-

A career-defining partnership with Eldar Sharon and Alfred Neumann

By Rafi Segal

-

Bat Yam City Hall, Israel, 1961-63. (Photo: Zvi Hecker)

-

In 1959, following his military service, together with his former classmate Eldar Sharon, Zvi Hecker won a national competition for the design of a town hall to be built in the newly founded city of Bat Yam, just south of Tel Aviv. Upon winning the competition, Hecker and Sharon decided to partner with their former teacher at Technion University, Alfred Neumann, to develop their schematic design into a realised building.

Neumann was an experienced architect of Czech origin, who had worked and studied under Peter Behrens and August Perret, and emigrated to Israel a decade earlier. “I felt that [Neumann] should be given the opportunity to build in Israel,” said Hecker later. “Eldar [Sharon] was an easy-going guy and did not mind, especially since both of us admired Neumann.” Having a distinguished professor and dean of the Technion involved in the project was also helpful, not only in securing the commission for the inexperienced young architects, but also assuring the client of a job well executed.The knowledge and experience of the older architect, who had designed and built in the past but had been disconnected from practice since the late 1930s, coupled with the young talent and ambitions of two of his former students, created a dynamic and productive team. Challenging and rethinking architectural conventions were natural extensions of Neumann’s teachings and thought-provoking ideas that Hecker and Sharon had encountered in school.

