-

Mies student and Otto disciple Conrad Roland

By Oliver Elser

-

Previous page: Conrad Roland’s 1964 sketch for an exhibition hall with floating platforms. This page: Roland’s “Giant Spacenet” put to the test in Peiting swimming pool, Bavaria, 1975;

Roland’s unbuilt Abu Dhabi stadium design, a collaboration with Jörn-Peter Schmidt-Thomsen, c.1977. (Drawing and all photos courtesy Conrad Roland).The 81-year-old architect Conrad Roland, famous for his Spacenet play structures, has lived in Hawaii for the past 27 years. But before that, his eventful life took him from his birthplace in Munich to Chicago, Berlin and Tahiti. Back in the 1950s, Roland studied at the Illinois Institute of Technology (IIT) in Chicago and then worked for Mies van der Rohe before moving to Berlin to work for a while with Frei Otto. He is perhaps the only architect equally at home in the contrasting worlds of Mies and Frei. Oliver Elser talked to him about his life’s journey.

-

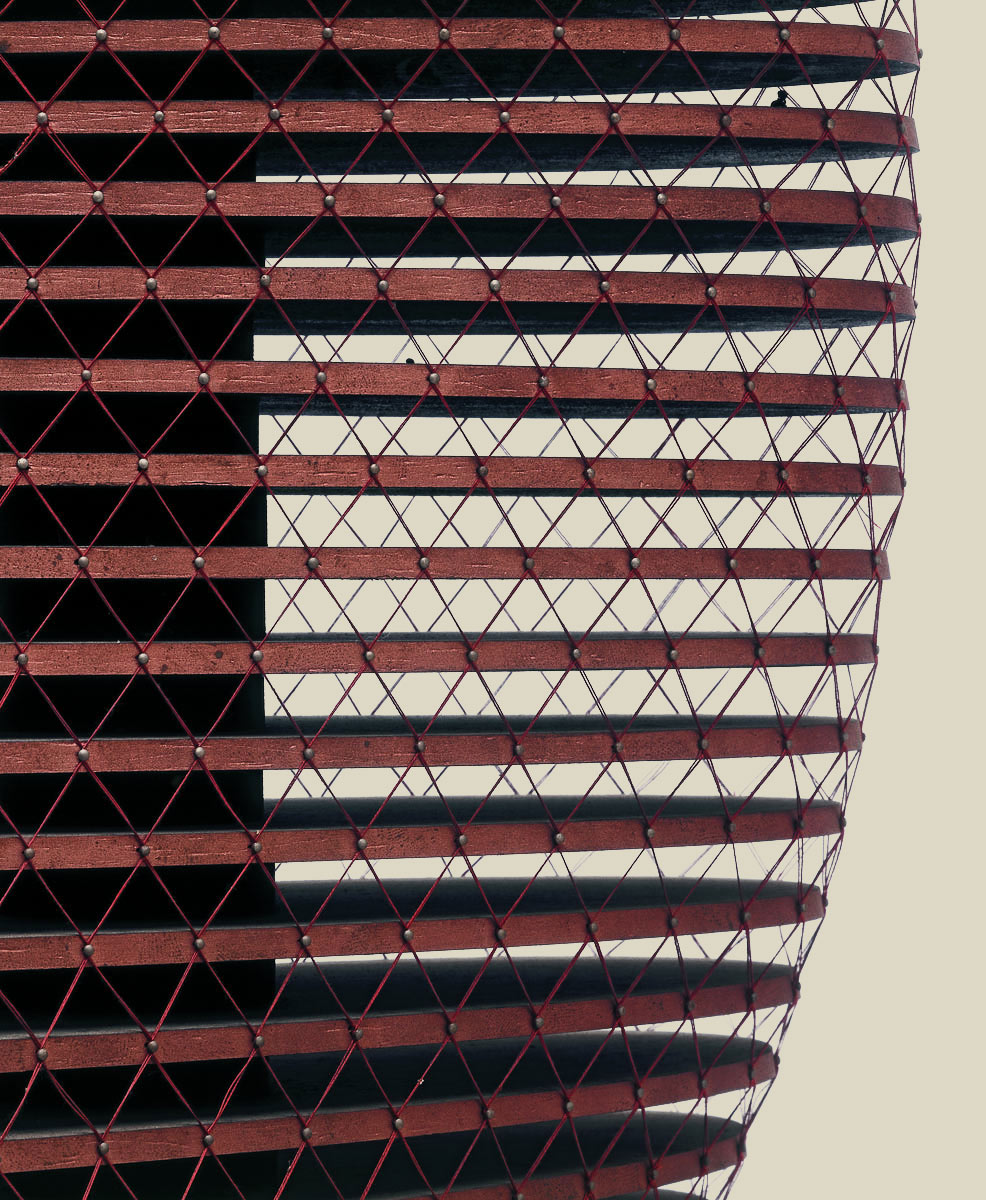

Otto wasn’t the only one to experiment with the idea of a tensile-structure stadium: a model of the Roland’s 1960s Abu Dhabi stadium project.

