-

Le

Village

RadieuxLe Corbusier’s big city visions funnelled into a small town

Text by Anneke Bokern

-

A mountain of modernism: the concrete cone of the church of Saint-Pierre provides a back-drop to a Firminy street, one that is almost on the scale of the nearby hills. (Photo: Allard van der Hoek)

The square in front of the little train station of Firminy is incredibly neat. Coming from the nearby industrial moloch of St Etienne, you feel like you’ve landed on a different planet. The gravel is freshly raked, the lawn almost artificially green. A shopping street leads into an unremarkable town centre, with a market square, city hall, neo-gothic church and some typical French corner bars. Nothing could be more ordinary. Until you turn up a small street lined by old workers’ houses and suddenly a huge concrete cone looms at its end. Silent and monolithic, it sits like a fossilized spaceship. Yet despite its archaic appearance, it’s the one of the youngest buildings in town.

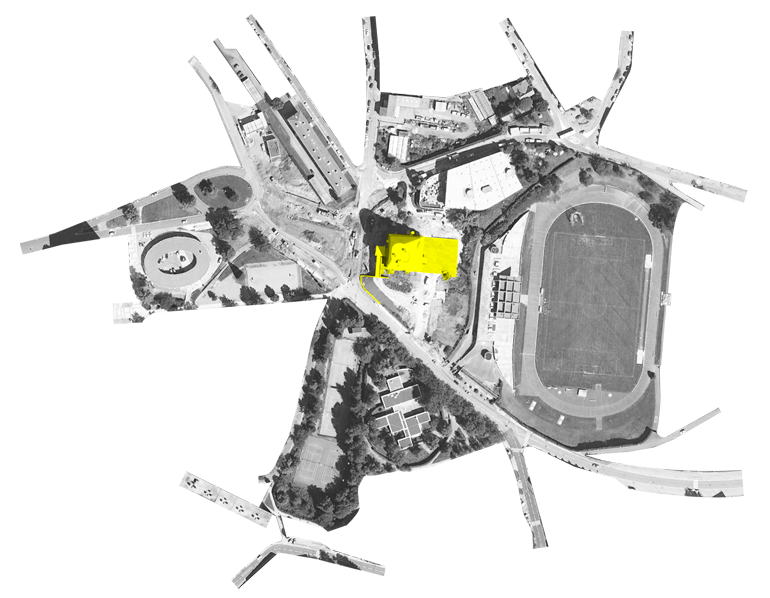

The concrete cone is the church of Saint-Pierre, designed by Le Corbusier around 1961, but finished posthumously in 2006. It’s actually the fourth building by the architect in Firminy, giving this one-horse town in central France, with its 17,000 inhabitants, the highest per-capita concentration of Corbu-buildings in Europe. In fact, you’d have to travel as far as Chandigarh to find more of his works in one place. As well as the church, there’s a Corbu Unité d’Habitation, stadium and cultural centre. The huge Unité is enthroned on a hill behind the town, but the other buildings look as though they have rolled together into the hollow below like marbles. Together with a swimming pool and a gymnasium, designed by Corbu’s student André Wogenscky, they were all planned as the social centre of Firminy Vert, the modernist city extension, awarded the Grand Prix d’urbanisme in 1961.

»Silent and monolithic, it sits like a fossilized spaceship«

-

»We have to build the city in the sun, in the light, surrounded by nature, that’s what determines our urbanism«

City in the Sun

Firminy Vert was first proposed by Firminy’s then mayor Eugène Claudius-Petit, formerly the French minister for reconstruction and urbanism. At that time Firminy must have been a pretty grim place. A dirty, black mining town, stuck knee-deep in the 19th century. The population, which had expanded from 2,600 inhabitants in 1820 to over 20,000 in 1937, was still living in conditions similar to the early days of the industrial revolution, whilst coal mining and iron smelting remained its main industries.

So Claudius-Petit decided to build a new worker’s housing area, naming it Firminy Vert – “green Firminy”, as opposed to the existing sooty “Firminy la Noire” or “Firminy the black”.“We have to build the city in the sun... in the light... surrounded by nature”, he proclaimed, “that’s what determines our urbanism. We have to build it with dignity, that’s what determines our architecture. We have to build it with simplicity, because we’re poor.”

If Claudius-Petit had had his way, Firminy would have become even more of a Corbu “Valhalla”. At the start he wanted his architect friend to design Firminy-Vert’s masterplan as well as its buildings. But after the inhabitants of Firminy heard stories about Le Corbusier’s megalomanic plans for a ville radieuse, he was only asked to design the centre civique, while a no-name colleague was given the commission for the urban plan. Nevertheless, it remains very Corbusian: 4-storey apartment blocks floating in green space, interspersed with high-rise slabs and tower blocks; its architecture is modernist in a rational, serialised and unobtrusive way.

