-

The Aesthetics of Zaha Hadid

By Jonathan Bell

-

Zaha Hadid Architects is now a practice of over 400 employees renowned for its sophisticated computer-based design, but its founder has always drafted by hand. Architecture critic Jonathan Bell looks at Hadid’s exceptional sense of aesthetic form that has made her an artist among architects.

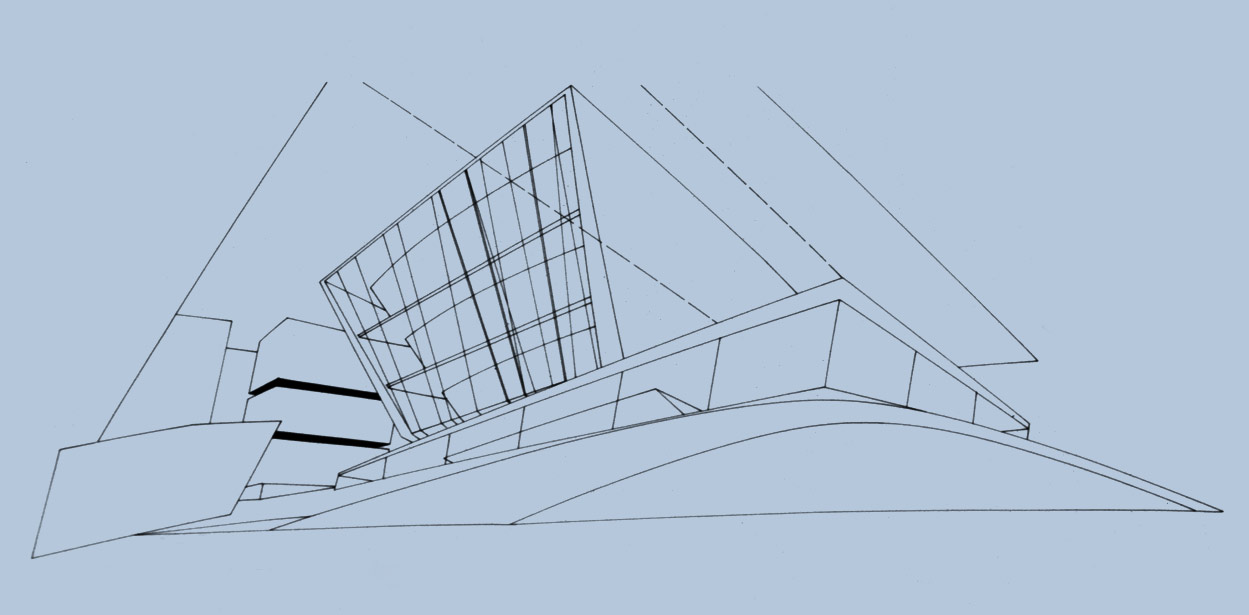

Previous Page: Site plan drawing for the Peak Leisure Club (unbuilt), 1982-83, Hong Kong. This page: Vitra Fire Station, 1990-93, Weil am Rhein.(All images courtesy Zaha Hadid Architects)

-

The aesthetics of the avant-garde in architecture is what has always drawn in the eye. It's what engages with the public and the city that surrounds it. Reams of theory and terabytes of data might underpin cutting edge architectural form, but the factor that shapes the way we perceive these buildings is pure and simple: aesthetic form.

Zaha Hadid is a very aesthetic architect. That is to say that the Iraqi-born British Dame of high design is an architect who can be defined almost entirely by form, despite the solid layers of theory and even more solid technological underpinnings that shape every building and product that comes out of her studio. From Hadid's earliest works, produced while a student at the Architectural Association in London, her formal adventurousness has been pushed to the fore. Naturally, in the days before digital and 3D printing, the best form of expression was the drawing, and Hadid's drafting stood out as exceptional, particularly the large-scale canvases she produced, depicting her buildings as facetted, deconstructed forms scattered across skewed landscapes.

These works brought her work to wider attention, most notably with a competition-winning entry for The Peak restaurant in Hong Kong in 1983, a work that still appears contemporary to our pixel-saturated eyes by dint of the extreme geometry of its forms and the boldness of the presentation; a cascade that slices across a deliberately distorted Hong Kong cityscape. -

