-

Memories

of the

Moon

AgeA Lunar love affair

by Lukas Feireiss

The 1952 Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade in New York, featured the Spaceman, a tribute to growing Lunar lunacy in the USA. (Photo © Bettmann/CORBIS)

-

For centuries humans have been fascinated by space travel and visiting other planets. Our nearest astronomical neighbour, the Moon – just three days away by rocket – still serves as an object of creative projection and speculation to visionaries across the globe. It has been nearly four decades since the first moonwalk, making today a good moment to trace a selective history of Lunar exploration. Lukas Feireiss explores space travel to the Moon as the ultimate flight of fancy for the human imagination and testing ground for ideas in reality.

Born to a mercenary and a herbalist who was later tried for witchcraft, the German mathematician, astronomer and astrologer Johannes Kepler produced the first literary science fiction about our planet’s only natural satellite, the Moon. Published four years after Kepler’s death in 1634, his fantasy novel Somnium (Latin for “The Dream”) presents a detailed imaginative description of how the Earth might look when viewed from the Moon, and is considered the first serious scientific treatise on Lunar astronomy.

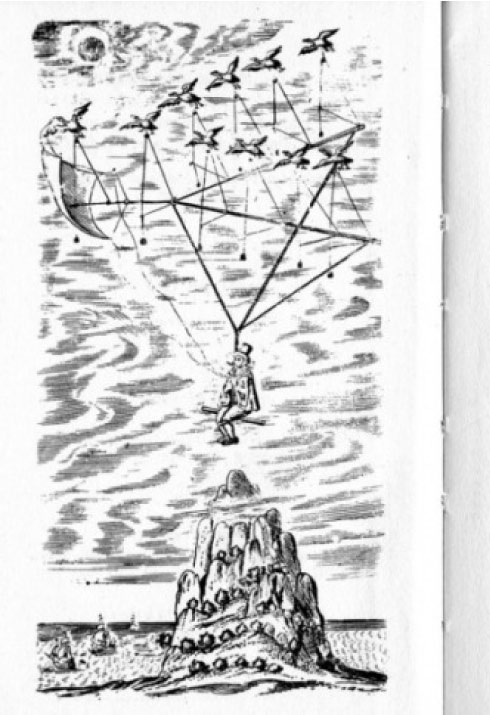

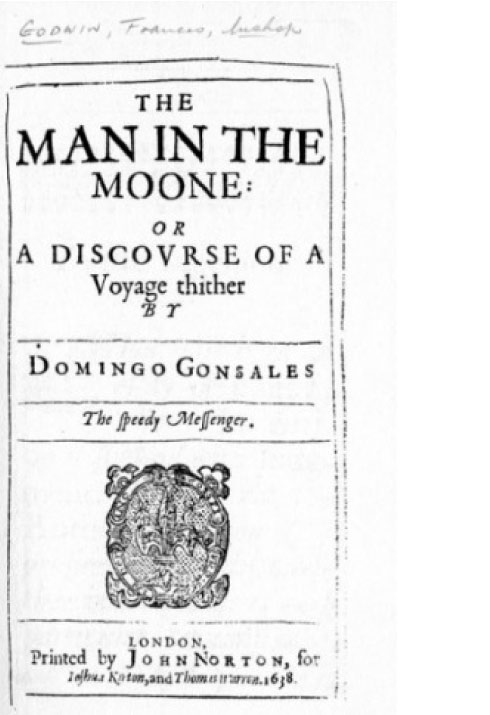

The pseudonymous, posthumously published novel The Man in the Moone (1638) by English bishop Francis Godwin is also considered one of the first works of science fiction. This fantastic voyage of utopian discovery tells the story of a man who flies to the Moon in a chariot towed by geese, encountering an advanced Lunar civilisation. Both books, written by key figures of the seventeenth-century scientific revolution, had an enormous impact on the European imagination for centuries after their initial publication.

