-

Paris Exposition Universelle 1937 and 1939 New York World’s Fair

By Jonas Staal

-

Artist Jonas Staal, whose work deals with the relationship between art, politics and ideology, examines the role of propaganda during two World’s Fairs from the 1930s – a shifting time of extremes of capitalism, nationalism and “democratism” in a world on the brink of war.

Democratism

The world fair model, established in 1851 with the building of the famous Crystal Palace in London’s Hyde Park, embodied the ideal of peaceful, international coexistence among nation states. Each of the national buildings functioned as a cultural embassy, comparable to “gigantic potlatches, joyous ritual displays of richness and power”, in the words of anthropologist and philosopher Raymond Corbey. These peaceful, sanitised, didactic displays sought to prove that the participating nations were capable of engineering civilisation through colonialisation and industrialisation. Western nations established their “democratic” capacity by acknowledging a variety of different cultures in their displays — and then demonstrating that they could manage these cultures.

The world fair modelled the principle of capitalist democracy before it became an established form of governance. The term “capitalist democracy” emphasises democracy not as a neutral framework capable of embracing a variety of different ideologies, but as an ideology in and of itself. “Democratism” is this ideology.

The world fair model highlights three crucial characteristics of democratism: (1) the desire to engineer peaceful coexistence among different cultures and ideologies; (2) a prohibition against questioning the engineering structure – colonial capitalism – upon which this peaceful coexistence is based; and (3) the close collaboration between government and private enterprise.Previous page: Sailors pose in front of the Eiffel Tower, Paris Exposition Universelle 1937. (Photo: gallica.bnf.fr/Bibliothèque nationale de France)

-

Totalitarianism

(Paris 1937)

While democratism is ubiquitous today, the Paris World’s Fair of May 1937 posed a considerable challenge to the sustainability of this form of governance. With Europe on the brink of another world war, the central intention of the 1937 world fair was, according to art historian Dawn Ades, to “shore up Europe’s faith in civilisation… Only in a world fair on this scale would it have been possible for the Spanish Republicans and Nationalists to be present simultaneously.” While we remember the Republican pavilion, since it was the first place where Picasso’s Guernica was publicly displayed, how did Franco’s nationalist military insurgency against a democratically elected government gain a place alongside established nations?Looking from the “House of Italy” towards the illuminated facades of the pavilions representing the USSR (centre) and Nazi Germany. (Photo: gallica.bnf.fr/Bibliothèque nationale de France)

-

The answer: the Vatican. It was thanks to “the Nationalists’ fusion of politics and religion … that the Vatican provided Franco’s side with an opportunity to participate”, inside its own pavilion. What makes this intervention so relevant is not simply the perverse bond between the religious institution of the Vatican and military fascist regimes, but the fact that it lays bare the very origin of the concept of propaganda: its inception can be traced to 1622, when Pope Gregory XV named an anti-Protestant missionary organisation set up by the Vatican the Congregatio de Propaganda Fide, or Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith.

Franco’s creation of a pavilion within the Vatican’s pavilion – even before the city-state itself existed – reveals what is at stake in the so-called peaceful coexistence of nation states at the World’s Fair: a battle for acknowledgement by the key players of democratism. What Franco understood was that, in the context of a world fair, an excessive display of power would undermine his cause. Rather, he simply had to become one among many respected states. His cause was aided by two nations that did not share his concern for subtly and restraint at the fair.

If the decision to place the German and Soviet pavilions in the centrally located International Exhibition was an attempt to enforce the idea of European unity, the effort failed. The Soviet pavilion, designed by architect Boris Iofan, functioned mainly as a pedestal for Vera Mukhina’s enormous sculpture Worker and Collective Farm Woman, depicting two gigantic figures striding forward while holding a hammer (male) and a sickle (female). If these figures were striving toward anything, it was toward the German pavilion, which was directly in front of the Soviet pavilion, across a road.