-

Central “Firminy Vert,” originally slated to be completely planned by Le Corbusier, showing the numerous modernist high-rise residential towers around the Church of Saint Pierre. (Photo: Allard van der Hoek)

-

Later, in 1965, Le Corbusier was also commissioned to design three Unités for Firminy Vert, but only one was realized. It has suffered a mixed fate: a modernist latecomer, it wasn’t popular and a third of it was closed up in the late seventies, due to a lack of tenants for the apartments. Twenty years later, however, the entire building was reopened - with the exception of the top floor school, which remains a sealed time capsule.

One Unité d’Habitation was completed in Firminy (three were planned). This housing block contains around 500 apartments and originally had a school at the top for the residents’ children. Since its closure, its mothballed interiors are still full of the original furniture and features, like low-level windows in the school designed for the young pupils. (Photo: Allard van der Hoek)

-

The church of Saint Pierre is otherworldly inside and out, whether in the day or at dusk. These photographs show the building just after completion in 2006. (Photo: Allard van der Hoek)

Abandoned science-fiction movie set

Entering the centre civique is like walking onto the set of a science fiction movie. The hovering concrete volume of the cultural centre, the flying roof of the stadium, the insectlike gymnasium, and the church stand out. Finished by Le Corbusier’s former student José Oubrerie, Saint Pierre is an anachronism: simultaneously new, ageless and dated. It has a breathtakingly beautiful interior, due to Le Corbusier’s extraordinary arrangement of windows and use of coloured glass. The space has a sacred but not specifically Christian feel. Barring the pews and altar, this could be the pagan temple of an extraterrestrial civilization.

Unsurprising perhaps: Le Corbusier was not a particularly fervent Christian himself and only agreed to design the church because it was “for workers and their families.” The bishop of Saint-Étienne disliked his design however, and withdrew the commission. After the architect’s death, construction was started anyway, financed by a private foundation, but they had only progressed as far as the plinth when the contractor went broke. The stump of the church, listed as a monument in 1995, was finally finished in 2006 – for rather profane reasons: Firminy hoped to attract more tourists and EU subsidies by completing the Corbu-ensemble, its only local sightseeing attraction. The church has never seen a single service, acting purely as a cultural venue.

-

The interior of the Catholic church of Saint-Pierre de Firminy, with pinpoints of light coming through the small round window apertures, designed by Le Corbusier to represent the constellation of stars in Orion. (Photo: Allard van der Hoek)

»this could be the pagan temple of an extra terrestrial civilization«

-

Fragments of a “Brave New World” (from left to right): Le Corbusier’s Youth and Cultural Center, a local school, and the roof terrace of the Unité d’Habitation, also by Le Corbusier, with the concrete sandpit of the former school’s playground. (Photo: Allard van der Hoek)

-

The dome-like form of the church of Saint-Pierre and the stadium with its flying roof , both designed by Le Corbusier, are two of the monumental buildings that form the civic centre of Firminy Vert, set against the surrounding countryside. (Photo: Allard van der Hoek)

-

Anneke Bokern is an architecture, design and art journalist, based in the Netherlands where she has been living since 2000. She writes regularly for German and international publications such as Bauwelt, Baumeister, DAMn°, MARK, Azure, Die Welt, Neue Zürcher Zeitung. With her company architour, she organizes architectural guided tours in the Netherlands. She has also contributed to various books and is the author of a Marco Polo guide to Amsterdam.

In Firminy, as in any village or small town in France, men gather to play boules. Less typical is the mammoth modernist public housing block looming behind. (Photo: Allard van der Hoek)

Le village radieux

Today Firminy Vert still isn’t a wealthy place statistically. Of the town’s 1,800 apartments, 1,400 are council-owned. More than 60 percent of the welfare recipients of Firminy live there, and nearly 30 percent of its adult inhabitants don’t have a high-school diploma. Unexpectedly, however, Firminy Vert is just as surreally tidy as the railway station’s square. The buildings are freshly renovated, there’s no litter on the grass, no tagging on the walls, no urine-stench in the corners. Women push prams under chestnut trees. Men play boule in front of the giant housing slabs. Families’ laundry hangs drying in a communal square behind brise soleil. This place actually seems to work.

