-

Continental shift

A group discussion about how to reconnect

architecture with AfricaText by Florian Heilmeyer, Illustrations by Lena Giovanazzi

»The question is: what kind of an architect does Africa need?«

Luyanda Mpahlwa (Cape Town)»What we need are people that bridge the gap between the few formal areas and the informal system.«

Thorsten Deckler (Johannesburg)»We don’t even have terminology to talk about these kinds of cities. We need to re-evaluate culture and our language to find words to describe what’s in front of us.«

Angela Mingas (Luanda) -

A symposium accompanying the Afritecture exhibition provided an ideal opportunity for uncube’s Florian Heilmeyer to gather five experts to discuss some of the pressing issues facing architecture across Africa.

Although the participants came from a diverse range of countries, professions and contexts, certain key topics and issues stood out during the week of lectures and discussions accompanying the show: questions of formal and informal structures, of rediscovering or protecting traditional techniques, of education, and of local identity. During the uncube round table discussion, these issues crystallised around the need for entirely new models and ideas for architecture and urbanism. -

LUYANDA MPAHLWA

(Cape Town, South Africa)Luyanda Mpahlwa’s architectural education in South Africa in the 1980’s was interrupted when he was incarcerated for political activities against apartheid. As an exile in Germany, he later completed his architectural degree at Technische Universität Berlin. In 2000, Mpahlwa moved back to his native South Africa, where he founded the MMA Architects studio in Cape Town. In 2009, he established his own design practice, Luyanda Mpahlwa DesignSpaceAfrica. He is the recipient of the South African Institute of Architecture Award of Excellence for the South African embassy building in Berlin. Mpahlwa was the first African ever to be awarded the International Curry Stone Design Prize in 2008. Another career highlight was his role in the technical committee team organising the 2010 World Cup in South Africa.

designspaceafrica.com

Florian Heilmeyer // I was relieved that during the discussions over the last two days there was no attempt to summarise a “typical Africa” or to identify any Pan-African trends. For me the many different projects, ideas and perspectives from many different African countries are clearly connected to current issues being discussed worldwide. The problems of economic growth, rapid urbanisation, rapid social transformation and weak political structures are shared not only between African countries but around the globe. Yet there are also specific shared approaches to be found in your work. Could it be said that you’re all trying to understand and upgrade older techniques in order to revive them in the face of globalised concepts of Modernism?

Luyanda Mpahlwa // In a very general way I’d say yes. We still need to connect architecture with Africa. Most of what we have learned in the universities in Africa is not applicable in practice; it fundamentally misunderstands how Africa works. In the village where I was born in South Africa, there is no architect or engineer – but people know how to build. They learned to build from their parents, who learned it from their parents. This culture of building one’s own house continues today in many African cities, but over time this understanding has been lost in the face of Modernist planning methods. We now have the opportunity and the responsibility to reconnect people with local building conditions and knowledge.

»Do we need an ‘African architect’? No. We need to empower local people to make them part of the solution.«

-

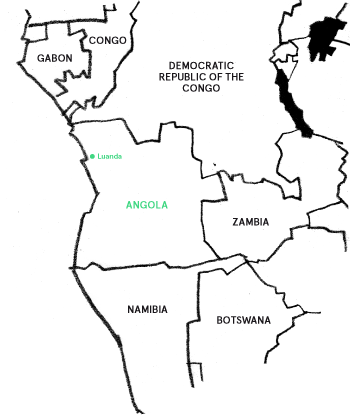

Empty Promise: Thirty miles from Angola‘s capital of Luanda, Nova Cidade de Kilamba was built by the China International Trust and Investment Corporation to house half a million residents – who have yet to arrive. Though governmental subsidies may finally be enticing people to buy homes, the few people to be seen there are still mostly guest workers brought in to maintain its empty grounds. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

-

NAEEM BIVIJI

(Nairobi, Kenya)Naeem Biviji studied architecture at the University of Edinburgh where he graduated in 2004. He has worked for HCP in Ahmedabad, India, and as a furniture maker in Kenya and Scotland. In 2005, in collaboration with Bethan Rayner, he co-founded Studio Propolis in Nairobi, Kenya. Operating across disciplines and scales, their approach to architecture combines studio-based design work with a direct involvement in the process of making. Studio Propolis is involved with a broad range of work from design and built architecture projects to prototyping and manufacturing custom furniture and joinery. Work includes institutional buildings, houses, gallery spaces, mass seating solutions and one-of a kind pieces of furniture.

www.studiopropolis.com

Naeem Biviji // I agree. In Kenya, where I have lived and worked since 2005, there is no culture of building anymore, it seems to have died out. As an architect I feel impotent to do anything in an environment crippled by unchanging planning laws and regulations. Due to rapid globalisation the markets are flooded with cheap materials, products and systems, and the skill level of many workers in Kenya is very low. We need to build up local industry, train people and re-integrate older materials and techniques.