The role of art as propaganda in capitalist democracy is such a taboo subject precisely because the monumental structures of the 1937 German and Soviet pavilions so violently portrayed what we would come to understand as propaganda. However, it was in their shadow that Franco was able to provide his fascist rule with a sense of cultural respectability. This dynamic reveals how liberal democracy has been historically dependent on “totalitarianism”. .

Our conception of propagandistic art has been restricted to so-called totalitarian regimes, including Fascist Italy and Maoist China. -

Only when hysterical musicals and posters slip through the North Korean border is the word “propaganda” used in a more or less serious manner, yet always with the full conviction that only the most brainwashed of people could be susceptible to the manipulative force of this kind of imagery. This is what I refer to as “propaganda’s propaganda”: the absolute conviction of inhabitants of democracies that their world is lucid, whereas the poor, underdeveloped subjects of Kim Jong-un still naively gather in celebration around images of happy factory workers and peasants. Apart from this being a grave misunderstanding of those subjected to this type of imagery, it is exactly this logic that structures democratist propaganda par excellence: the belief that we are somehow “beyond” propaganda. The idea that there is a clear and absolute historical distinction between totalitarianism and democracy is the core of propaganda’s propaganda.

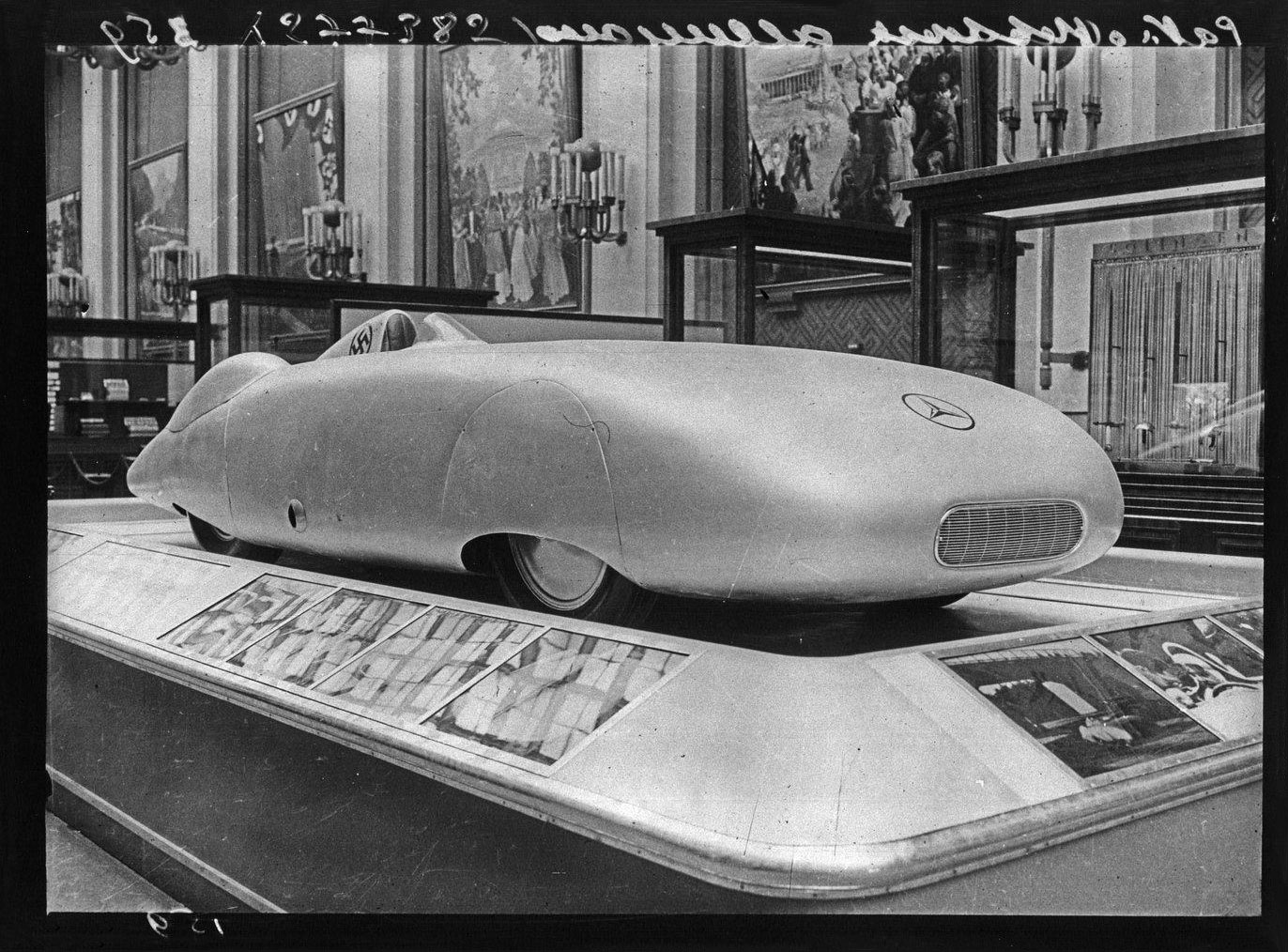

The interior of the German pavilion, replete with lavish treasures; among them a Nazi-branded Mercedes. (Photos: gallica.bnf.fr/Bibliothèque nationale de France)

-

Propaganda

Contrary to what many believe, propaganda was not invented by the Nazis or the Soviets. In fact, Hitler and his propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels based the Third Reich’s propaganda apparatus on Hitler’s own experience in the army during the First World War. Hitler was convinced that the defeat of Germany had been the result of the refined propaganda tactics of the British War Propaganda Bureau, which operated from 1914 to 1917.The “Court of Peace” area at the 1939 New York World’s Fair. (This image and all that follow: New York World’s Fair 1939-1940 records, Manuscripts and Archives Division, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations)

-

This bureau, generally referred to as “Wellington House”, in no way fits the prevailing image we have of propaganda. It did not make agitprop posters, it did not commission gigantic bronze statues and it did not primarily target the masses. Instead, Wellington House developed an intricate network focused on gathering and distributing knowledge to elites in the societies that the British needed on their side. Its main tactic was to never have its actions be recognised as propaganda. It achieved this by giving all the information it distributed an air of academic precision and impartiality. Modern propaganda was thus born in Britain, a supposed paragon of democracy. The aim of this propaganda was to sustain the belief among British citizens that information circulated freely and that public opinion was formed without coercion.

