-

Troppo architects: creative pragmatism with a social agenda

By David Welsh

-

Australia is a big place. To travel from where I sit writing here in Sydney, to the northernmost of our capital cities, Darwin, is roughly the same distance as the journey from Berlin to Marrakesh. A lot of different kinds of architecture can develop across distances like this. Any answer to the question of how architecture is made in Australia really depends on the place you’re sitting.

Following their graduation from the University of Adelaide in 1978‚ architects Adrian Welke and Phil Harris moved to the tropical city of Darwin in the far north‚ establishing the firm Troppo in 1980. Darwin had been flattened in 1974 by Cyclone Tracy; as the town rebuilt itself in the coming years‚ the young architects, “armed”‚ as they have said‚ “with a grant to study the history of tropical housing”, found themselves able to offer an alternative to the well-intentioned but questionable cyclone-proof offerings that were shaping the re-born tropical city. Grounded in the lessons learned from common sense – tropical architecture of the past that utilised locally available materials and passive design principles – the partners of Troppo began to experiment with new ways to create responsible regional architecture.

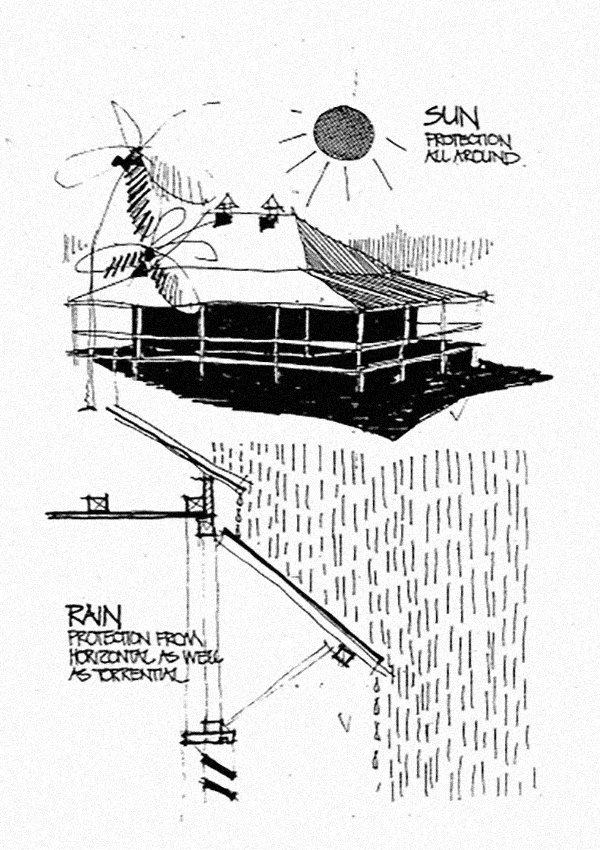

Deriving their name from the term “going troppo”, a phrase that refers to the heat-induced craziness to which inhabitants of the tropics can succumb, the young architects designed their first house in 1982, and named it “the Green Can” after the emerald green can of the Northern Territory’s favourite beer, Victoria Bitter. The result of a low-cost housing competition, the Green Can was a prototype for further models, utilising wide shaded verandahs, a central breezeway and cost-effective, pragmatic materials such as local timber, steel and corrugated iron sheeting.

Previous page: Rozak House, Lake Bennett, NT. (Photo: Patrick Bingham Hall; all images courtesy Troppo)

-

Troppo’s first house, the ‘Green Can’, was designed in 1982, demonstrating their responsive approach to design.

The house gained notoriety, attracting a deluge of criticism from some more conservative local groups, but also attracting more adventurous, like-minded clients who saw a way to live with, rather than in spite of, the local climate. A series of commissions started rolling in for buildings that tapped into not only the material aspects of the tropical regions, but also the social aspects of places where people were willing to chip in and help construct both buildings and the communities around them.

-

Troppo founders Phil Harris (far left) and Adrian Welke (far right) with fellow students Justin Hill and James Hayter.

-

Troppo’s own description of creating “shop drawings for the owner-builder” is an apt description of much of their early work output, where the architect is simply a part of the overall design process, helping to facilitate the involvement of an array of people – clients, contractors, consultants and indeed everyone who uses the building throughout its life.