-

Frontispiece and title page of the first edition of “The Man in the Moone or the Discourse of a Voyage” by Domingo Gonsales, 1638.

Yet the true pioneer of the space age undoubtedly remains French novelist, poet and playwright Jules Verne with his seminal novel on space travel From the Earth to the Moon (1865) and its sequel Around the Moon (1870). The two books tell the story of an attempt to build an enormous sky-facing space gun and to launch three people in a projectile towards the Moon. Verne’s rich imagination paired with scientific accuracy has fuelled the realms of both science and the arts ever since.

French illusionist, innovator and pioneer filmmaker George Méliès’ 11-minute silent film The Trip to the Moon is loosely based on Jules Verne’s space travel novels and also H.G. Wells’ The First Men in the Moon (1901). Méliès was the first to translate the dream of manned space travel into moving images, and showed the possibility of what the Earth might look like from the Moon.

Meanwhile, French astronomers Maurice Loewy and Pierre-Henri Puiseux spent the years between 1894 and 1909 making a complete series of detailed photographs of the Moon and the Lunar surface. Their L’Atlas Photographique de la Lune, published in 1910, is considered the finest and most meticulous documentation of the Moon until the advent of space probes in the 1960s. The Moon’s craters Loewy and Puiseux are named after them.

In 1919, the theoretical basis for future NASA Moon landings was set by a visionary 22-year-old Ukrainian engineer and mathematician called Yuri Vasilievich Kondratyuk.

