-

THE LIGHTEST TOUCH

Architect Greg Lynn believes the good outweighs the bad when it comes to carbon composites

Interview by Sophie Lovell

-

Famous in the 1990s for his ‘blob architecture’, the architect and designer Greg Lynn, is now working a lot with carbon composites, with his FORM studio team in Venice, California, continuing his investigations into the integration of structure and form. He talked to uncube about the potential and pitfalls of working with the material and how design thinking needs to shift to incorporate its properties.

When did you first start working with carbon? What were your reasons for using it as a construction material?

I started using composites because I was looking for a translucent rather than transparent material, similar to when I used glass fibre years ago. The principles are the same: it’s what I call ‘rigidized cloth’ – fabric and woven goods stiffened with resins. The difference between carbon and glass fibre is in the stiffness than weight or strength: they’re almost identical – especially for architectural applications – but if you want to eliminate deflection and make something really stiff you use carbon. But carbon’s black fibre aesthetic is really different and has current associations with high performance sports and luxury.

I remember a series of Prada magazine advertisements, which used 3DL™ load path carbon and aramid North Sails as a backdrop: the curved lines of carbon twill looked like the hatching on a Piranesi drawing. And I know of architects who’ve worked it into buildings, like Renzo Piano at his Americas Cup building in Valencia: he draped the Team Prada headquarters in used sails.

-

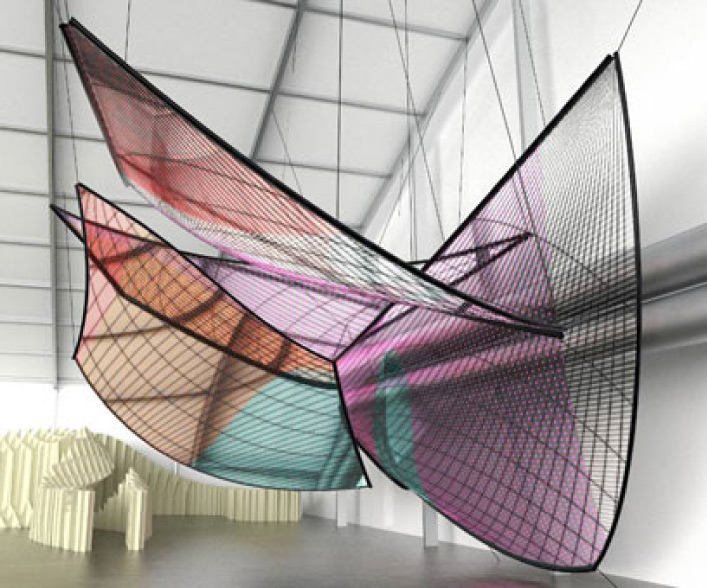

Carbon Crystal Sails: carbon and dyneema North Sails with millions of crystals sandwiched into a translucent membrane. Greg Lynn for Swarovski Crystal Palace, Design Miami, 2009. (Photo courtesy Swarovski Crystal Palace)

Renzo Piano Building Workshop’s façade system made from 3DL™ load path carbon and aramid North Sails for Prada SpA’s Luna Rossa Teambase, Valencia, Spain, 2005-6. (Photos: Enrico Cano)

-

The first time I worked with carbon was for Swarovski’s Crystal Palace exhibit at Design Miami 2009. I designed hanging surfaces of carbon and dyneema made by North Sails with millions of crystals sandwiched into its gossamer translucent membrane.

At the end of the 90s some of the Droog designers did work with carbon fibre, notably Hella Jongerius with her Kasese Chair, Marcel Wanders with his Knotted Chair, and later Bertjan Pot.

Carbon fibre 1⁄5th scale RV (room vehicle) Prototype House at the Hercules Campus in Playa Vista, California. (Photos courtesy Greg Lynn FORM)

But they seemed to drop it again quite quickly. Pot told me that as a material “it has issues” and is very expensive…

Actually, it keeps getting cheaper. The real problem for the use of carbon in industrial products, or any composite for that matter, is cycle time. I designed what has to be the lightest hanging chair ever made as a prototype for the Art Institute of Chicago in soft flexible carbon pre-preg tapes manufactured by North Sails.

