based on the form of a public plaza. (Photo: Elvia Wilk)

-

It’s not that fantastic architecture is taken for granted in Columbus. It’s that, over decades, the architecture initiated by Miller has been fully integrated into the fabric of everyday life. The buildings may serve a secondary function as archi-tourist attractions, but unlike much pilgrimage-worthy architecture, they serve primarily as inhabited, functional public spaces. Miller’s greatest achievement was not to persuade the giants of modernism to descend on a sleepy midwestern town. It was to make well-designed architecture ubiquitous and accessible enough to seem entirely warranted in a normal place. It was, overall, to make great architecture seem entirely....ordinary. I

The steeple of Birkert’s St. Peter’s Lutheran Church (1988) rises up over football goal posts and street signs in the heart of the city. The cityscape of Columbus is perpetually evolving, still due in large part to the Cummins Foundation, which continues to support an average of one new piece of architecture a year since 2000. (Photo: Elvia Wilk)

-

Search

-

FIND PRODUCTS

PRODUCT GROUP

- Building Materials

- Building Panels

- Building technology

- Façade

- Fittings

- Heating, Cooling, Ventilation

- Interior

- Roof

- Sanitary facilities

MANUFACTURER

- 3A Composites

- Alape

- Armstrong

- Caparol

- Eternit

- FSB

- Gira

- Hagemeister

- JUNG

- Kaldewei

- Lamberts

- Leicht

- Solarlux

- Steininger Designers

- Stiebel Eltron

- Velux

- Warema

- Wilkhahn

-

Follow Us

Tumblr

New and existing Tumblr users can connect with uncube and share our visual diary.

»Architecture starts when you carefully put two bricks together. There it begins.«

Ludwig Mies van der Rohe

Keyboard Shortcuts

- Supermenu

- Skip Articles

- Turn Pages

- Contents