-

It is after midnight in Holualoa when the phone rings, but Conrad Roland is wide awake: “The night owl here!” he replies. Our conversation begins with me asking him how he got from the prestigious IIT in Chicago to the office of a, then unknown, architect in Berlin. “The path from Mies to Frei was very short”, he replies, “physically, only about 20 feet”.

It all started in the Institute’s famous Crown Hall, where Roland was a graduate student under professors (and former Bauhaus colleagues) Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Ludwig Hilberseimer, and Walter Peterhans. There he worked on his masters thesis between 1958 and 1959.

“Crown Hall is a large open space with only three closed-off spaces inside, called ‘cores’, which were used and abused for storage of old models and all kinds of bits and pieces”, explains Roland. “There I found a broken section of a space frame model made of toothpicks, a leftover from one of Konrad Wachsmann’s students. I became very curious and it inspired me to use a similar three-dimensional filigree lightweight structure for the wide-span roof of my thesis project for ‘An Arts Centre’ in 1959”. At the time, Roland was not yet aware of the Mero roofs built at the Interbau exhibition in Berlin in 1957, which bore membrane structures designed by the young Frei Otto. “Another trip to the Crown Hall core, perhaps looking for some model building material, resulted in a discovery that two years later changed the course of my life as a young architect”. Here Roland found one of Frei Otto’s IL bulletins, dating from 1958, entitled Mitteilung der Entwicklungsstätte für den Leichtbau Nr. 3, Eingangsbogen BUGA Köln, 1957 (Publication from the Development Centre for Lightweight Construction No. 3, Entrance Arch, BUGA [Federal Horticultural Exhibition], Cologne 1957) and was “fascinated by the totally new structure, form, and most dynamic character” of the lightweight fabric membrane it documented. After working in Mies van der Rohe’s office from 1958-61, Roland returned to Germany and headed straight to Berlin. “Needless to say, one of my first excursions there was a long bus ride to Zehlendorf to see Frei Otto at his Entwicklungsstätte für den Leichtbau (Development Centre for Lightweight Construction). It was a most inspiring meeting… with a genius! He handed me a folder with hundreds of sketches for suspended buildings using mostly cable construction. He said: ‘If you are interested, take it with you and make something of it. I am too busy with other things.’” Roland took the folder, wrote some explanatory texts to go with the material and added a few sketches of his own before publishing it as Mitteilung Nr. 8, Mehrgeschossige zugbeanspruchte Konstruktionen (Publication No. 8, Multilevel Tensile Constructions) in 1962. -

That marked the beginning of Conrad Roland’s close relationship with Frei Otto and tensile structures. However, a brief stint in Frei Otto’s office working on actual projects did not turn out too well: “because I inevitably turned out to be a ‘Mies perfectionist’, which collided at certain points with Otto’s somewhat less-than-perfect architectural detailing. We parted in peace after a few weeks, but with my enthusiasm unbroken.” In 1964 Roland began working on the first book to document the already amazing body of innovative work by Otto called: Frei Otto – Spannweiten (Frei Otto – Tension Structures) which he modestly called simply a “report”.