Florian Heilmeyer // And to revive the culture of building without architects?

Luyanda Mpahlwa // When I say people don’t need architects in Africa, I don’t mean that architecture is unnecessary. The question is: what kind of an architect does Africa need?

-

What tools do we need to make architecture accessible and to connect it to the skills within our many different cultures? Architecture cannot create an appropriate environment without connecting to local culture, but at the same time these cultures are changing fast. People working in cities are now used to a certain lifestyle and infrastructure. The traditional is considered anti-modern, poor and antiquated. Even the South African Rondavel, typical round huts with pitched roofs, are disappearing.

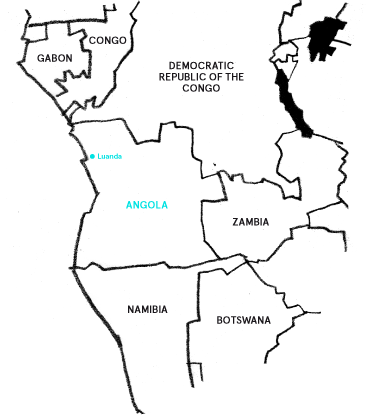

Andres Lepik // In 2011 the government in Rwanda officially prohibited thatched roofs, even in the smallest villages. They have to be replaced by corrugated iron because the president decided that thatched roofs are no longer “decent architecture”.

Angela Mingas // I was born in Angola and studied architecture in Portugal, Spain and the UK before I returned home. My friends and I were unsatisfied with architecture education in Angola, so we founded the second private architecture school in Luanda. We try to address the question of what architecture and urbanism in Angola are today. If we can look at Luanda in an unbiased way, this city is a laboratory breeding all kinds of different forms of urbanity, formal, informal and everything in-between. But how can we develop an unbiased approach if terms like “formal” and “informal” already evoke wrong associations and images? At our university we discuss new urbanisms with a broad range of people from different backgrounds, like sociologists, economists, politicians, philosophers, and poets. We want to really understand how Luanda works, and only then can we develop methods for improving real living conditions.Florian Heilmeyer // Thorsten, you were born in Namibia, studied in Johannesburg and went abroad to work in the Netherlands with OMA on projects in Asia and Europe. In 2004 you returned to South Africa. What was it like to come back to Johannesburg?

Thorsten Deckler // Johannesburg is also a laboratory. You cannot separate architecture from urbanism there. Johannesburg educated us as we started to explore and analyse the unknown territories of the informal settlements. Well, at least they were unknown to architects! Statistics say that only five per cent of the built environment in Africa is formal planning.

-

Forced Modernisation: Rwandan “nyakasi”, the traditional round huts with thatched roofs, are becoming obsolete across the country as the central government pressures residents to replace the thatching with corrugated sheet metal, one of various “forced modernisation” schemes. Though more reliable for rain-protection, metal roofs are not appropriate for the climate and they are unsustainable since residents cannot repair them individually. (Photo: Melanie and John Kotsopoulos)

-

ANGELA CHRISTINA MINGAS

(Luanda, Angola)Angela Christina Mingas is both director of the CEIC Arquitectura (Centre for Studies and Scientific Research) and the FCT (Faculty of Technological Sciences) at the University Lusiada of Angola. Since 2004 she has held different positions at this institution in her primary fields of expertise, including architecture, pedagogy and academic administration. In 2013, she received her PhD from Universidade Lusiada, Oporta, Portugal. Mingas gained experience as an architect and consultant in various venues, both private and public. For the Expo Zaragoza 2008 she was on the technical sub committee for the Angola pavillion, and from 2009 to 2011, she was the technical consultant to the Council of Ministers of the Republic of Angola in Luanda.

»We try to help a new generation of architects to develop pride in their roots as Angolans, as Africans, as humans and as architects.«

This leaves 95 per cent to what we call “informal” – so why do we distinguish between the two at all? Both are valid and architects have to be able to work with both commercial and informal architecture.

