-

A life extraordinary

By Irene Meissner

-

With his lifetime achievements, Frei Otto gave German architecture after 1945 an international relevance like no one else. Writer and curator Irene Meissner, co-author of a forthcoming book on Frei Otto, gives an introduction to the life, works and inspirations of this extraordinary architect.

Frei Otto, born in 1925, was the son of a stonemason and sculptor and belonged, by his own account, to a generation “shot into adulthood by the war”, who afterwards “wanted to get over the war, the megalomania, the cult of the Führer and of personality”. Many of his key ideas can be traced back to his formative experiences.

His unusual Christian name “Frei” (Free) was his mother’s invention. To be free was her philosophy in life, one she certainly passed on to her son. Frei Otto possessed a spirit that was free, critical and independent. As a teenager he was fascinated by gliders, but after secondary school, enrolled at the Technical University in Berlin to study architecture. However, with the Second World War, he was drafted into the German air force, and as a fighter pilot witnessed how buildings planned for the “new eternity” of the Third Reich disintegrated beneath the downpour of bombs. Later as a prisoner of war near Chartres, France from 1945 to 1947, he became camp architect, where, constrained by the scarcity of building materials, he taught himself the basics of simple lightweight construction.

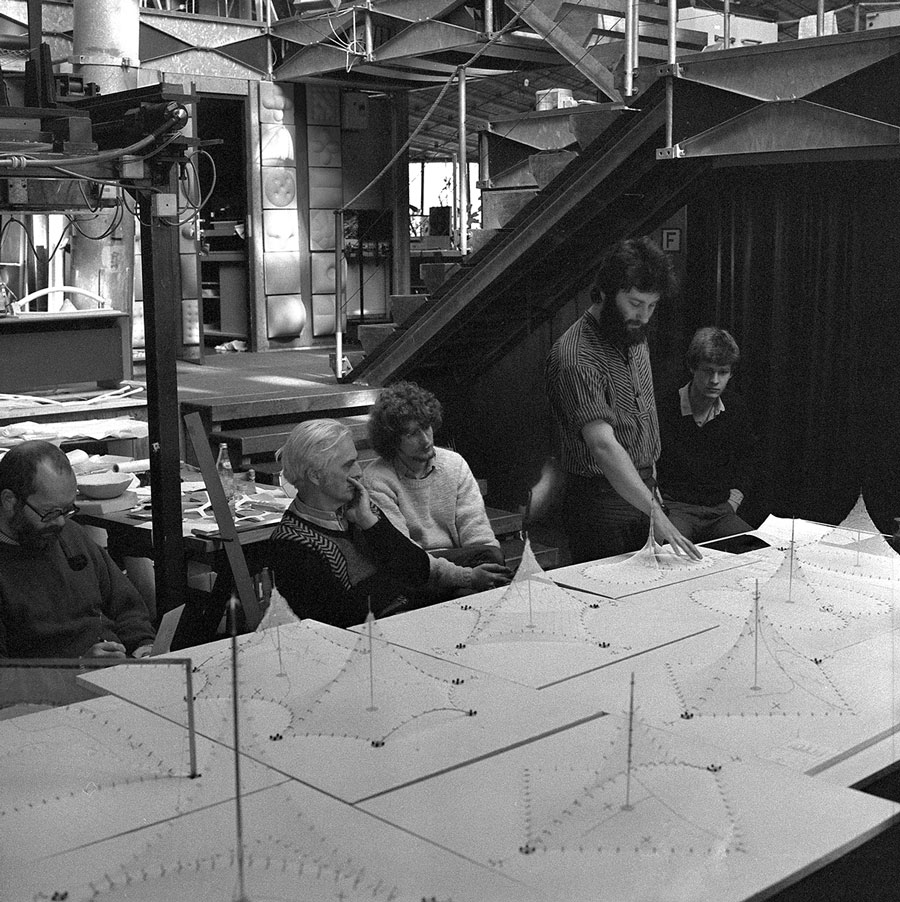

In 1947 Otto resumed his architecture studies in Berlin and in 1950 travelled to the United States as a fellow of the German National Academic Foundation. At the office of Fred Severud he saw the suspended roof construction for the Raleigh Arena in North Carolina by Matthew Nowicki, which was to become a key source of inspiration for his future creations. In 1954 he presented his own research in the field of tensile, cable net construction in his groundbreaking dissertation entitled: The Hanging Roof.Previous page: Otto shooting his model design concept for Berlin Olympic Stadium’s grandstand roof, 1970. (Photo: © Fritz Dressler, Worpswede)

-

Photo: © ILEK, Stuttgart

-

After the First World War, Bruno Taut countered a world gone awry by proposing his Alpine Architecture project – in which he proposed that new world harmony would be created by uniting nature, glass and crystal – similarly, Otto, after the Second World War, developed a vision for a people-oriented architecture in harmony with nature, deriving its form from the laws of nature itself. He experimented with materials that had not previously been considered as building materials, such as fabrics and air. Not only was Otto exploring uncharted territory, but he also offered a new architectural approach that diverged radically from the Nazi era. He countered sombre, massiveness, axiality and symmetry with lightweight, floating, asymmetrical forms that oriented themselves to the individual with agility and adaptability. “With lightness against brutality” and against the “architecture of killing” were a couple of expressions with which Otto succinctly summed up his driving concept.

