-

Enduring

ConsensusFreetown Christiania at forty-three

By Malcolm Miles

-

So many communes of the 1960s and 70s were children of their time and very few endured beyond a decade. But Denmark’s famous Freetown Christiania turns 43 this year. Cultural theorist Malcolm Miles believes the longevity of this robust community owes as much to its protracted system of self-government as it does to eco-friendly attitudes and the relatively tolerant reputation of its host country.

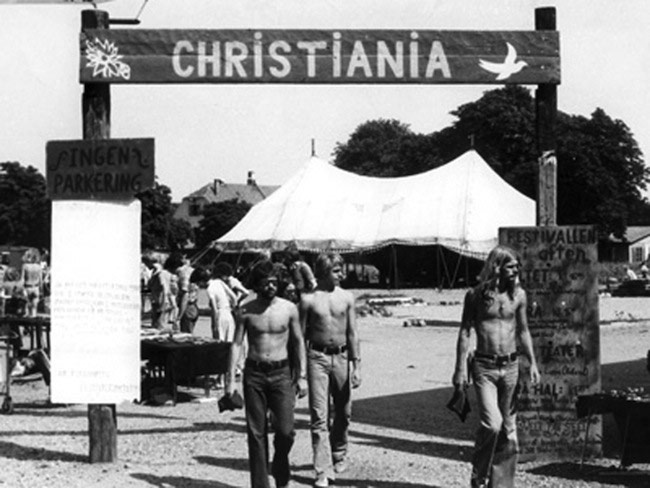

In 1967, the Danish military moved out of a 34-hectare site that had served as a barracks in a central enclave of Copenhagen since the seventeenth century. The area fell into a dilapidated state until, in September 1971, it was declared “free” by members of local squatter movements, with Freetown Christiania founded the following year.

Today, tourist websites promote the opportunity to visit Christiania “like an insider”, with reviews ranging from “So cool! What a way to live!” to “This is one of those places you either love or hate… I hated it”. The community is one of Copenhagen’s biggest tourist attractions. It is car-free (although some residents have shared cars parked nearby), has several cafés and shops, and contains footpaths through woodlands and reed beds offering a quiet escape from the city. Although a right-wing government tried to reassert control over the site in 2004, aiming to redevelop it for condominiums – it is the kind of waterfront site from which developers make fortunes – Freetown has survived. It is still a commune, and one of Europe’s largest alternative settlements with a sustainable community of 850 people, despite failing to resist the government’s extension of its authority over the site in a series of court actions up to 2011.

Obviously there is more to Freetown’s survival than merely tourism; images of police clearing women and children from self-built houses in an idyllic setting once and for all would have done no favours to Denmark’s liberal image and the city’s lucrative cultural tourism trade. But that only explains why it has not been cleared, not why it remains a viable community, an alternative society within the territory of the old regime.

-

This is down to two other factors: Freetown’s social (rather than built) architectures, and its fusion of 1970s free living with today’s concern for more sustainable, greener forms of dwelling.