-

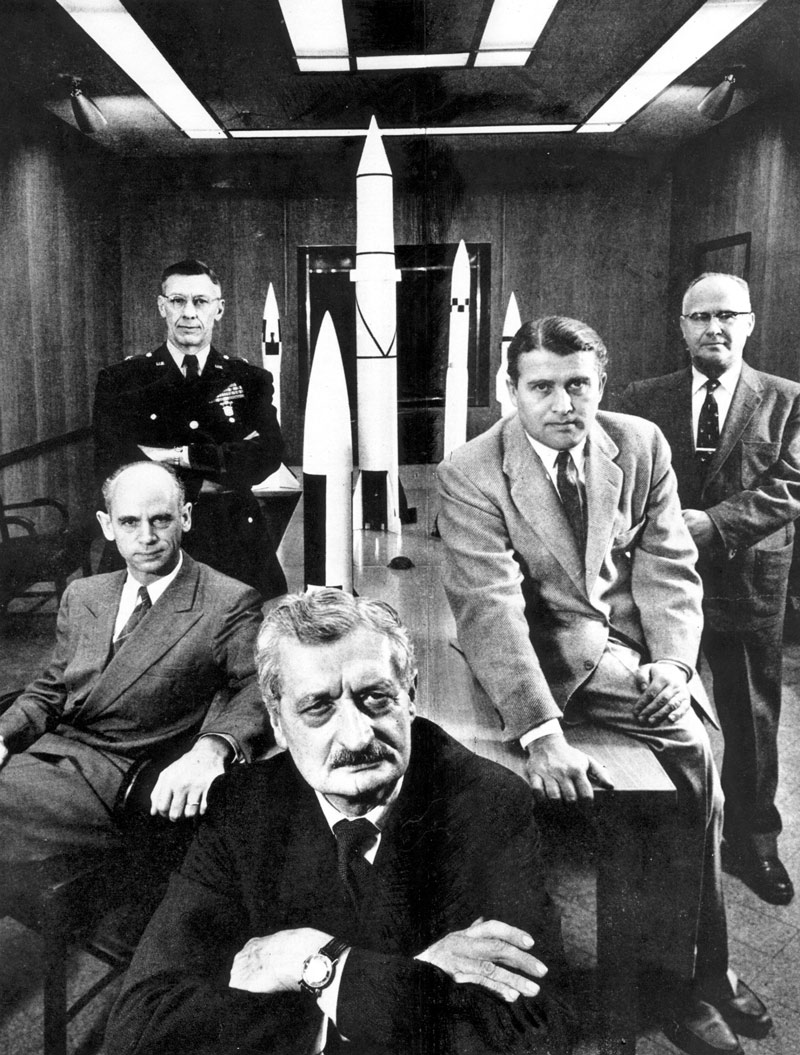

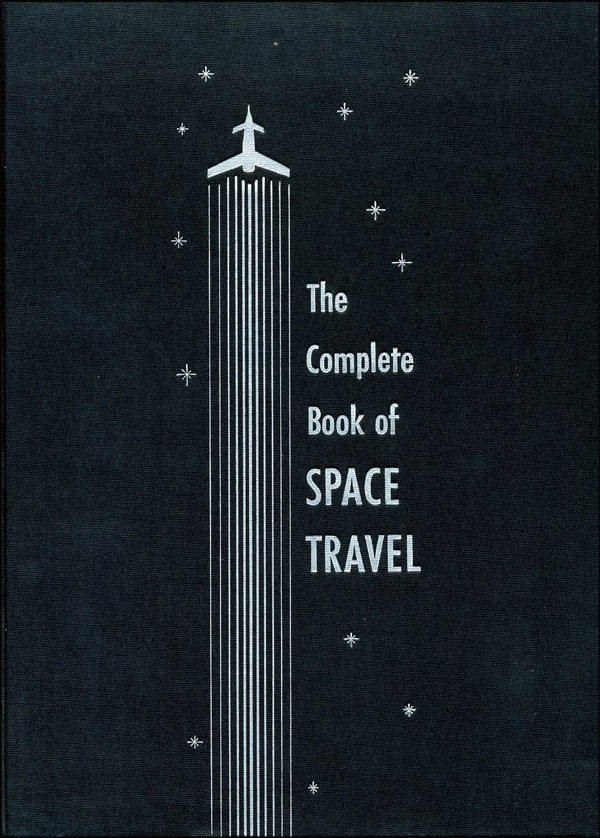

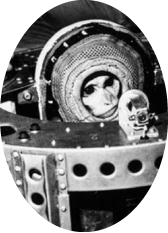

Early space travel research and development was funded by the military: infamously with the development of the V2 rocket by Wernher von Braun and his team during WWII , most of whom were coopted by NASA – seen here, with von Braun centre right, in Huntsville, Alabama in 1956. (Photo: NASA); whilst during the Cold War in 1961, Russian cosmonaut Yuri Gargarin became the first man in space (Photo: ESA). Despite its beginnings, the space race incited the public imagination: here, a Vintage Moon Rocket from Modern Toys, 1950s (Photo: Etsy); the Space Happy Coloring Book, 1953 (Merrill Co.); The Complete Book Of Space Travel by Albro Gaul, 1956 (World Pub. Co).

-

In For Those Who Shall Build, the young theoretician developed the first known Lunar Orbit Rendezvous (LOR), a key concept for a landing and return space flight from Earth to the Moon. When American astronaut Neil Armstrong visited the Soviet Union after his historic flight to the Moon, he collected a handful of soil from outside Kondratyuk’s house in Novosibirsk to acknowledge his contribution to space flight. A crater on the Moon is named after him as well.

Germany 1942, in the midst of World War II, marked the development of a rocket that breached the boundaries of space for the first time in history. The dubious mastermind and “rocket scientist” behind the infamous V2 rocket, Wernher von Braun, went on to work for NASA after the war and literally jump-started the American space programme.

By the early 1950s space travel was part of everyday popular culture. The golden age of space travel arrived before space travel actually became a reality. In the two decades following World War II, fuelled largely by post-war optimism combined with faith in technology and engineering, the possibility of space flight took a firm hold of the public imagination. References to rockets and space travel were everywhere, from television and movies to literature and comic books, toys and games, bubble gum and breakfast cereal.