1.

3.

2.

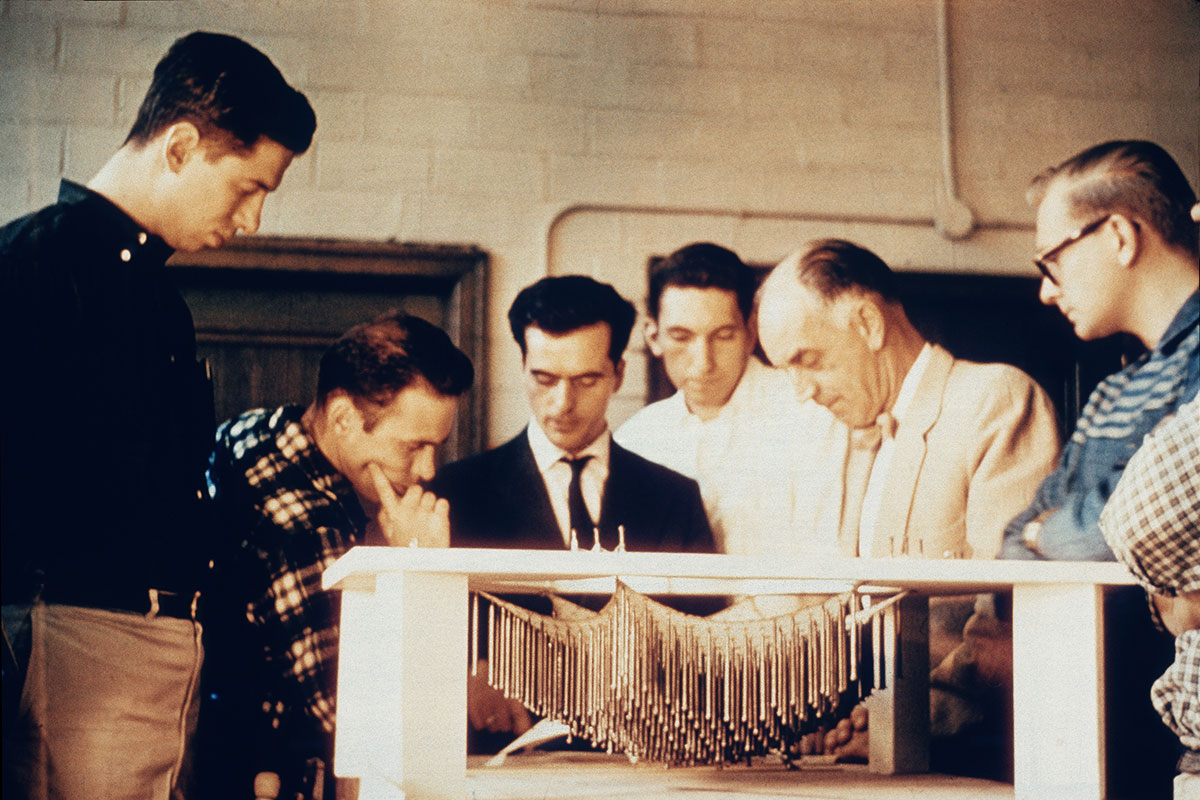

1. Otto leads a seminar on lightweight structures in 1958 at Washington University, St Louis, Missouri. (Photo: © ILEK, Stuttgart);

2. Otto busy testing new forms inside... & 3. ...outside. (Photos: Carsten Schröck) -

Otto in the garden of EL, Berlin, with a net model of his reworked construction plan for Behnisch & Partner’s Munich Olympic Park concept, 1968. (Photo: © Fritz Dressler, Worpswede)

-

Otto built his first tensile structures in 1955 together with the tent-maker Peter Stromeyer for the Federal Horticultural Exhibition in Kassel. Their music pavilion there was a four-point, saddle-shaped shade sail, with stability provided by a membrane spanned between two high and two low points. Its aesthetic quality was even lauded as an artwork at the first Documenta, which was running concurrently in Kassel. In the following years, Otto took membrane construction to new heights, elevating it to a recognised architectural form. Through his numerous wave-, dome-, pointed- and humpbacked-tent forms he explored the potential of this building technique, and in the process discovered that membranes could not be designed per se, but that their forms emerged within a given framework of parameters in a natural process of form-finding.

In 1958, as a visiting professor at Washington University in St. Louis, Otto discovered in the work of Richard Buckminster Fuller a fellow protagonist of lightweight, adaptable construction and a shared belief in its ability to improve the quality of life. Like Otto, Fuller was interested in achieving maximum efficiency with a minimum expenditure of materials and energy. While Otto derived his insights from biology – looking to the cell as nature’s smallest building block – Fuller was experimenting with octahedrons and tetrahedrons based on geometric chemical molecules, which he composed into structures like the geodesic dome, both aimed at creating better human living conditions. Otto pursued similar ideas and as early as 1953 drafted speculative plans for a town in Antarctica built beneath a cable net dome.