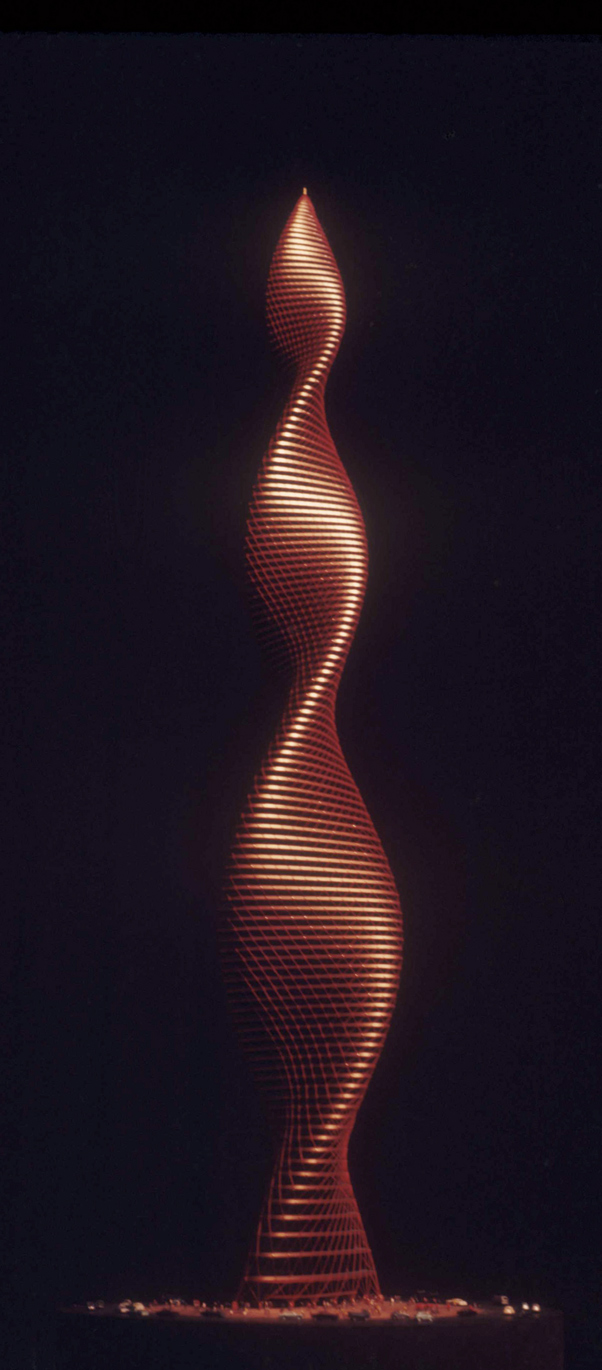

Parallel to his work on the Frei Otto book, he developed countless designs for his own tensile structures. Several skyscrapers, a community centre, apartment buildings and a studio tower. They are poetic, playful, and revolutionary, all at the same time. The most fantastic and consistently logical design he created is his “Spiral Skyscraper”, a 120-storey suspended building reaching 440 metres high, which is one of the most original, visionary skyscraper designs of the 20th century. But it was never built. In 1970, Conrad Roland began designing so-called “Play Spacenets” – three-dimensional tensile climbing nets made of rope and suspended from masts – that became a global bestseller. His company Corocord went on to produce thousands of Spacenets for playgrounds and schoolyards and today exports its products to more than 50 countries.But after 15 years, Roland says, he got bored. So he sold the company to a young Greek architect and left Germany. First for Hawaii, followed by Tahiti, and then back to Hawaii. It is here that he finally decided to build his own house with a four-mast canopy roof design that he’d carried around with him for years. But somehow the house never happened. “It’s the tragicomedy of my life,” he tells me.

This 120-storey, 440 metre high “Spiral Skyscraper” was proposed by Conrad Roland in 1964.

-

Oliver Elser is an architecture critic and a curator at the German Architecture Museum (DAM) in Frankfurt-am-Main, Germany.

On the plot of land that he originally purchased for building his house, 300 metres above sea level with stunning views over the Pacific, he is now planting bananas and citrus fruits instead. And he marvels about how often spiral skyscrapers have been popping up on the internet during the last few years. But unlike the formal madness of the twisted creations designed for Malmö, Dubai or Toronto, the form of Roland’s design developed purely out of its construction. He quotes his teacher Mies: “We make architecture with the structure alone.” It’s a sentence that could have been uttered by Frei Otto as well. I

Roland’s proposal for a giant cubic space-frame in Berlin‚ filled with residential cells, 1967.

-

Search

-

FIND PRODUCTS

PRODUCT GROUP

- Building Materials

- Building Panels

- Building technology

- Façade

- Fittings

- Heating, Cooling, Ventilation

- Interior

- Roof

- Sanitary facilities

MANUFACTURER

- 3A Composites

- Alape

- Armstrong

- Caparol

- Eternit

- FSB

- Gira

- Hagemeister

- JUNG

- Kaldewei

- Lamberts

- Leicht

- Solarlux

- Steininger Designers

- Stiebel Eltron

- Velux

- Warema

- Wilkhahn

-

Follow Us

Tumblr

New and existing Tumblr users can connect with uncube and share our visual diary.

»What the map cuts up, the story cuts across.«

Michel de Certeau: Spatial Stories

Keyboard Shortcuts

- Supermenu

- Skip Articles

- Turn Pages

- Contents