-

Text and photography by Ólafur Elíasson

Text and photography by Ólafur Elíasson -

The Danish-Icelandic artist Ólafur Elíasson has a deep and close relationship with the natural landscape of his homeland and the thread of its influence clearly runs through his work. Here, for uncube, he shares a selection of his own images alongside three short films, personal glimpses from his most recent trip to Iceland last summer. His accompanying text explains his “embodied” approach to photography.

Previous page: photo from “The large Iceland series”, 2012. Video: “Travel log”, Iceland, 2015.

All media courtesy the artist; neugeriemschneider, Berlin; Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York. -

We often think that we see everything, but our eyes are only one small part of our sensory apparatus. When we look at a thing, we think we see the real thing, but we don’t. We see a representation. Similarly, we tend to see the landscape as something static, as an image. When we walk, we generate space and make time physical. If I walk up a mountain, for example, it becomes more real. If I fall in the snow, it becomes very real. But if I lie in the snow and look down the mountain at the landscape, it looks like a postcard again. What I see resembles my expectations of what a landscape should be. It is similar to what I have seen elsewhere. My photographs of Iceland try to reflect a different way of seeing, an embodied approach to photography. The photographs and videos collected here reflect the body and space and scale, a space related to your body.

-

“The large Iceland series”, 2012.

-

“The volcano series”, 2012; 63 C-prints; detail.

-

“The volcano series”, 2012; 63 C-prints; detail.

-

You become more easily aware of how your senses function in a landscape than in urban space, which is arguably where we spend most of our time. My perception of landscape is more physical because it takes time to walk through a landscape. That’s because I can feel and measure my body in relation to my surroundings in a way that’s impossible in urban spaces, which generally have more going on in them – cities are full of narratives and signs, and the built environment concentrates on controlling people’s interactions more. Moving around a city or through a landscape always carries with it a certain level of staging or management. In cities especially, our surroundings are planned in order to manage our experiences. There is a long tradition of designing spaces to direct movement. Safety measures eliminate surprises and create predictable surroundings. The city’s social potential, on the other hand, lies in the less predictable, multipurpose spaces, which let you enjoy the hospitality of presence.

-

“The hot spring series”, 2012; 48 C-prints; detail.

-

“Jokla series”, 2004; 48 C-prints.

-

To a certain extent, my photographs play with traditional compositions. They have foreground, background, and middle ground, and I may place a mountain right at the centre of the photograph. As series, the photographs work together as studies. They suggest movement and plurality by documenting the same phenomenon many times over. While I try to portray the natural phenomena in a personal way, it is systematic at the same time – a kind of mapping. This approach shows how an image reflects our relationship to nature. It lets me play down my own personal perspective so that the viewer’s gaze plays a more active role.

-

“Iceland series”, 2004; C-print; unique.

-

“Mirrorstage for Merce”, 2004; colours photogravure.

-

“The hut series”, 2012; 56 C-prints; detail.

-

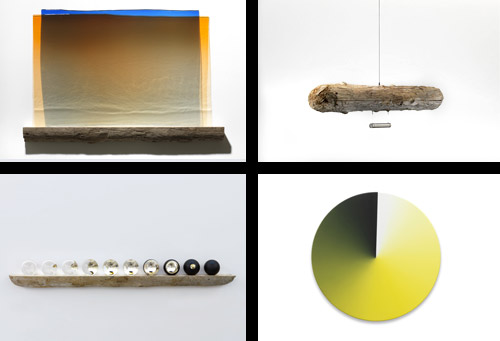

Artworks clockwise from top left: “Your emergence (blue to orange)”, 2012; “Empathy compass”, 2011; “Colour experiement no.66 (cyanometer)”, 2014; “Life of a planet”, 2015.

Ólafur ElíassonÓlafur Elíasson was born in 1967. He grew up in Iceland and Denmark and studied from 1989 to 1995 at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts. In 1995, he moved to Berlin and founded Studio Olafur Eliasson, which today encompasses some ninety craftsmen, specialised technicians, architects, archivists, administrators, programmers, art historians and cooks.

Since the mid-1990s, Elíasson has realised numerous major exhibitions and projects around the world. In 2003, he represented Denmark at the 50th Venice Biennale, with The blind pavilion, and, later that year, he installed The weather project at Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall in London.

Elíasson's other projects include The New York City Waterfalls, installed on Manhattan and Brooklyn shorelines during summer 2008 and Your rainbow panorama, a 150-metre circular, coloured-glass walkway situated on top of the ARoS Museum in Aarhus, Denmark, 2011.

Elíasson lives and works in Copenhagen and Berlin.

Art can change society by proposing spaces and approaches that encourage new ways of relating to the world, where actions and consequences matter. It prompts us to re-evaluate our value systems, asking us how we measure ourselves and our surroundings. It embraces friction and difference, offering one of the few places in society where differences of opinion are not only accepted but actively encouraged, where we can come together to experience something and be united through disagreement about the significance of that experience. I

“The hut series”, 2012; 56 C-prints; details.

-

Search

-

FIND PRODUCTS

PRODUCT GROUP

- Building Materials

- Building Panels

- Building technology

- Façade

- Fittings

- Heating, Cooling, Ventilation

- Interior

- Roof

- Sanitary facilities

MANUFACTURER

- 3A Composites

- Alape

- Armstrong

- Caparol

- Eternit

- FSB

- Gira

- Hagemeister

- JUNG

- Kaldewei

- Lamberts

- Leicht

- Solarlux

- Steininger Designers

- Stiebel Eltron

- Velux

- Warema

- Wilkhahn

-

Follow Us

Tumblr

New and existing Tumblr users can connect with uncube and share our visual diary.

»I don’t mistrust reality of which I hardly know anything. I just mistrust the picture of it that our senses deliver.«

Gerhard Richter

Keyboard Shortcuts

- Supermenu

- Skip Articles

- Turn Pages

- Contents