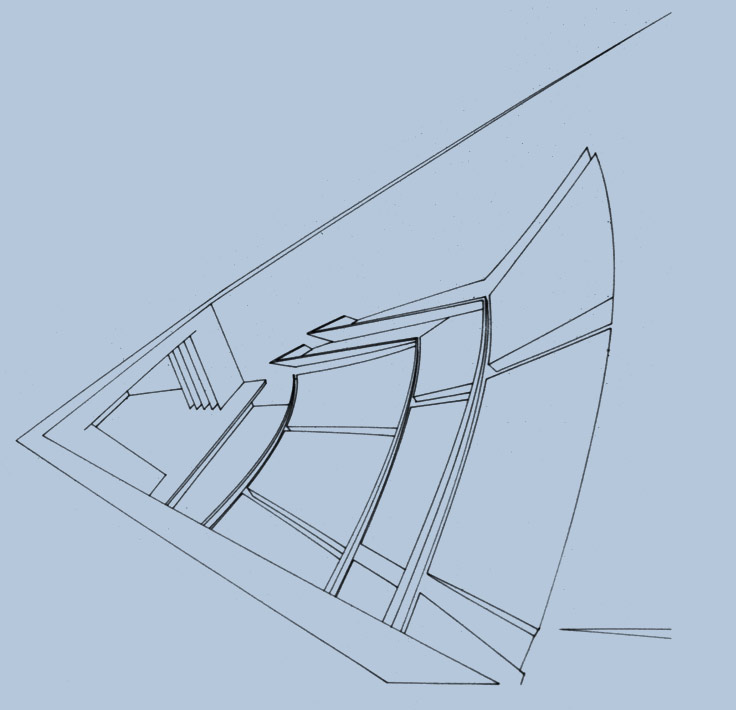

Cardiff Bay Opera House competition entry, 1994-96, UK.

From the outset, Hadid's presentation transcended that of her peers. For the architectural press of the pre-digital era, this suggested it could be placed in only a few stylistic pigeon holes – the “paper architecture” of the perennially unbuilt (and possibly even unbuildable) or, more intellectually, the Deconstructivist School pioneered by Peter Eisenman and Daniel Libeskind. In hindsight, “Decon” existed at the juncture between post-modernism and the digital era. Although it was hard to define yet easy to recognise, it was Hadid who ultimately took the genre from the page and into built reality. With the Vitra Fire Station in Weil-am Rhein (1993), those exaggerated perspectives and vanishing points were suddenly made real, instantly crumbling the modernist relationship between form and function. The following year, the studio's winning entry in the Cardiff Bay Opera House competition seemed to consolidate Hadid's ascendance, but it was a false dawn and the project collapsed in acrimony. For a few years, Hadid was in the wilderness.

Throughout this period the studio's aesthetic sense evolved in parallel with emerging technology. Whereas Hadid's earlier works presented a physical, analogue interpretation of what might otherwise be considered impossible, the practice's emphasis on research and experimentation has reaped dividends in the way it translates organic form into architecture. In particular, this has manifested as a commitment to parametricism, an architecture generated from the brief, the site, the programme and the materials. In short, a parametric building is one that uses the intrinsic complexity of the many parameters that make up a building to express them in physical form.

More problematic, perhaps, is the way in which the practitioners of parametricism decry its association with traditional aesthetics. Patrik Schumacher, Hadid's creative partner, wrote a dense two-volume, 1,300-plus-page thesis, The Autopoiesis of Architecture, in which aesthetics get relatively short shrift, buried beneath near-impenetrable layers of theory. Yet Hadid has always presented herself as an artist, from the oil paintings and prints she undertook as a student to the more explicitly sculptural pieces she has created throughout her career as an architect. Parametricism seems to deny artistic intent, or at the very least obscures it. The sensuality of this architecture – for curves, kinks, bends and scoops are always in some respect sensual – is thus overshadowed by a misplaced determinism, almost as if its authors are afraid of engaging with the concept of beauty at all. -

Jonathan Bell is an editor, copywriter and design consultant. He has written about art, design, architecture and automobiles for many leading titles, including Wallpaper* magazine. His books include The 21st Century House (pub. Laurence King), Penthouse Living (pub. Wiley-Academy) and The New Modern House (pub. Laurence King).

Parametricism has its imitators, for as an approach it is just as total and all-consuming as the High Modernism of the 20s and 30s. Yet even slavish imitation falls somewhat short. Perhaps that's what Hadid's work is so good at reminding us, as her most successful buildings graduate from page to site with a satisfying robustness thanks to the physicality of concrete, steel and glass enhancing the twist and thrust of their forms. Linear, multi-functional spaces like the Evelyn Grace Academy school (2010) in south London, the jarring angles of the Eli and Edythe Broad Art Museum (2012) in East Lansing and the rippling facades of the CityLife Milano apartments (2014) in Italy all fulfil the promise of their plans. Regardless of technology, ideology or methodology, there is a fine sculptural mind at work.

Cardiff Bay Opera House drawings.

-

Search

-

FIND PRODUCTS

PRODUCT GROUP

- Building Materials

- Building Panels

- Building technology

- Façade

- Fittings

- Heating, Cooling, Ventilation

- Interior

- Roof

- Sanitary facilities

MANUFACTURER

- 3A Composites

- Alape

- Armstrong

- Caparol

- Eternit

- FSB

- Gira

- Hagemeister

- JUNG

- Kaldewei

- Lamberts

- Leicht

- Solarlux

- Steininger Designers

- Stiebel Eltron

- Velux

- Warema

- Wilkhahn

-

Follow Us

Tumblr

New and existing Tumblr users can connect with uncube and share our visual diary.

»Form follows feminine.«

Oscar Niemeyer

Keyboard Shortcuts

- Supermenu

- Skip Articles

- Turn Pages

- Contents