-

They were placed and laminated manually from four-inch wide tapes and they take two people at least an hour, because you are really placing material at the fibre level in multiple orientations based on load paths. It is similar to tailoring in terms of time and labour. Because of the time it takes to laminate, cook and cure carbon objects it becomes prohibitive for the world of high volume production in furniture and automobiles. For Formula One cars, for example, there is not a piece of metal left on the structure and body of the car any more – only in the engine – and even most of that metal is being replaced by handmade, labour-intensive carbon. A lot of people think these things are made by machines, but really it’s one of the last truly artisanal craft-based methods of construction. It will get more industrialised, but it hasn’t yet.

Isn’t the very nature of carbon composites environmentally problematic, in terms of recycling or breaking down the materials afterwards?

»Building with carbon fibre is one of the last truly artisanal craft-based methods of construction.«

Not really. Michael Lepech at Stanford published his comparison of composites with other construction materials and, more often than not, because of their light weight and high strength, they often use less material and out-perform materials like wood, masonry and steel that take more energy to manufacture, transport, assemble and support. In Lepech’s comparisons, if you include the stuff they put in wood to keep it from rotting and to discourage insects from eating it and so on, a wood-framed building ends up being more toxic with a larger carbon footprint than an actual carbon fibre building. Yes, it is environmentally nasty to burn piles of sand into fibre using huge amounts of energy and then glue the sand together using petroleum resins around foam cores. But when you look at how little material is used, how much steel is saved in holding up these lighter materials, how much energy is saved in transport, longevity and performance, it is easy to see why composites are high-performance.

-

It sounds like we are still at the very beginning of using carbon composites in manufacturing, structures and objects. Because of these manufacturing difficulties do you think carbon will turn out retrospectively to be just some kind of interim material?

In the US, the transportation infrastructure is dangerously antiquated and badly maintained. Much of the current reinforcing and retrofitting of bridges and overpasses is glued carbon strapping. For certain niche building industries, like bridge-building, retrofitting infrastructure and mining, carbon is already a mature material. It’s been around for 60 years or so. The capacity in China now far exceeds the demand – that’s because manufacturers such as airlines are eliminating aluminium and changing to composites. No one would consider designing a new commercial airplane in metal anymore – we have to go to carbon because it is so much more energy efficient. I think the issue with a delayed adoption of the material in buildings and commercial products is that designers frankly don’t understand the principles of it. Until designers understand at a conceptual level how to use carbon composites, they won’t use it appropriately and therefore it won’t be a sensible alternative.

Each component of the main hull of Greg Lynn's carbon composite GF 42 trimaran is made painstakingly by hand. (Photos courtesy Greg Lynn FORM)

Each component of the main hull of Greg Lynn's carbon composite GF 42 trimaran is made painstakingly by hand. (Photos courtesy Greg Lynn FORM) -

Some have understood though, like Marcel Wanders with his Knot Chair.

That was a very smart way of understanding how to make a flexible thing rigid. What I’ve found is that there are a couple of really huge ideas in composites, like locating structure in load paths rather than consolidating structure into a frame and disengaging the structure from the lineaments defining a form. If you use the character of the material in all those ways, it not only becomes really practical but there is also a whole language of design that comes out of it. Another problem with the use of carbon in particular and composites in general is that, until 2009, building codes viewed composites as finishes, so the only way to use them without running your own tests was to use them decoratively. Most architects attempt to use carbon either like a steel frame or like a material swatch that’s purely decorative.

Interior furniture being installed between the carbon composite bulkheads in the main hull of the GF 42 trimaran. (Photos courtesy Greg Lynn FORM)

-

»A wood-framed building is more toxic with a larger carbon footprint than an actual carbon fibre building.«

Custom-made furniture elements for Greg Lynn’s GF 42 trimaran. (Photo courtesy Greg Lynn FORM)