With the launch of the first satellite Sputnik 1 into Earth’s orbit by the Soviet Union, the twentieth-century space race was officially initiated in 1957. From then on the Cold War rivals, the Soviet Union and the United States, battled for supremacy in space flight capability, ushering in a plethora of new political, military, technological and scientific developments. Less than a month after Sputnik 1, the USSR gave the world its first cosmonaut heroine: Laika, a dog who became the first animal to orbit Earth on board Sputnik 2, only to die after three days due to extreme heat. Laika was not the first, though; before humans went into space, several animals made the trip, including numerous non-human primates in the late 1940s.

Albert I

† 1948

Albert II

† 1949

Dezik

† 1951

Laika

† 1957

Gordo

† 1958

Able

† 1959

-

In 1958, the USA countered with the establishment of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) under President Eisenhower – and in the 1960s the space race reached a whole new level. On 12th April 1961 the Soviet pilot and cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin became the first human to orbit the Earth. A month later he was followed by Alan Shepard, who became the first American astronaut in space. Soon after, the goal of manned space flight to the Moon was set by John F. Kennedy in his legendary “We choose to go to the Moon” speech at Rice University on 12th September 1962. Over the following decade, humanity displayed its ingenuity and ability to overcome the seemingly impossible and showed itself powerful enough to conquer even the force of gravity.

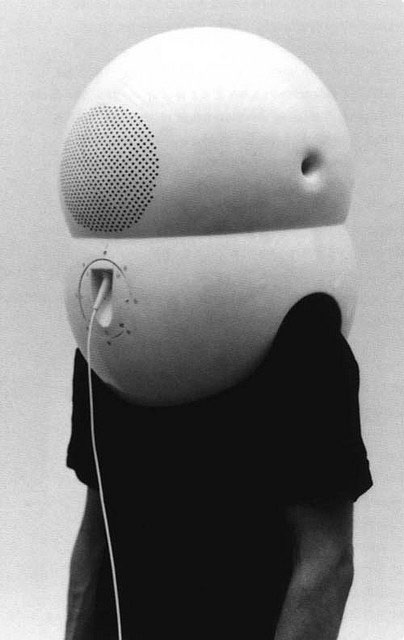

The invention of the spacesuit, in particular, offered a supreme example of the newly discovered possibilities in the provision of basic, stand-alone shelter and protection beyond Euclidean space. It was no coincidence that individual and apparently floating pneumatic spaces arose as the signature forms of a novel, autonomous architecture around the same time.

Haus-Rucker-Co, “Mind Expander” series, 1967-69. (Photos courtesy Haus-Rucker-Co)

Walter Pichler, “Small Room, Prototype no. 4”, 1967. (Photo: Werner Kaligofsky © Generali Foundation, courtesy Galerie Elisabeth & Klaus Thoman Innsbruck/Wien)

-

Stewart Brand’s 1968 “The Whole Earth Catalog” cover and button, and a 1968 NASA Apollo 8 image of the “Earthrise”.

In 1966, the American writer and counterculture activist Steward Brand initiated a public campaign to have NASA release a satellite image of the entire Earth as seen from space, this first photograph, called Earthrise, later adorned the first edition of his infamous Whole Earth Catalog in autumn 1968.

Brand regarded the image as a powerful symbol, evoking a sense of shared destiny and responsibility for all mankind. In the same holistic vein, Buckminster Fuller’s Operating Manual for Spaceship Earth, published the same year and available via Brand’s catalogue, compared the planet to a spaceship flying through space: a spaceship with a finite amount of resources that cannot be resupplied.

At the same time, American filmmaker Stanley Kubrick uncannily anticipated the iconographic power of manned space flight per se with his enigmatic science fiction masterpiece 2001: A Space Odyssey.

On July 20th 1969, the dream was finally accomplished. NASA astronauts Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin, and Michael Collins were rocketed to the Moon. While Collins remained in Lunar orbit in the command spacecraft, Armstrong and Aldrin landed their Lunar Module on the Moon itself. Broadcast on live TV to a worldwide audience of an estimated one-fifth of the Earth’s population, Armstrong’s famous words: “That’s one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind” and his photo of Buzz Aldrin on the Moon’s surface quickly became icons of American space exploration.