So is this the modernist dream come true? Or is there a hitch? It all looks so perfect one suspects something must be wrong; a dark secret hidden under the perfect turf. The reason however may be simpler. Firminy-Vert isn’t a satellite of a big city, but an extension of a small town where everything is within walking distance. Maybe the modernists’ city planning ideas were better suited for towns the size of Firminy than Paris or Moscow. Le village radieux? I doubt Le Corbusier would have liked this conclusion. p

-

Search

-

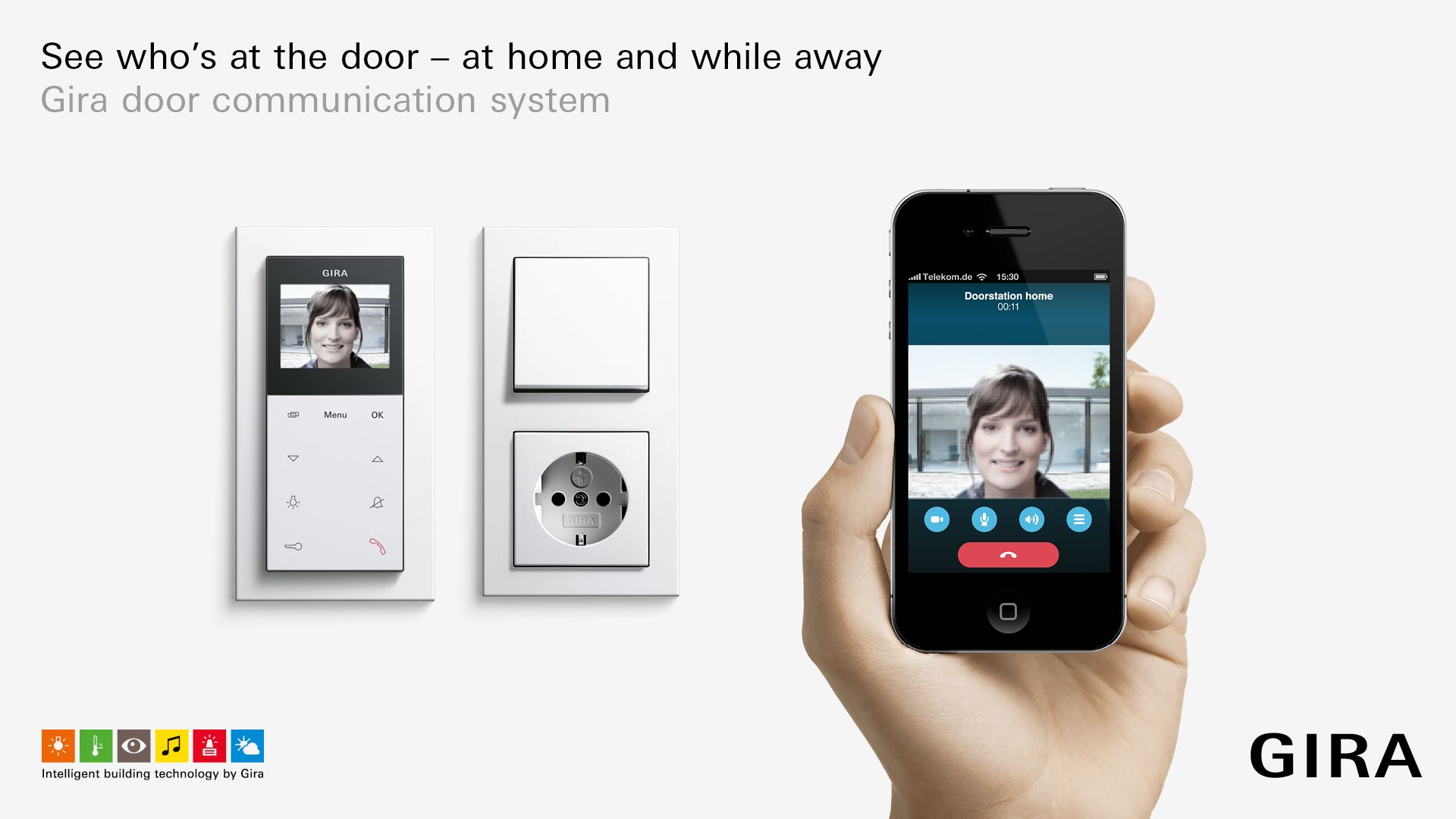

FIND PRODUCTS

PRODUCT GROUP

- Building Materials

- Building Panels

- Building technology

- Façade

- Fittings

- Heating, Cooling, Ventilation

- Interior

- Roof

- Sanitary facilities

MANUFACTURER

- 3A Composites

- Alape

- Armstrong

- Caparol

- Eternit

- FSB

- Gira

- Hagemeister

- JUNG

- Kaldewei

- Lamberts

- Leicht

- Solarlux

- Steininger Designers

- Stiebel Eltron

- Velux

- Warema

- Wilkhahn

-

Follow Us

Tumblr

New and existing Tumblr users can connect with uncube and share our visual diary.

»I don’t mistrust reality of which I hardly know anything. I just mistrust the picture of it that our senses deliver.«

Gerhard Richter

Keyboard Shortcuts

- Supermenu

- Skip Articles

- Turn Pages

- Contents