-

Robots that were made to be loved

By Claire L. Evans

-

Do tech corporations have moral responsibilities towards customers who develop emotional relationships with their products? Or should they just be allowed to take on a life of their own? uncube’s science and culture correspondent Claire Evans reports on the commercially obsolete canimorphic AIBO robots whose owners are struggling to keep them “alive”.

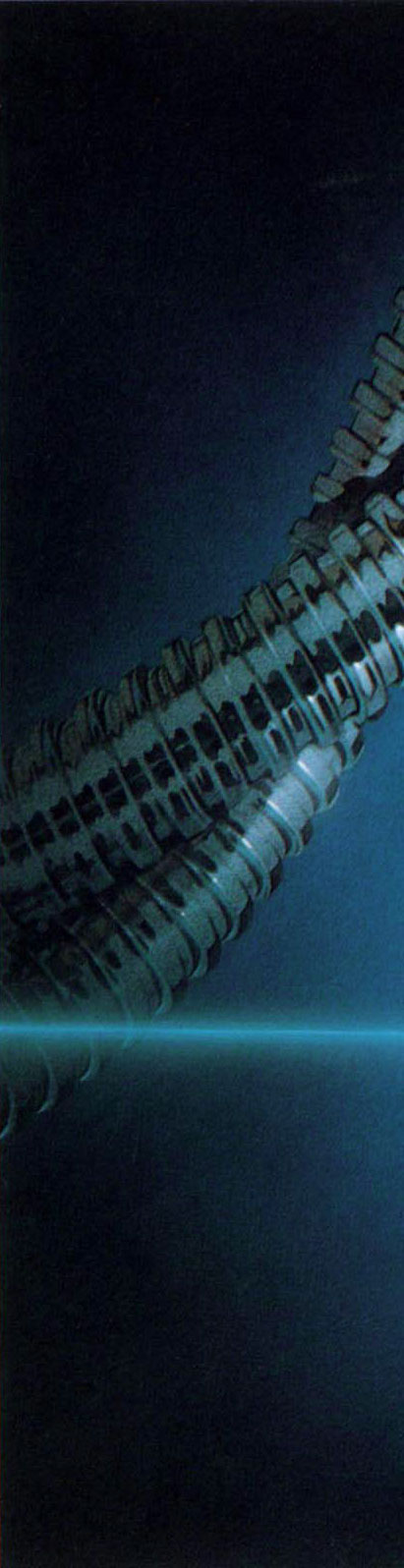

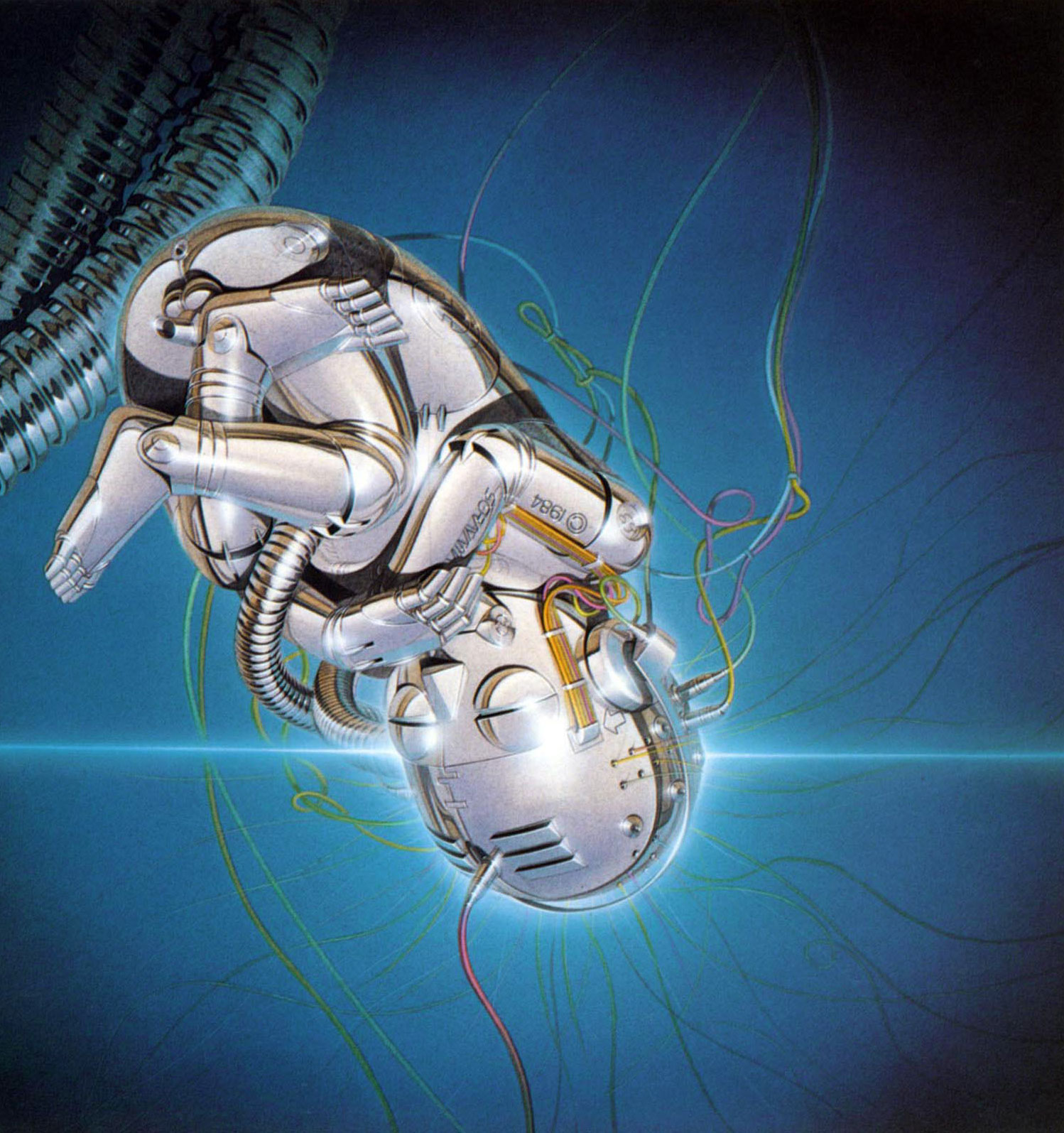

Previous page: Image © Sorayama/Artspace Company Y/ Uptight, 2015. This page: Aibo Entertainment Robot (ERS-110), Hajime Sorayama, Sony Corporation, company design. (Photo © the Museum of Modern Art)

-

Robots work. That’s what they do. From the first usage of the word – in the Polish writer Karel Capek’s play Rossum’s Universal Robots, in which “robots” are biological drones engineered to serve human masters – labour has been central to the robot’s identity. Both in the collective fantasy of science fiction and in the factories of the 21st century, robots work: building cars, assembling consumer electronics, lifting loads and even checking-in hotel guests.

That is, except for AIBO.

A robot pet designed and marketed for domestic use by the Sony Corporation, AIBO was never meant to do anything. Despite being the most sophisticated product ever offered in the consumer robot marketplace, it is not an appliance, it is not designed to bear any burden beyond the emotional attachment of its owner. Or as Takeshi Yazawa, vice president and general manager of Sony Entertainment Robot America, once explained: “AIBO loves you, you love AIBO, and that’s it”.

AIBO – which means “companion” in Japanese, but is also a quasi-acronym for Artificial Intelligence Robot – is a canimorphic robot. It wags its tail, cocks its head, and sits on its hindquarters when instructed, an eager puppy moulded in chrome-tinted plastic. But it’s more than a dog, of course. AIBO learns, expresses anthropomorphic emotional states, and communicates through auditory tone combinations and eye lamp patterns. To the inexpressible joy of thousands of AIBO owners, still maintaining their pets despite the fact that Sony discontinued the AIBO in 2005 and completely stopped repairing AIBOs in 2014, the robot dogs can even dance, sometimes synchronously in groups. Videos of this phenomenon are strangely moving: a chorus of willing companions, their metallic paws clicking on hardwood in precise concert.The original AIBO phenotype was designed by Hajime Sorayama, a Japanese artist best known for his erotic airbrush paintings of female androids, flat images rendering the curves of women in glassy, metallic lustre. His robot design, now in the permanent collections of the Smithsonian Institution and MoMA, is a fascinating instance of life imitating art: Sorayama made a career illustrating sensual gynoid women in the throes of pleasure, lounging, riding bicycles, handling consumer goods, completely untethered from labour and AIBO, the only robot he ever participated in building, only knows play.