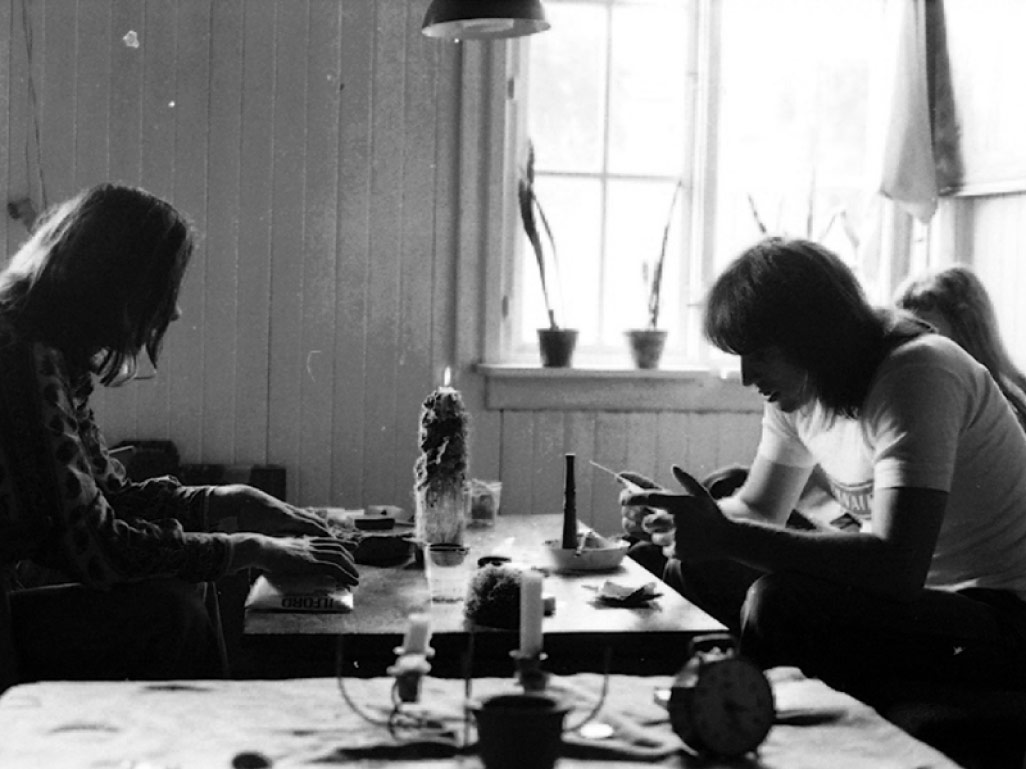

Like many intentional communities and eco-villages founded since the 1970s, Christiania employs consensus decision-making, not majority-voting (which is regarded as divisive and impositional). The process can be slow, but it generally creates social coherence by enabling everyone, on a basis of equality, to voice their feelings about everyone else. What is being discussed is less important than the act of discussion as a safety valve of vocal expression in proximity to others.

Whilst Freetown Christiania is seen by the Copenhagen city authorities as a single entity, it is actually a collective of many groups and individuals who have their own ideas as to its vision and purpose. For some members, retaining free use of soft drugs is a key, almost ideological issue; for others, negotiations over Christiania’s relations with the city are more like a planning process to be approached pragmatically. Therefore, despite three decades of more or less acceptable co-existence, when faced with threats from both city and state authorities to normalise governance and economic basis in the 2000s, the community’s internal meetings were large and at times fraught.

According to the government’s victory in the Supreme Court in 2011, Freetown was invited either to transform itself into a less alternative community, or to buy the site it occupies. The community’s first response was to close Freetown to visitors, thereby diminishing Copenhagen’s critical mass of attractions. This was, in effect, to go on strike. Behind the barriers, meetings moved slowly and at times painfully towards a plan, which involved the eventual purchase of the site for 125 million kroner (16.8 million euros), with significant deductions for renovation of services and repairs to listed buildings.

The principle of consensus has at times been a messy process, but has still proven to be vital research-and-development work for a new society evolving and enacting its own set of values. This is necessarily contingent on external conditions, and residents of Christiania pay rent and collectively contribute to the cost of services provided within the city’s infrastructure. In one way this is a normalisation; in another way, however, it is a negotiation to preserve what matters most: autonomy within the boundaries Freetown.

-

The residents of Copenhagen’s famous enclave have endured various threats to its sovereignty during the past four decades, but through the principle of consensus, they have worked to secure its future. (All photos courtesy christiania.org with the exception of resident meeting image, Nils Vest)

-

Malcolm Miles is Professor of Cultural Theory in the Architecture School at the University of Plymouth. He is author of Urban Utopias: The built and social architectures of alternative settlements (2008); Herbert Marcuse: An aesthetics of liberation (2011) and Eco-aesthetics: Art, literature and architecture in a period of climate change (2014). His next book is Limits to Culture (2015), a critical retrospect on the cultural turn in urbanism since the 1980s.

malcolmmiles.org.uk

Recently, a series of workshops, conducted according to the rule of consensus, produced a new plan for Christiania; with it, the town’s existence has now been officially recognised by the city. The new plan has a greater emphasis on ecology, which has always been part of the Freetown ideology. But while a few radical thinkers in the 1970s, such as Rudolf Bahro and Herbert Marcuse, saw environmental destruction as the flip-side of military destruction during the Vietnam War, it is only now, with the effects of climate change being felt, that the links between military, industrial and security interests under neoliberalism have gained prominence.

Whereas much discussion about sustainable cities remains technical – designing green skyscrapers or devising new energy reductions – it tends to ignore the social sustainability aspect, which is an equally vital consideration for a greener future. Christiania is now looking to increase food production on site, extend its car-share scheme, recycle waste from the whole of Denmark, and continue to operate through consensus decision-making. There will be more long and difficult meetings, no doubt. Yet that is how a radically new society replaces the hierarchies and hegemonies of the dominant society through equality and direct democracy. The social architecture of consensus is not an add-on, but is what has enabled Freetown to remain free. I

-

Search

-

FIND PRODUCTS

PRODUCT GROUP

- Building Materials

- Building Panels

- Building technology

- Façade

- Fittings

- Heating, Cooling, Ventilation

- Interior

- Roof

- Sanitary facilities

MANUFACTURER

- 3A Composites

- Alape

- Armstrong

- Caparol

- Eternit

- FSB

- Gira

- Hagemeister

- JUNG

- Kaldewei

- Lamberts

- Leicht

- Solarlux

- Steininger Designers

- Stiebel Eltron

- Velux

- Warema

- Wilkhahn

-

Follow Us

Tumblr

New and existing Tumblr users can connect with uncube and share our visual diary.

»Less is a bore.«

Robert Venturi

Keyboard Shortcuts

- Supermenu

- Skip Articles

- Turn Pages

- Contents