-

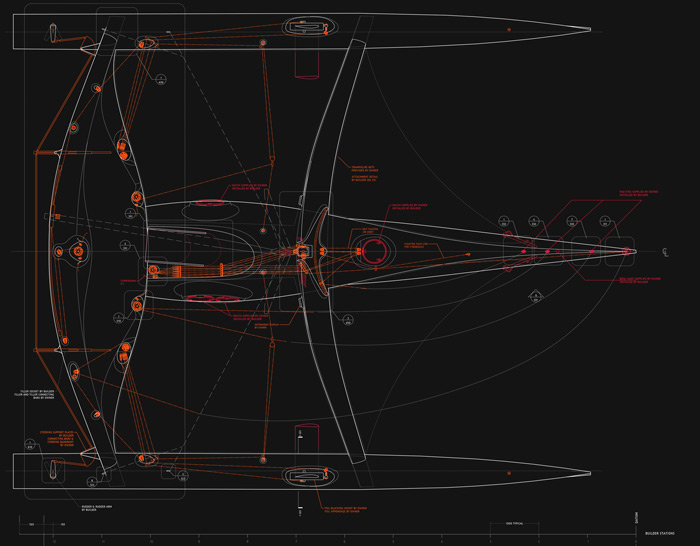

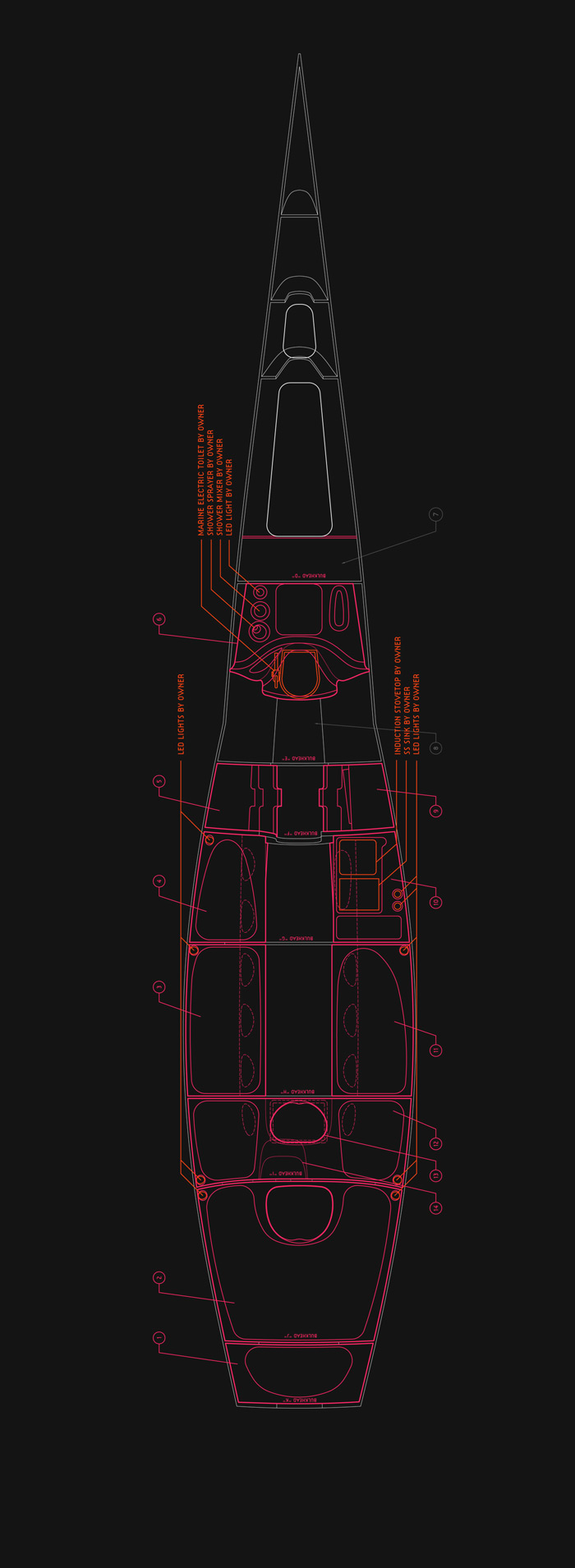

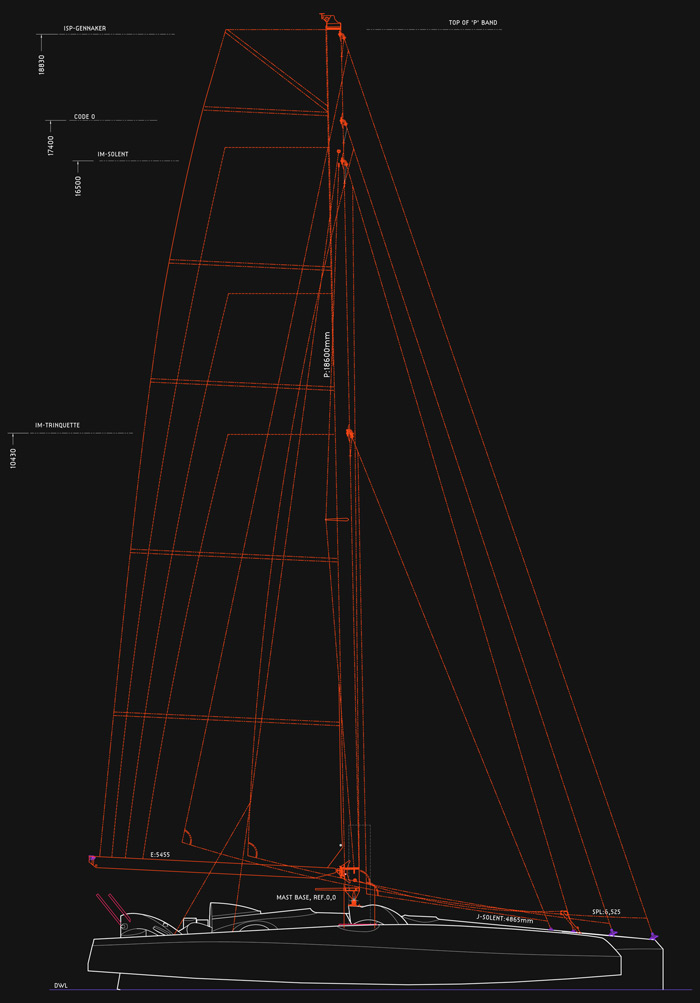

Deck plan, interior plan, and sail plan of Greg Lynn FORM’s new trimaran, the GF 42, due for completion in January 2014. (Images courtesy Greg Lynn FORM)

-

Greg Lynn, born in 1964 in Ohio, is head of Greg Lynn FORM, an architecture firm based in Venice, California, known for its boundary-breaking, biomorphic shapes and embrace of digital tools for design and fabrication, with projects such as the New York Presbyterian Church in Queens. He studied architecture and philosophy at Miami University of Ohio and later took an MA in architecture at Princeton University. Lynn has taught at several universities around the world including The University of Applied Arts, Vienna; ETH Zurich; University of California, Los Angeles, Department of Architecture and Urban Design; Yale School of Architecture; and Columbia Graduate School of Architecture Planning and Preservation. In 2008, he won the Golden Lion at the 11th International Venice Biennale of Architecture.

I read somewhere that you are good at predicting the future. How do you see our future as carbon-based life-forms in terms of our relationship with carbon as a material. Do you think we are going to move towards a more biological, organic relationship with our environment?

I’ve never tried to predict anything because I find it very tough to do, but I have had some success in influencing the field, in particular with digital technology. I see potential for my own exploration in the design of large-scale composite structures and I will publicize and explain the principles and possibilities to my colleagues and students as clearly and concisely as I can in the hopes of speeding their adoption. Over the last several years I have invested a