Only two years after the foundation of Wellington House, Edward Bernays, the nephew of Sigmund Freud, was employed by the American president Woodrow Wilson in his own Wellington House: the Committee on Public Information. Bernays later became publicity director for the New York World’s Fair of 1939. In his book Propaganda (1928), Bernays had already considered a different term for the concept of propaganda; due to the negative connotations the word had obtained after World War I, he proposed to refer to propaganda as the “public relations industry”.

Through this concept of public relations, Bernays brilliantly connected the dangers that representative politics posed to democratism, and the risk involved in the blatant exhibition of power by the Nazis and the Soviets at the Paris World’s Fair. He left the concept of propaganda to the “totalitarian” states in order to enforce the sense of an absolute distinction between dictatorship and to the free world. Instead of the overt authoritarianism of dictators, he proposed the idea of an “invisible government”.

What Bernays took from Wellington House was the idea of a far-reaching, invisible infrastructure that could govern society. But instead of seeing this type of “secret governance” as something limited to a state of emergency, Bernays declared a state of total propaganda in both war and peacetime. Moreover, he believed that the problem of total war, as a product of modern technological society, could only be solved by propaganda. Indeed, Bernays considered propaganda the one and only “democratic” way to deal with the unpredictable, anxious masses. The public relations industry’s primary task was to “manufacture consent,” to understand what the masses wanted even before they knew it themselves. -

Democracity

(New York 1939)

Bernays predicted the future of democratism, with the world fair as its prototype. His vision formed the centrepiece of the New York World’s Fair. Entitled “The World of Tomorrow”, the fair featured national as well as corporate pavilions. At the heart of the fair was a massive structure called the Trylon and Perisphere, which at the time was one of the tallest buildings in New York. Visitors entered the construction through an electric staircase, and once inside they encountered a gigantic rotating architectural model of the city of the future: Democracity, designed by Henry Dreyfuss and crafted in accordance with Bernays’s notion of invisible government.The colossal model of “Democracity”, encased within the walls of the Perisphere featured on the cover.