Kubrick’s cinematic imagination even predates the famous live televised pictures of the Earth and the Moon from Apollo 8, which shook the foundations of human culture, experience and self-perception.

-

Tom Sachs, “Landing Excursion Module”, 2012. (Photo: Graham Judson, courtesy Tom Sachs Studio and Gagosian Gallery, LA)

Walter Cronkite’s famous brodacast of the Apollo 11 Moonwalk, 1969.

(Video: CBS News) -

Foster + Partners’ concept for a Lunar outpost near the Moon’s south pole, 2013. (Image courtesy Foster + Partners).

-

Lukas Feireiss (*1977) is a curator, artist and writer and a graduate of Comparative Religious Studies, Philosophy and Ethnology. His Berlin-based creative practice Studio Lukas Feireiss focuses on the discussion and mediation of architecture, art and contemporary culture in the urban realm. His studio provides overall conceptual development, design and implementation for diverse formats of knowledge dissemination and its visual communication to cultivate cultural reflexivity. He is the editor and curator of numerous books, exhibitions and symposiums and teaches at several universities worldwide.

www.studiolukasfeireiss.com

The Apollo 11 mission effectively ended the space race and fulfilled the goal proposed seven years earlier by President Kennedy to land a man on the Moon and return him safely to the Earth before the end of the decade. Five subsequent Apollo missions also landed astronauts on the Moon, the last in December 1972. In these six flights, 12 men walked on the Moon. The moment that manned space flight became a reality, real life in the late 1960s and early 1970s brought an end to the space frenzy back on Earth. Once the goal had been achieved, the enormous sums spent on the space programme suddenly seemed no longer justifiable against the backdrop of the Vietnam War, race riots, assassinations of civil rights leaders and general political turmoil.

However, the dream of manned space travel to the Moon as well as life on the Moon lingers on and continues to inspire both artists and architects. Perhaps most ingenious contemporary artistic interpretation is Tom Sachs’ Space Program (2007), a life-sized bricolage realisation of the key components of the Apollo programme with a huge, intricately built Lunar module as its centrepiece. The American artist recollects this historic event of collective memory as a custom-made experience from the free domain of public imagination.

The current re-emergence of the space theme across all mass media from newsreels to Hollywood blockbusters is subliminally fuelling the public imagination once more and seems to be preparing mankind for the dawn of a new space age. More then forty years after men first set foot on the Moon, interplanetary space travel has again entered the realm of the achievable. Whilst a Chinese “Jade Rabbit” crawls across the Moon’s surface, commercial space companies like Virgin Galactic, Blue Origin, Bigelow Inc. and SpaceX aspire to realise trips to the Moon by 2043, and the British architecture practice Foster + Partners, together with the European Space Agency, is currently investigating the possibilities of 3D printed Lunar habitations with Lunar soil as building material.

The future was never closer than it is today. Sooner or later, we are going back to the Moon.

-

Search

-

FIND PRODUCTS

PRODUCT GROUP

- Building Materials

- Building Panels

- Building technology

- Façade

- Fittings

- Heating, Cooling, Ventilation

- Interior

- Roof

- Sanitary facilities

MANUFACTURER

- 3A Composites

- Alape

- Armstrong

- Caparol

- Eternit

- FSB

- Gira

- Hagemeister

- JUNG

- Kaldewei

- Lamberts

- Leicht

- Solarlux

- Steininger Designers

- Stiebel Eltron

- Velux

- Warema

- Wilkhahn

-

Follow Us

Tumblr

New and existing Tumblr users can connect with uncube and share our visual diary.

»What the map cuts up, the story cuts across.«

Michel de Certeau: Spatial Stories

Keyboard Shortcuts

- Supermenu

- Skip Articles

- Turn Pages

- Contents