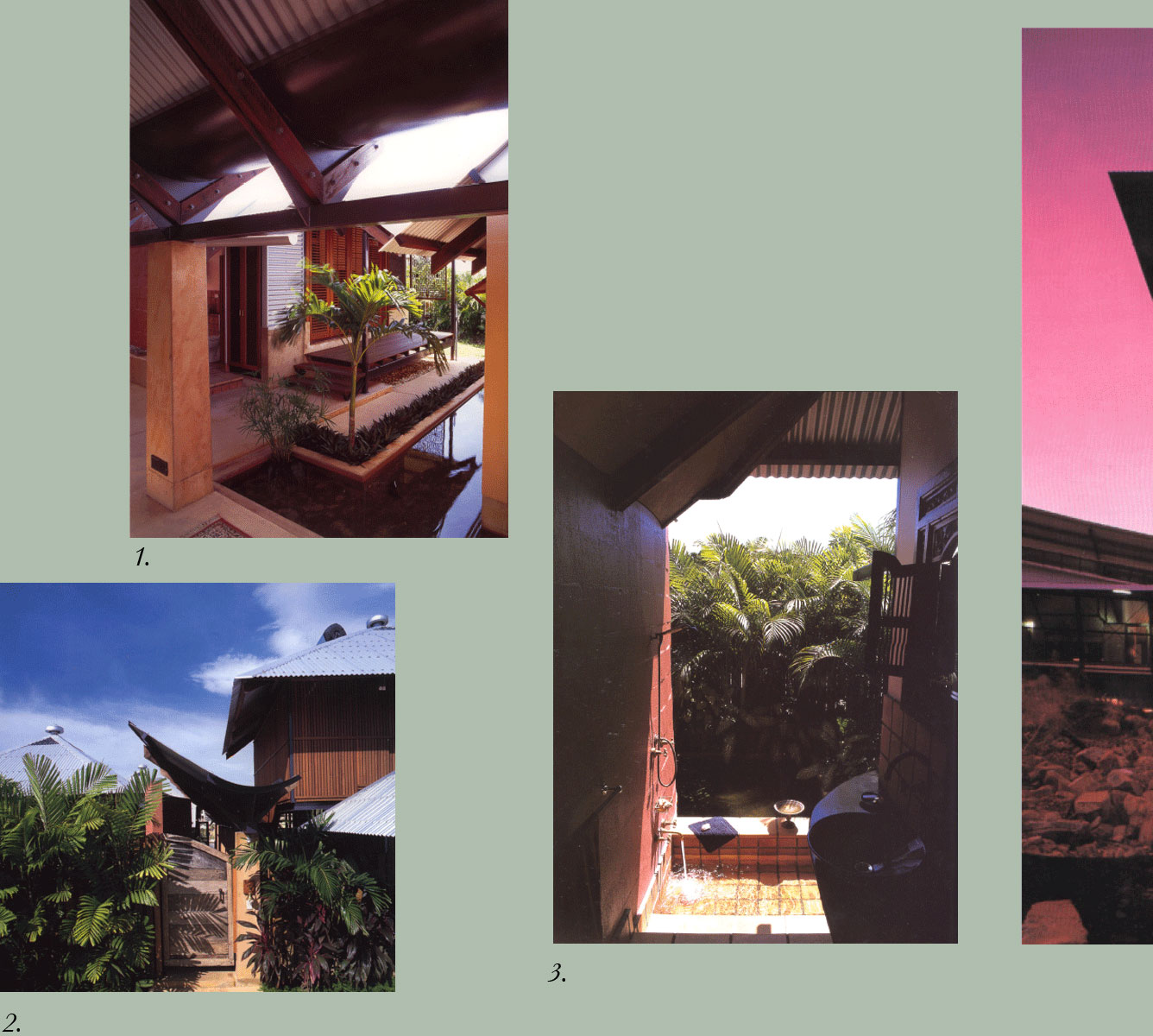

Welke and Harris believe “shelter is about engaging with the environment on your own terms”. Housing examples such as their 1996 Thiel House, where the generosity of a Balinese villa is given their larrikin (meaning mischievous) touch, the twinned pavilion forms of the Rozak House (2002) at Lake Bennett or the Mortlock Lee House (2011), a pavilion house they describe as a building “connecting bush with bush”. These are three examples of the approach where equal attention is given to the environment and the people who live in it.