-

The model embodied a utopian urban structure made possible through the replacement of representative government by the corporate rule of the public relations industry. It neatly separated the different needs of its inhabitants into zones, consisting of Centerton (the social and cultural centre), the Pleasantvilles (middle class residential towns), Milvilles (industrial towns), and Farms, with proximity to Democracity’s city centre determined by class position (the Pleasantvilles being the most luxurious and thus the nearest to Centerton). In Democracity’s brochure, writer and cultural critic Gilbert Seldes adopted the tone of real estate promotional materials when he wrote: “If Democracity were Utopia, government would be superfluous…The City of Tomorrow which lies below you is as harmonious as the stars in their courses overhead. No anarchy – destroying the freedom of others – can exist here”.

The resemblances between Democracity and the ideal of the modernist city as elaborated by the Congrès Internationaux d’Architecture Moderne (CIAM), an organisation founded by Le Corbusier [and others] in 1928, are striking. The central premise of the CIAM doctrine is indeed the zoning of the city into different typologies of social activity – such as housing, work, recreation, and traffic. But whereas CIAM planned these social units on an anticapitalist and egalitarian basis, Bernays believed that it was through capitalism – which he considered inherently democratic – that we would arrive at a society of “independent and therefore interdependent men”.

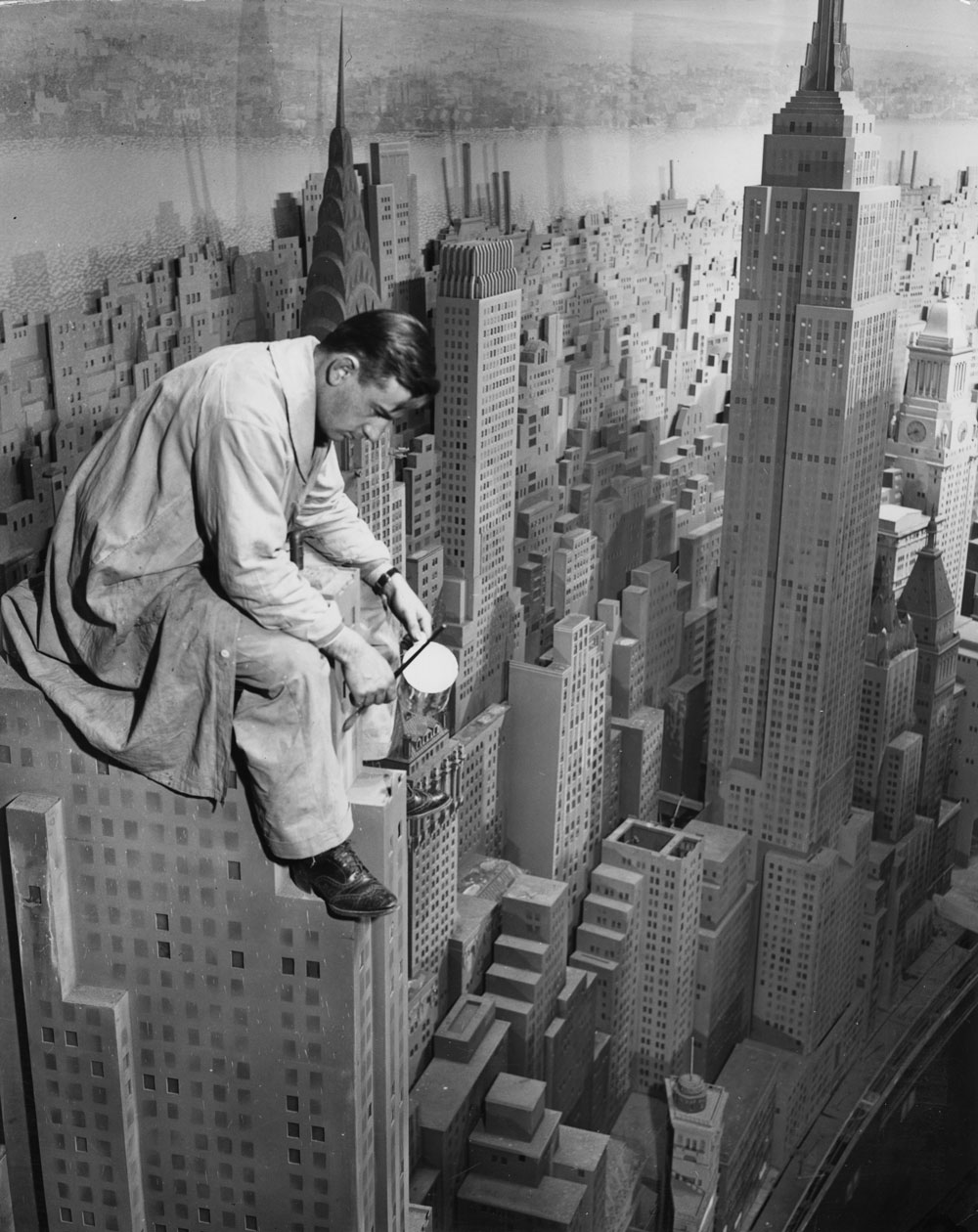

Artist at work on the “World’s Largest Diorama”, the Con Edison “City of Light”

-

Jonas Staal (born in 1981, Zwolle) is a Dutch visual artist and founder of the artistic and political organisation New World Summit. His work deals with the relationship between art, politics, and ideology.

jonasstaal.nl

newworldsummit.euThis is an abridged version of the essay Art. Democratism. Propaganda., that appeared in e-flux journal No.52, 2014 as part of Staal’s project Ideological Guide to the Venice Biennial. Reproduced by kind permission.