»In Japan,

-

emotional attachment to robots is deeply ingrained.«

Later iterations of AIBO were designed by Shoji Kawamori, better known as an anime creator, and the manga writer and artist Katsura Hoshino. AIBO was exceptional for many reasons: although it functioned, it didn’t work and artists – not just engineers and industrial designers – were instrumental in every phase of its design.

The result was a robot that immediately became an emotional centre of gravity. Designed with an element of fantasy and a respect for the grace of a personal robot’s objecthood, AIBO may well have been the first consumer robot to be loved. It could never disappoint its masters because it had no job at which to fail.

In Japan, emotional attachment to robots is deeply ingrained. Shinto, Japan’s indigenous religion, is an animist faith, its adherents believe that non-human entities, such as animals, plants and robots possess a spiritual essence. AIBO is no exception. As a recent New York Times documentary piece profiled with great empathy, AIBO owners all over Japan grieve for their pets, which – now that Sony has ceased all repairs and customer support in a bid to improve profitability – are starting to break down irreparably.Image © Sorayama/Artspace Company Y/ Uptight, 2015

-

»What if all robotics development was rooted, like this, in deep attachment?«

Image © Sorayama/Artspace Company Y/ Uptight, 2015

-

Even if Sony still made new models, a lost AIBO could never be replaced since each dog’s personality is moulded by a life spent learning from its owner. Such is the attachment that develops, it is not uncommon for AIBO owners to hold funerals for dogs departed to the great charging cradle in the sky.

The AIBO mind is mutable. When Sony still manufactured them, between 1999 and 2005, it sold companion software called AIBOware to run on the synthetic pet. The Life AIBOware emulated the lifespan of a real animal, allowing owners to raise the robot from puppyhood to mature development. In later years, third-party developers began to create open-source software packages for AIBO, a culture Sony initially attempted to curtail, invoking copyright issues, before eventually releasing an SDK for non-commercial use. Using the high-level scripting language R-Code, programmers have created a litany of AIBO personalities, many of which are available for free on the Robot App Store. DogsLife, for example, expands the basic AIBO personality with hundreds of additional performances and “fun doggish whims” and Disco AIBO allows AIBOs to dance.

Active forums all over the web are testament to the culture of AIBO hacking, which remains small but robust; the dogs are malleable and pliant, their machine minds abandoned by their corporate makers, waiting only to be moulded further. Robotics students and hobbyist engineers have embraced AIBO as an inexpensive research and teaching tool. And even in non-technical circles, a sort of folk culture has sprung up around these machines; their owners clothe them, pose them, take them on holidays, and swap software personalities and advice online. Despite being “obsolete”, AIBOs are arguably more capable and more intelligent than ever before, simply by virtue of being loved.

It’s significant enough a phenomenon to warrant the question: what if all robotics development was rooted, like this, in deep attachment? What if, instead of developing intelligent machines for work – in industry, for war, or explicitly to displace human labourers – we developed intelligent machines out of love? Never mind what it can do. You love AIBO, and that’s it – until one day, AIBO, or something like it, loves you back. I

-

Search

-

FIND PRODUCTS

PRODUCT GROUP

- Building Materials

- Building Panels

- Building technology

- Façade

- Fittings

- Heating, Cooling, Ventilation

- Interior

- Roof

- Sanitary facilities

MANUFACTURER

- 3A Composites

- Alape

- Armstrong

- Caparol

- Eternit

- FSB

- Gira

- Hagemeister

- JUNG

- Kaldewei

- Lamberts

- Leicht

- Solarlux

- Steininger Designers

- Stiebel Eltron

- Velux

- Warema

- Wilkhahn

-

Follow Us

Tumblr

New and existing Tumblr users can connect with uncube and share our visual diary.

»Intelligence starts with improvisation.«

Yona Friedman

Keyboard Shortcuts

- Supermenu

- Skip Articles

- Turn Pages

- Contents