lot of time, energy and money into mastering composite design and construction. We are even making composite parts and prototypes right in my office. I co-designed an ocean-going trimaran with Frederic Courouble and we built much of the tooling for it, as well as the carbon interiors and details that I built and supplied directly to Westerly Marine, one of a handful of builders in the world experienced in high-performance carbon yacht construction. I initiated the project mostly because I am interested in the challenge of using state-of-the-art software and construction to design a building-sized object that is under thousands of pounds of load moving at high speed, converting the wind into motion.

So you are saying that working with composites has fundamentally changed how you think about architecture?

Yeah sure, like Marcel did with that chair: it’s a macramé chair rethought with new chemistry. I look at everything totally differently now, through a cloth lens. So rather than trying to make wood behave like steel, which is what Richard Neutra and other modernists did, now I see wood behaving like, say, wicker or woven rattan. My personal design paradigm has changed. p

-

Search

-

FIND PRODUCTS

PRODUCT GROUP

- Building Materials

- Building Panels

- Building technology

- Façade

- Fittings

- Heating, Cooling, Ventilation

- Interior

- Roof

- Sanitary facilities

MANUFACTURER

- 3A Composites

- Alape

- Armstrong

- Caparol

- Eternit

- FSB

- Gira

- Hagemeister

- JUNG

- Kaldewei

- Lamberts

- Leicht

- Solarlux

- Steininger Designers

- Stiebel Eltron

- Velux

- Warema

- Wilkhahn

-

Follow Us

Tumblr

New and existing Tumblr users can connect with uncube and share our visual diary.

»Less is a bore.«

Robert Venturi

Keyboard Shortcuts

- Supermenu

- Skip Articles

- Turn Pages

- Contents