The Trylon and Perisphere at the centre of the 1939 New York World’s Fair site.

What Bernays described was basically the replacement of the state by corporations – corporations being natural democratic entities insofar as they can represent the desires of the people in a way that governments cannot. This is crucial in order to understand the governance of the modern democracity, for in actuality it is not a city, but rather a corporation in the form of a city.

This links the 1939 World’s Fair to the planned World Expo 2020 in Dubai: a city engineered by an invisible government of family-owned corporations and public relations industries, which intervenes in the lives of its people only when the construction of skyscrapers and artificial palm-shaped beaches is threatened by strikes or other forms of political organising.

It is hardly surprising that Dubai won the bid to host the Expo. Dubai embodies the world fair precisely as it was originally conceived: a democratic event without parliamentary democracy. At first glance, Dubai seems to exemplify the ideal of a multicultural society. However, Dubai – which is really a corporation in the form of a state led by the Maktoum family – can only exemplify this ideal as long as the ruling structure underlying it remains uncontested. The Maktoum family has dreamed the dream of democratism: to host a world fair that will uphold, through culture and industry, the formal appearance of democracy, without having to actually go through the trouble of elections. I

-

Search

-

FIND PRODUCTS

PRODUCT GROUP

- Building Materials

- Building Panels

- Building technology

- Façade

- Fittings

- Heating, Cooling, Ventilation

- Interior

- Roof

- Sanitary facilities

MANUFACTURER

- 3A Composites

- Alape

- Armstrong

- Caparol

- Eternit

- FSB

- Gira

- Hagemeister

- JUNG

- Kaldewei

- Lamberts

- Leicht

- Solarlux

- Steininger Designers

- Stiebel Eltron

- Velux

- Warema

- Wilkhahn

-

Follow Us

Tumblr

New and existing Tumblr users can connect with uncube and share our visual diary.

»I hate vacations. If you can build buildings, why sit on the beach?«

Philip Johnson

Keyboard Shortcuts

- Supermenu

- Skip Articles

- Turn Pages

- Contents