-

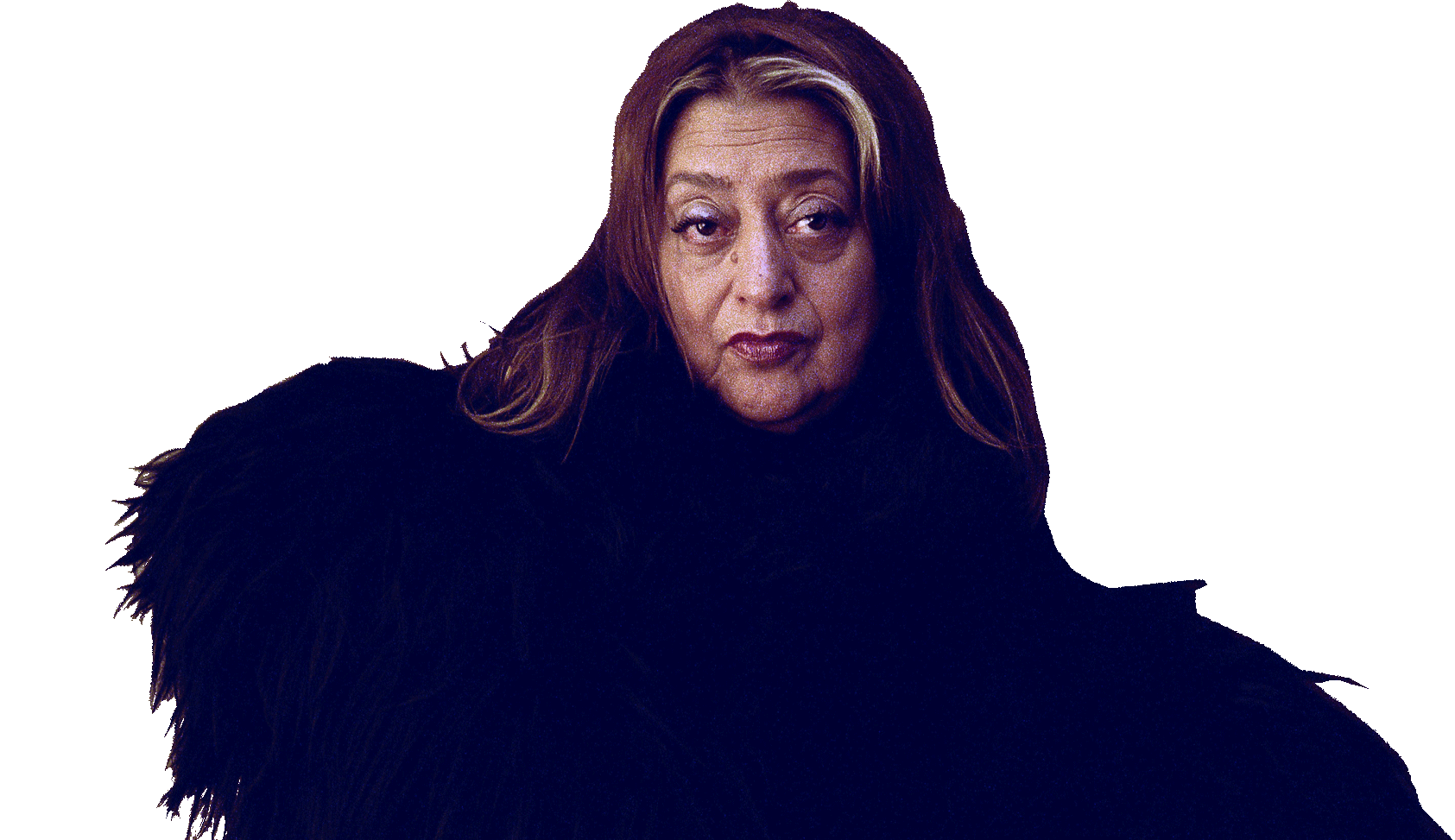

An Interview with the architect Zaha Hadid

by Sophie Lovell

-

aiting for Zaha is what happens to many that come into her orbit. She is after all an international figure heading a global concern operating dozens of projects worldwide. But as much as she is a leading starchitect she is also someone that polarises opinion like no other – and far beyond the realm of architecture. Why is that actually? In seeking to find out, uncube’s Sophie Lovell found patience paid off and encountered a reflective architect deeply involved in her work in all its facets.