Angela Mingas // The term “informal” makes no sense; informal is only classified as such because formal planning is unable to deal with different forms of urbanity. We don’t even have terminology to talk about these kinds of cities. We need to re-evaluate the urban culture and our language to find words to describe what’s in front of us. To address this we recently started a new course at our school where we try to invent a form of urbanity based on Bantu philosophy.

Thorsten Deckler // Architects often complain about their increasing irrelevance, which is ridiculous. We can’t focus on the five per cent of formal structures and call our work relevant. -

THORSTEN DECKLER

(Johannesburg, South Africa)Thorsten Deckler studied architecture at the University of Witwatersrand, Johannesburg. He has worked for OMA/Rem Koolhaas on projects in Europe and Asia, where he gained international working experience. In South Africa, Deckler worked together with Peter Rich on rural developments. He operated his own architectural practice for three years before joining forces with Anne Graupner to co-found 26’10 south Architects. Their work focuses on the various contexts of the city. Projects range from large-scale works to housing, from private residences to building conversions. Exhibitions, art installations and community events represent another line of their architectural services. 26’10 initiated an independent research project which investigated the “Informal City”. In 2012, the office was selected as the best emerging practice in South Africa.

www.2610south.co.za

»Only five per cent of the built environment in Africa is formal planning. This leaves 95 per cent to what we call ‘informal’ – so why do we distinguish between the two at all?«

In most African cities there is no way formal planning methods could ever get control over the incredible speed of development. What we need are people that bridge the gap between the few formal areas and the informal system, which breaks every rule you learn in university. We have to humanise our cities starting from what is already there. Even in South Africa, where modern town planning was used to establish a racist political system of control and segregation, it is incredible to see the potential of the townships to grow into real, liveable cities now. Unfortunately I see that our universities are still sticking to their old conservative concepts.

Florian Heilmeyer // Baerbel, you have worked at the University of the Applied Arts in Vienna since 2002 and you have frequently brought your students to Ghana and the DR Congo.

-

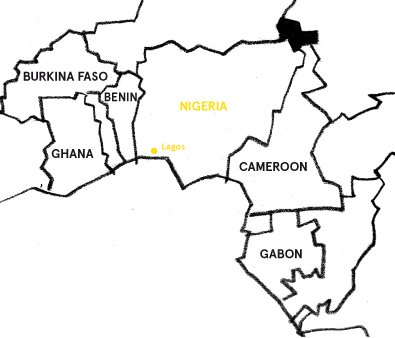

Fish Out of Water: Luanda‘s New Assembly Hall was completed in 2013. Designed by the Beirut-based DAR Group and constructed by the Portuguese company Teixeira Duarte, its resemblance to early 1900s colonial architecture represents the privileging of imported architecture styles ill-suited to local context. With no public competition, let alone pause for reflection, the whole building was built from prefabricated panels shipped to Luanda and slapped together in six weeks. (Photo: Sheenagh Burrell, almalink.org)

-

BAERBEL MUELLER

(Vienna, Austria)Baerbel Mueller founded nav_s baerbel mueller (navigations in the field of architecture and urban research within diverse cultural contexts), which has focused on projects in Ghana and the Democratic Republic of the Congo since 2002. She is assistant professor at the Institute of Architecture (IoA) at the University of Applied Arts Vienna, and professor at the New Design University in Sankt Pölten, Austria. From 2002 to 2011, she taught at the studio of Wolf D. Prix, directing student realisation projects and interdisciplinary courses. Since October 2011, she has been the head of the IoA (applied) Foreign Affairs Lab, which investigates spatial and cultural phenomena in rural and urban Sub-Saharan Africa through research-based workshops and field trips.

www.nav-s.net

How do you prepare the students for working in such a very different context?

Baerbel Mueller // I’m always asked whether it is different to work in Austria than in Ghana. In general terms, it isn’t – architects should always try to understand the given context of a project, in Europe and in Africa alike. Of course, the local circumstances are always very specific. In some places in Africa people don’t even understand what an architect is and you are always identified as an engineer. But it doesn’t matter what you are called. You face a task, you start a dialogue, and you build trust. It’s like being a politician, in the sense that you are a choreographer of many processes, trying to find spatial responses.