Otto conducted his early research in Berlin at the “Development Centre for Lightweight Construction” (EL), which he privately founded in 1958. In 1964, upon the recommendation of engineer Fritz Leonhardt, he was invited by the Technical University in Stuttgart to head their newly established “Institute for Lightweight Structures” (IL). An initial success of the Institute’s intensive research on cable net constructions was the competition submission Otto developed with Rolf Gutbrod for the German Pavilion at the 1967 World Expo in Montreal. The prototype they built in Stuttgart for this internationally celebrated construction, with its minimal surface area and a cable net spanning between high and low points, would later come to house Otto’s increasingly celebrated institute. The “tent” in Montreal served as inspiration for the architects Behnisch & Partner in their competition submission for the 1972 Olympic Games in Munich. The solution for the planned rooftop, delicately floating across the landscape, came from Frei Otto. He worked with a team of experts, including Fritz Leonhardt and Jörg Schlaich, to develop the cable net roofs, which still garner worldwide attention today. -

Following on from his development of membrane and cable net structures, Frei Otto turned his attention to arches, grid-shells and vaults. Notable was the Multihalle in Mannheim from 1974, a groundbreaking building that combined a form naturally evolved from its timber gridshell with immense flexibility. He also studied natural structures and the form-finding processes inherent in branches, pneumatic and large shell structures, and constructive technology’s origins in the shapes of nature became a running theme in the work of the IL. In 1960 Frei Otto met the biologist and anthropologist Johann-Gerhard Helmcke in Berlin, who introduced him to organic self-formation processes. After that, Otto was devoted to understanding natural processes and structures and applying their principles to load bearing architectural constructions. In 1984 he set up a special research project on “natural constructions” at the IL. The project resulted in a unique synergy as scientists from diverse fields shared and collaborated on theories, experiments and research. This fruitful form of cooperation yielded several inspirational symposia and publications, making Frei Otto’s Institute the most vibrant and creative research centre in Germany, with an international reach.

Otto presenting, listening, and talking at an outdoor seminar in 1968. (All photos: © ILEK, Stuttgart)

-

Irene Meissner is an architectural engineer, writer and curator at the Architekturmuseum der TU München. One of the contributors to the book Frei Otto, The Complete Works (2005), she is the author with Eberhard Möller of Frei Otto – forschen, bauen, inspirieren (Frei Otto – A life of research, construction and inspiration), which will be published by DETAIL, Munich in May 2015 and was originally planned as a tribute to Otto on his 90th birthday.

The book has a contribution by Georg Vrachliotis of saai – the Southwest German Archive for Architecture and Civil Engineering – to which in 2010 the State of Baden-Württemberg entrusted the archive of Frei Otto’s works after its acquisition.

irene-meissner.de

architekturmuseum.de

For Frei Otto, the role of the architect was as a mediator between people and their habitat, whose duty was the “preservation of the biotope”. His approach drew from the social approach of the Neues Bauen (New Building) movement from the Weimar Republic, which included Bruno Taut’s vision of the earth as a “good dwelling”. Long before the environmental movement and the establishment of “green” parties, he recognised and conducted fundamental research on the problems of our environment. At the height of post-war reconstruction in Germany, Otto called attention to misguided developments in architecture, such as the squandering of resources on purely profit-driven building. In a highly regarded speech he made in 1977 at the Schinkelfest in Berlin, he vehemently criticised his colleagues and demanded: “Stop building the way you build! It is unnatural!” He discussed alternative solutions at IL symposia on “natural building” and demonstrated his vision of an ecologically-based and participatory architecture with his eco-houses built for the 1987 International Building Exhibition in Berlin.

In the catalogue for the exhibition on Otto’s work, presented in 2005 at the Architecture Museum of the Technical University in Munich, Norman Foster aptly summed up his importance: “As much, then, as his extraordinary sequence of works altered the nature of architectural form in the twentieth century, his environmentalism, intelligence, and foresight have established the defining architectural mentality for the twenty-first. He is an inspiration.” I

Photographing the competition model for Berlin’s Olympic Stadium roof, 1970. (Photo: © Fritz Dressler, Worpswede)

-

Search

-

FIND PRODUCTS

PRODUCT GROUP

- Building Materials

- Building Panels

- Building technology

- Façade

- Fittings

- Heating, Cooling, Ventilation

- Interior

- Roof

- Sanitary facilities

MANUFACTURER

- 3A Composites

- Alape

- Armstrong

- Caparol

- Eternit

- FSB

- Gira

- Hagemeister

- JUNG

- Kaldewei

- Lamberts

- Leicht

- Solarlux

- Steininger Designers

- Stiebel Eltron

- Velux

- Warema

- Wilkhahn

-

Follow Us

Tumblr

New and existing Tumblr users can connect with uncube and share our visual diary.

»Form follows feminine.«

Oscar Niemeyer

Keyboard Shortcuts

- Supermenu

- Skip Articles

- Turn Pages

- Contents