Photos: Gautier Deblonde

-

All high-profile architects experience criticism at some time or other, but do you feel you have had more than your fair share? Do you feel you are sometimes misunderstood?

I’m a woman. I’m an Arab. I’m an architect. Biology and geography define the first two; the third has taken forty years of hard work. But hard work is not always enough. For a large part of those forty years, some of the biggest difficulties that I faced were brought about not by my work, but by my existence as a woman, or as an Arab, or indeed, as an ‘Arab Woman’. Ignorance and injustices, large or small, blatant or subtle, deliberate or – and perhaps worse – casual, not even recognised by their perpetrators.

I’m Iraqi; I live in London; I don’t really have a particular place - and can say from my personal experience, it is actually very liberating. Perhaps it was my flamboyance rather than being a woman that was the reason I didn’t fully fit into the culture at hand. I think, on one hand, it’s made me much tougher and more precise – and maybe this is reflected in my architecture.

Looking at your work, the diligence you apply in preparation by hand, in terms of sketches, drawings or paintings for each new project has been particularly noticeable. Do you have a routine or a regular path that you follow when approaching each new project concept?

Painting formed a critical part of my early career as the design tool that allowed us the intense experimentation in both form and movement - leading to the development of a new language for architecture. The painting was always a critique of what was currently available to us at the time as designers – as 3D design software didn’t exist. There has been a complete shift in the last, say, thirty years - to now doing some projects only on the computer. -

My paintings really evolved 30 years ago because I thought the architectural drawings required a much greater degree of distortion and fragmentation to assist our research - but eventually it affected the work of course. I’m not a painter - I have to make that quite clear.

I can paint - but I’m not a painter - as the paintings we created were always part of the research for our architectural projects. The paintings I’ve done are very important to me and if I did them again I’d do them in a very different kind of way, but they were very important at the time.

In the early days of our office, the method we used to construct a drawing or painting or model led to new discoveries. We sometimes did not know what the research would lead to – but we knew there would be something, and that all the experiments had to lead to perfecting the project. And these are the journeys that I think are very exciting, as they are not predictable.

The design processes in your projects over the years could be seen to have shifted from extremely warm, visceral, hands-on skills to a colder, machine-calculated and drawn, hands-off discipline. Would you agree? How does one maintain the warmth and vivacity in parametric design?

It is a different kind of operational psychology today.Previously, in an architect’s office, you’d have each individual do almost everything: make a model, design, answer the phone or make a slide presentation. Now, you have people who specialise in all the different aspects of the design and construction process, so we’ve worked hard to establish a collective research culture in our office where many talents can feed off each other’s ideas and experience.

The developments that computing has brought to architecture are incredible, and as such, the work is able to handle the much greater complexity and flexibility that clients require today. Computing has enabled an overall intensification of relationships - both internally within the buildings as well externally with the context.

I am, however, concerned that no one today really knows how to draw a plan. It took me 20 years to convince people to do everything in 3D, with an army of people trying to draw the most difficult perspectives, and now everyone works in 3D on the computer – but they think a plan is a horizontal section – it’s not. The plan really needs organisation via a diagram. -

You had an exhibition entitled “Form in Motion” in the US in 2012. Can you explain how important motion is to you in your work and how it differs, say, from the futurist notion of the representation of “speed”.

I’ve always been interested in how our movement through space affects architecture. As in the frames of a film: not seeing the world from one particular angle, but having a more complex view. We view the world from so many perspectives – never from one single viewpoint – our perception is never fixed. This movement through space is very critical in all buildings – which also impacts our perception of time and the relationships we establish with our built environment. It differs from the pure perception of speed.

For example, in our Kartal masterplan design for Istanbul, located in a large derelict industrial area to the southeast of the city on the Marmara coast, we established a fluid grid which builds up over time.Sections of the grid develop as an entire plot or only at the intersections; it is fluid in that it changes in time, programme and space. This gradation allows a process of ‘incomplete composition’, where a project grows organically over time, but looks and feels complete at any given point in its evolution.

You are mostly famed for your stand-alone cultural projects but more recently I notice, there are housing projects as well, such as the new development in Milan. What in your view is the extent of responsibility for an architect in terms of where their building ends and the surrounding urban, rural or social fabric begins?