Luyanda Mpahlwa // It was interesting to return to South Africa after nearly 15 years away. My home country had changed so much that I almost had an outsider’s view.»It’s like being a politician, in the sense that you are a choreographer of many processes, trying to find spatial responses.«

-

At university in Berlin I was trained to look at context, history, politics, and culture. Can “African architects” solve all the problems? No. We need to empower local people to make them part of the solution. That being said, direct participation is not the solution to every task; that is a trap. We must analyse the context and find the right strategy, which is sometimes participatory and sometimes not. And universities are fundamental; young architects must learn that architecture is not about starchitecture or glossy images for magazines. I had to go to Berlin to find teachers that were interested in the traditional techniques of Africa.

Angela Mingas // It’s also a question of pride. When my students graduate and face the market, they come back to me say, okay, I see the advantages of traditional materials and techniques, but my clients don’t want to live in an adobe house. Just recently a huge factory for cement bricks in Luanda was officially opened and the Minister of Building said on national television: “This is a great moment in the history of Angola because we are finally leaving adobe architecture behind us”. Unbelievable! The majority of politicians are very prejudiced about their own cultural heritage, they see it as something uncivilised, as if they were ashamed. We try to help a new generation of architects at our university to develop pride in their roots as Angolans, as Africans, as humans and as architects. In Europe you get the title of “architect” after studying for three years. In Angola, we will also teach you art, philosophy, sociology, and literature. That’s what you need as an architect there.

Thorsten Deckler // We are blinded by the images that flood over us every day on television and the internet. When we approach people in the townships of Johannesburg and ask them how they want to live, they start drawing a villa like they’ve seen on television. They live in a shack with eight people on 40 square metres or less, but they dream of a villa. How does one find common ground around what is achievable?Florian Heilmeyer // Listening to all of you over the last days I am not sure if I should be optimistic because of the many ideas and projects that seem to be going in the right direction – or pessimistic because of the diversity of simultaneous challenges. How about you, are you optimistic or pessimistic?

Angela Mingas // I don’t know. In Angola there is a lack of a vision for the future.

