-

Underwater Love

Chris Bosse on water, nature and Frei Otto

Interview by Sophie Lovell

Photo courtesy LAVA

-

Chris Bosse is one of the co-founders of LAVA, the Laboratory for Visionary Architecture, an international architecture and design practice strongly inspired by biomimetics. Bosse was a key designer of the Watercube, the National Aquatics Centre for the 2008 Beijing Olympics. Thanks to his focus on the computational analysis of organic structures, this extraordinary building has a façade that is simultaneously space, structure and metaphor. LAVA was also involved in the transformation of the Watercube into its current incarnation as the Happy Magic Water Park, a playground for Beijing aquaphiles. Bosse spoke to uncube about the giant water baby that made his name.

-

LAVA is known for its rather outlandishly organic architecture, but your work is more than skin deep. How closely do you implement the analysis of natural forms and structures within your buildings?

I love architecture when it has multiple layers of structure, of meaning, of relevance. I don’t like façades that are pure applications to hide an otherwise utilitarian box. When we look at nature, we always try to understand what is going on and translate that into coherent systems. To reconcile this approach with commercial pressures in architecture is not always easy, but in every project we find these moments of magic.

Apart from the fact that the Watercube had a very clearly defined functional brief, how did you arrive at the very watery aspect of the skin and structure?

The Watercube was an attempt to unify wall, roof and floor – structure, skin and space – into one element. We investigated space-packing systems found in nature, turning to corals, foam and soap bubbles. Frei Otto at the Institute for Lightweight structures in Stuttgart taught us to use soap bubbles as a form-finding method for structure and space, and he was a great inspiration. His 1972 Munich Olympic stadium roof is still unsurpassed.

-

Was metaphor intended, or was the design simply a search for lightness and visual impact?

When we started the competition we googled keywords like water, bubbles foam and corals and found intriguing imagery. We mocked up moodboards, which became the guiding visuals throughout the competition. An earlier version of a gigantic wave turned out to be too literal and was rejected in favour of the more subtle adaptation of “cubed” water.

The repurposing of former – incredibly costly – Olympic buildings has become a big theme in recent years. For example, the later downsizing of Zaha Hadid’s Aquatic Centre for the 2012 London Olympics into a local swimming pool, was incorporated into the original construction plan.

Photos courtesy WhiteWater West (interior) & LAVA (exterior)

-

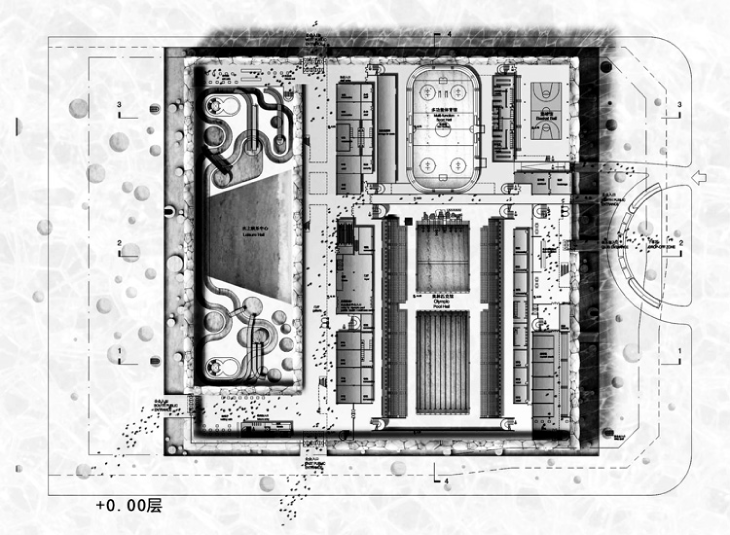

Floorplan image courtesy LAVA. Photo: Ben McMillan.

-

Chris Bosse, Tobias Wallisser and Alexander Rieck founded LAVA in 2007. It was established as a network of creative minds with a research and design focus and has offices in Sydney, Shanghai, Stuttgart and Abu Dhabi. LAVA explores frontiers that merge future technologies with the patterns of organisation found in nature and believes this will result in a smarter, friendlier, more socially and environmentally responsible future. LAVA designs everything from pop-up installations to master-plans and urban centres; from homes made out of PET bottles to “reskinning” ageing 1960s icons; and from furniture to hotels, houses and airports of the future.

l-a-v-a.net

Your office was also involved in the transformation of the Watercube into the leisure facility it is today. Can you describe the process, and are you happy with the changes?

We designed the Watercube from the beginning in two modes: “Olympic mode” and the so-called “legacy mode”, the difference being 12,000 fewer seats. In post-Olympic mode the Watercube turned into restaurants, shops and a gigantic leisure pool full of colourful rides and water games. We weren’t involved in the actual realisation as the building had by then been taken over by the client, but I am quite relaxed about it and happy with how full of life it is now. There are some interesting moments, for example, when a Chinese restaurant meets contemporary architecture, or when Watercube merchandise shops dominate the galleria.

The structure was highly innovative – how is it standing the test of time?

Beijing, of all places, has the potential and the population to draw millions of visitors annually. Reportedly the Watercube is the second biggest tourist attraction after the Great Wall (which I find hard to believe, but that’s what they say). The test of time is always in the maintenance, which they are doing ok. But, most importantly, I think the design is strong and timeless – and now, ten years after the competition, it looks as fresh as ever. I

-

Search

-

FIND PRODUCTS

PRODUCT GROUP

- Building Materials

- Building Panels

- Building technology

- Façade

- Fittings

- Heating, Cooling, Ventilation

- Interior

- Roof

- Sanitary facilities

MANUFACTURER

- 3A Composites

- Alape

- Armstrong

- Caparol

- Eternit

- FSB

- Gira

- Hagemeister

- JUNG

- Kaldewei

- Lamberts

- Leicht

- Solarlux

- Steininger Designers

- Stiebel Eltron

- Velux

- Warema

- Wilkhahn

-

Follow Us

Tumblr

New and existing Tumblr users can connect with uncube and share our visual diary.

»Less is a bore.«

Robert Venturi

Keyboard Shortcuts

- Supermenu

- Skip Articles

- Turn Pages

- Contents