Architecture can carry within it an inherent sense of vitality and optimism; the ability to connect communities and build their futures. Ecological sustainability and social disparity are the defining challenges of our generation, and an architecture of inclusivity offers solutions to these key challenges. -

As an architect, your client is no longer a single person or type of person, your client is everyone. All buildings should have a civic component. Even a commercial high-rise building should offer a civic programme – public spaces in which people can connect with each other and use as their own. Developers in both the public and private sectors must invest in these public spaces. They unite the city and tie the urban fabric together.

What else needs to change?

There has been a move in many of the world’s cities over the past years towards walled, private spaces. As architects, we must react to this. Over many centuries, architects have been trying to liberate the city, to open it up, to make our cities more porous and accessible. Building these gated communities within the city, like mini Kremlins, is a huge step backwards; it is a very archaic way of living.

Part of architecture’s job is to make people feel good in the spaces where we live, go to school or where we work - so we must be committed to raising standards.There’s enough total wealth today that all people should have a good home - not just the very rich.

How important is it for you to consider the entire lifecycle of your buildings – where materials come from and where they go after its natural life is ended and how do you feel about the idea of your buildings being adapted, and changed in the future?

We certainly consider the requirements of adaptability for the long term use of any project. We cannot predict the future, but we can always try to anticipate it.

Architecture does not follow fashion, political or economic cycles – it follows the inherent logic of cycles of innovation generated by social and technological developments. Contemporary society is not standing still, and its buildings must evolve with new patterns of life to meet the needs of its users. I believe what is new in our generation are the much greater levels of social complexity and connectivity.

-

Contemporary urbanism and architecture must move beyond the architecture of repetition and compartmentalisation, towards an architecture of flexibility that addresses the complexities, dynamism and densities of our lives today.

You have an extraordinary way of pushing not only forms, but materials as well to their limits. Have you at times had to wait for material development to catch up in order to realise what you really want to do?

We have a whole section of our office researching new design and construction techniques. The office maintains this on-going research and experimentation - and there is always a lot of collaboration with engineers and with people doing experiments with materials to work on new discoveries and push them into the mainstream for the wider benefit. What is interesting now is a new worldwide collective research culture in architecture that allows many diverse talents and innovative ideas to feed into each other’s ideas and disciplines.

What recent material breakthroughs particularly excite you and which ones are you still waiting to happen?

One such innovation would be sophisticated architectural skins that can take almost any shape and have the structural, weatherproofing, and insulation properties compressed into a single layer and can be easily fabricated and assembled anywhere. 3D printing is also opening a totally new universe of possibilities: complexity will no longer be restricted by the need for simplification or design rationalization – enabling the cost of a wall to be defined by its volume and weight and not its shape (building a curved wall will be no more expensive than building a straight wall), allowing the architecture to be much more articulate and rich.

Applying 3D printing in the construction industry can greatly reduce the energy consumption of a build. The energy used to transport construction materials to site – and material waste on-site - are considerable. By 3D printing only the material we need, there will be no offcuts and no excess of materials. The designs will also be more sustainable. For example, potentially adding shading where needed, and calibrating windows and openings to give the best possible performance. We already address these aspects of sustainability in design, but requirements to minimise costs often demand repetition and standardization. In the future, with 3D printing such constraints will no longer be necessary. I

-

Search

-

FIND PRODUCTS

PRODUCT GROUP

- Building Materials

- Building Panels

- Building technology

- Façade

- Fittings

- Heating, Cooling, Ventilation

- Interior

- Roof

- Sanitary facilities

MANUFACTURER

- 3A Composites

- Alape

- Armstrong

- Caparol

- Eternit

- FSB

- Gira

- Hagemeister

- JUNG

- Kaldewei

- Lamberts

- Leicht

- Solarlux

- Steininger Designers

- Stiebel Eltron

- Velux

- Warema

- Wilkhahn

-

Follow Us

Tumblr

New and existing Tumblr users can connect with uncube and share our visual diary.

»Where there is nothing, everything is possible. Where there is architecture, nothing (else) is possible.«

Rem Koolhaas

Keyboard Shortcuts

- Supermenu

- Skip Articles

- Turn Pages

- Contents