-

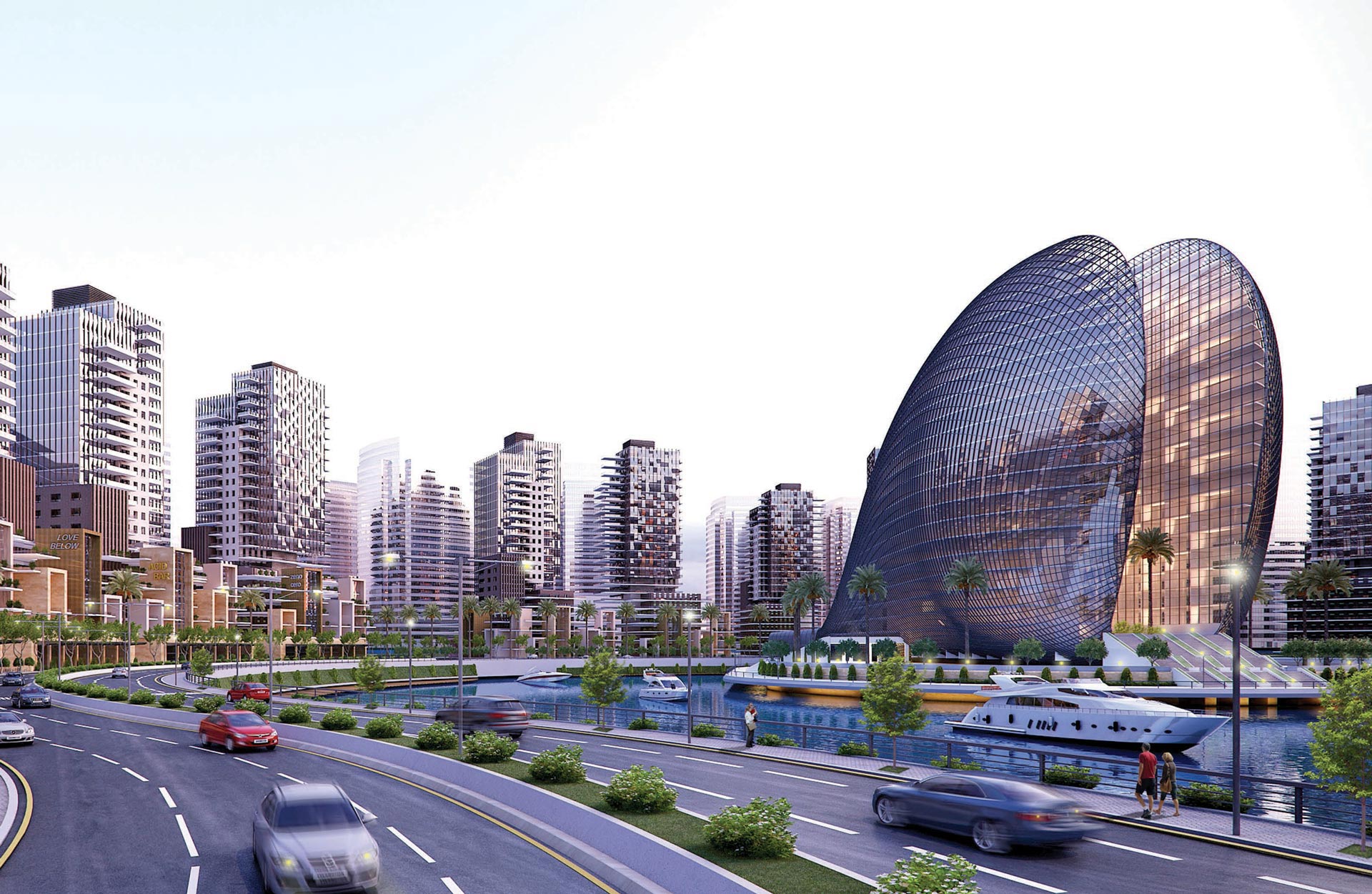

Dubai Chic: “Rising like Aphrodite from the foam of the atlantic!” Eko Atlantic, “the new financial centre of Nigeria”, is a planned district of Lagos funded by international banks and private investors, slated to house a quarter million residents and 150,000 employees. This Dubai-like investment bonanza will not only generate a business-tourism industry and a lower class of underprivileged guest workers, but also reverse coastal erosion! Eco-friendly, indeed. (Image courtesy Eko Atlantic)

-

Most of what’s happening is only a quick reaction to the most urgent challenges. We must solve so many problems at the same time that its hard to develop any long-term plan. We still have not the slightest clue what an urbanism or an architecture of an independent Angola could look like.

Naeem Biviji // It is a complex challenge, but that is exactly what makes me optimistic: there is so much work to be done everywhere and so many creative people working at the same time to find possible answers.

Luyanda Mpahlwa // I think Africa will need a long time to answer these questions. Architects in Africa are still operating on a rather small scale while all these Dubai-isms, Shanghai-isms, whatever-isms are happening. Politicians and companies are still trying to solve African problems with models they’ve seen in other places. But modern skyscrapers of glass and steel will not solve the problems.

Thorsten Deckler // Am I optimistic about Johannesburg’s future? I don’t know. It’s a city that’s fast and harsh and diverse and changing all the time. Nothing that I’ve learned in university seems to apply here. Our tool kit has to be constantly updated, and we have to be very creative about this. That’s what makes it so interesting, exciting and challenging.

Baerbel Mueller // I agree with Naeem: there is enormous pressure and potential with all these developments happening at the same time. So there are many opportunities, and we need to be very creative.

Angela Mingas // You are right that there are many opportunities. But Luanda is in a terrible state and sometimes I feel like if we were doctors, we would have to attest that it is a dying body. I’d rather be training an athlete. I would like to turn Luanda into Usain Bolt, but instead we are tinkering around with all these symptoms of death. It can be so depressing. We must have the strength to look at this dying body and still imagine it as an athlete.

Naeem Biviji // Yes. Imagine the athlete.

-

Search

-

FIND PRODUCTS

PRODUCT GROUP

- Building Materials

- Building Panels

- Building technology

- Façade

- Fittings

- Heating, Cooling, Ventilation

- Interior

- Roof

- Sanitary facilities

MANUFACTURER

- 3A Composites

- Alape

- Armstrong

- Caparol

- Eternit

- FSB

- Gira

- Hagemeister

- JUNG

- Kaldewei

- Lamberts

- Leicht

- Solarlux

- Steininger Designers

- Stiebel Eltron

- Velux

- Warema

- Wilkhahn

-

Follow Us

Tumblr

New and existing Tumblr users can connect with uncube and share our visual diary.

»Architectural interpretations accepted without reflection could obscure the search for signs of a true nature and a higher order.«

Louis Isadore Kahn

Keyboard Shortcuts

- Supermenu

- Skip Articles

- Turn Pages

- Contents