»Simplicity belies the deep consideration of how a building might exist as part of its environment rather than something just sitting in it.«

-

1. Thiel House‚ Cullen Bay, NT‚ 1996.

2. Garden wall entrance to Thiel House.

3. The open bathroom of Thiel House overlooking the courtyard.

4. Rozak House‚ Lake Bennett‚ NT‚ 2002.

5. The sloping roofs of Rozak House allow for the collection of rainwater. (Photos 1-5: Patrick Bingham Hall)

6. Mortlock Lee House‚ Girraween‚ NT‚ 1996.

7. Verandah at Mortlock Lee House with views across the surrounding stringybark scrubland.

-

Generous deck areas, operable louvred walls and flipped-tin roof forms are just as much about letting the elements in as keeping them out. The forms’ simplicity belies the deep consideration of how a building might exist as part of its environment rather than something just sitting in it.

This critical, regional approach, where climatic engagement is one driver in how an architect responds to a brief, is something Troppo shares with other Australian contemporaries such as Gabriel Poole, Rex Addison, Lindsay and Kerry Clare, Rick LePlastrier and Glenn Murcutt. Most began their practices in tropical regions.

The considerations of context and environment follow in Troppo’s public work as well. Their 1992 Bowali Visitor Centre, designed with Glenn Murcutt, shows all of the climatic considerations of their single housing work.

Bowali Visitor Centre‚ Kakadu National Park, NT‚ 1993. (Photo: Wayne Miles)

-

»Shelter is about engaging with the environment on your own terms.«

Lavarack Barracks‚ Townsville‚ North Queensland‚ 2002. (Photo: Patrick Bingham-Hall)

-

David Welsh is a partner of Welsh + Major Architects, a practice he established in Sydney in 2004 with Christine Major. He has taught at The University of Sydney and the University of New South Wales, and runs masters studios in environmental sustainability and material technologies at the University of Technology, Sydney. He is also a regular contributing writer to design and architecture publications such as Houses, Artichoke and AR Asia Pacific.

welshmajor.com

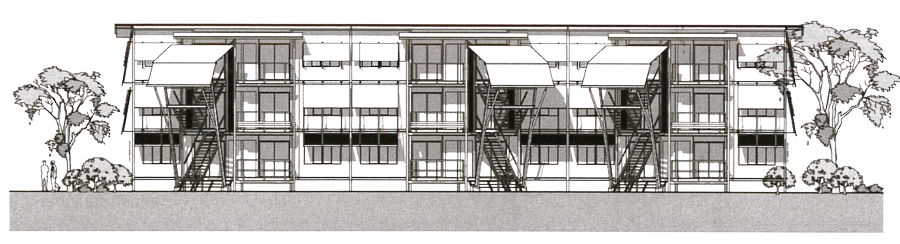

However, some themes, such as the way a building acts as a social symbol and a place for communal gathering, are brought to the fore. The Lavarack Barracks project, completed in 2002 with BVN Architecture, sees Troppo shift in scale again and explore the way large groups of people might come together and engage with each other and their environment.

Troppo’s social agenda is also a key driver in their work. Their practice has done a lot of work over three decades to improve the workability, and livability of buildings in remote indigenous communities. The source of materials and resources has always been at the core of what they do; in these projects in remote locations, the ways that the materials and the buildings get to their site is also just as important in resolving an architectural solution.

“Going Troppo” may have been a way to describe a heat-induced madness, but with the practice of Welke and Harris, it seems the heat and humidity has unlocked their minds to generate a creative pragmatism with a generous social agenda at its (naturally ventilated) heart. I

The external staircases and courtyard of Lavarack Barracks. (Photos: Bligh Voller Nield)

-

Search

-

FIND PRODUCTS

PRODUCT GROUP

- Building Materials

- Building Panels

- Building technology

- Façade

- Fittings

- Heating, Cooling, Ventilation

- Interior

- Roof

- Sanitary facilities

MANUFACTURER

- 3A Composites

- Alape

- Armstrong

- Caparol

- Eternit

- FSB

- Gira

- Hagemeister

- JUNG

- Kaldewei

- Lamberts

- Leicht

- Solarlux

- Steininger Designers

- Stiebel Eltron

- Velux

- Warema

- Wilkhahn

-

Follow Us

Tumblr

New and existing Tumblr users can connect with uncube and share our visual diary.

»Tradition is a dare for innovation.«

Alvaro Siza

Keyboard Shortcuts

- Supermenu

- Skip Articles

- Turn Pages

- Contents