-

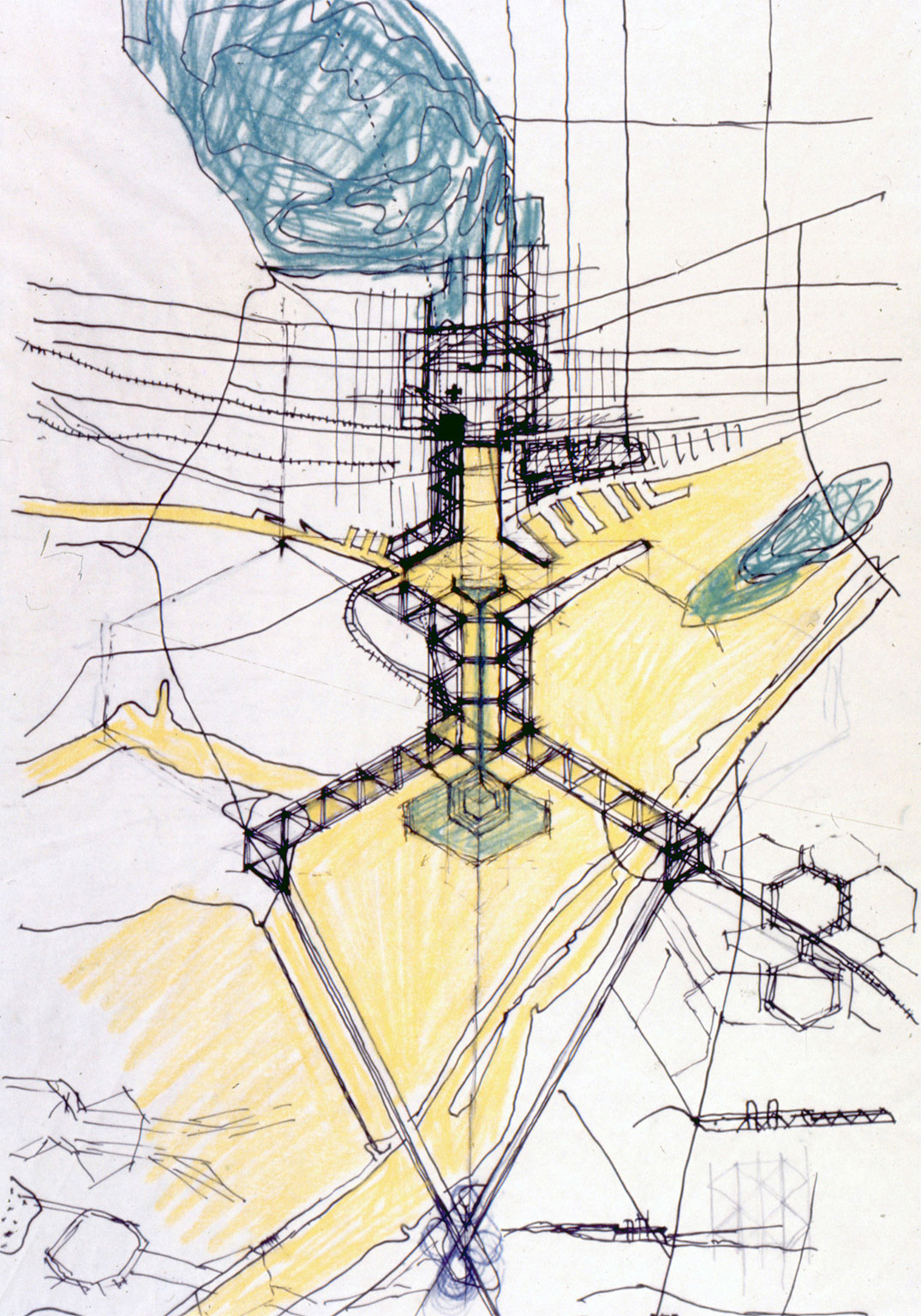

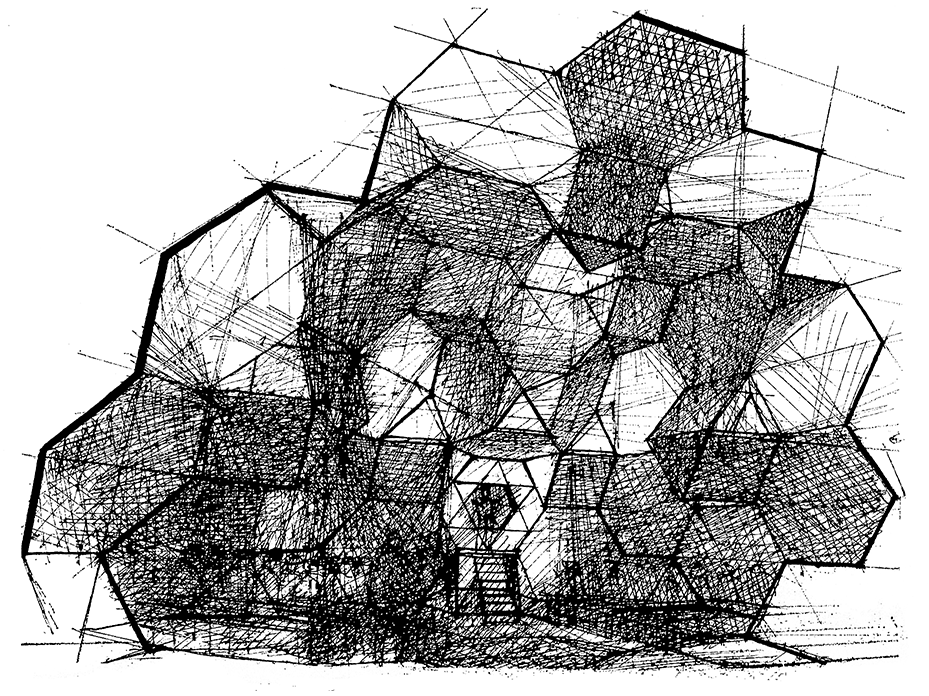

Left and centre: Proposal for Montreal city centre redevelopment, 1965.

Right: Proposal for Natania City Hall, Israel, 1964.

-

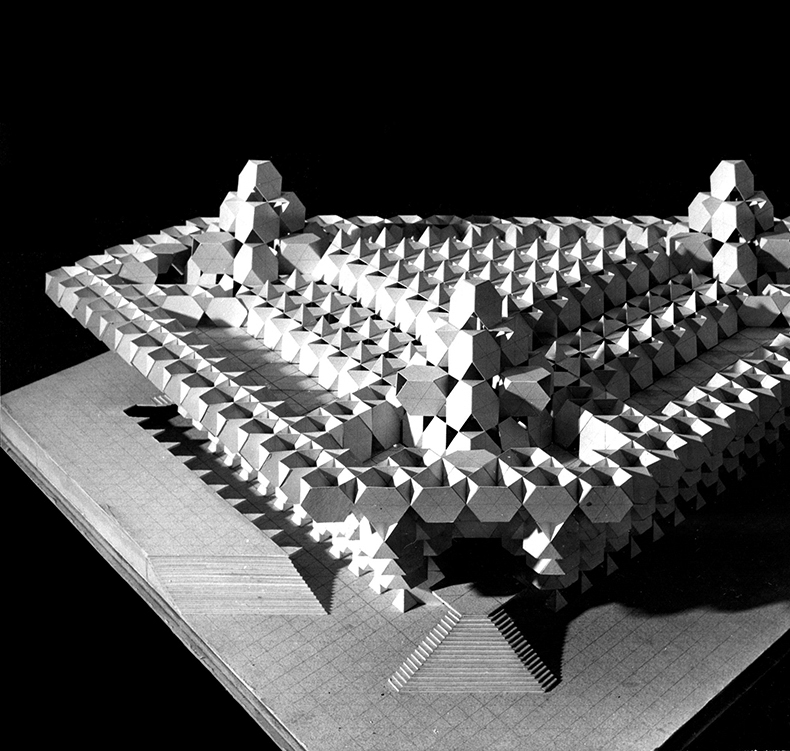

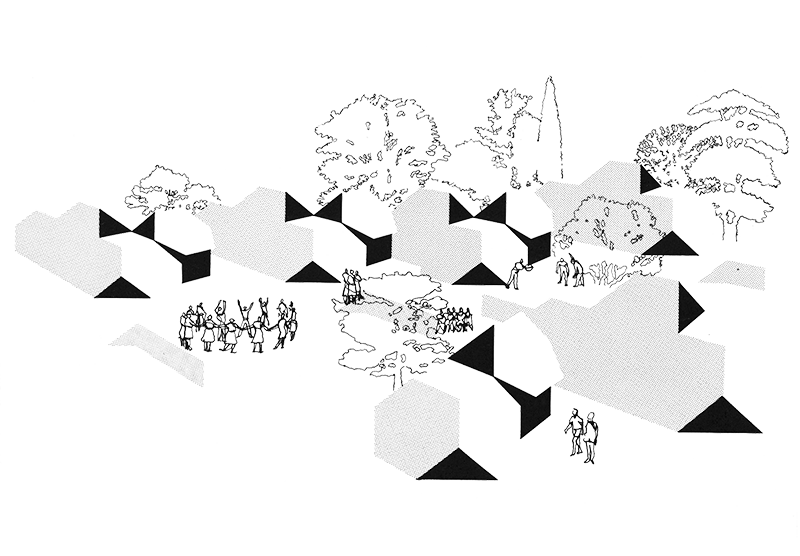

Many of the ideas and approaches that Hecker later carried forward in his own career can be observed in the design of the Bat Yam Town Hall, his first built project with Neumann. Geometry was key, serving both as a tool in the development phase of the design and as the main element of the final architectural expression. Its use went beyond functional necessity and was instead something Neumann implemented as a way to rationalise space and assemble the overall building shape from repetitive units. Hecker would later develop this approach in his own way by creating a unique, particular set of geometric grids for each of his projects.

One of the primary design moves that Neumann implemented on the early scheme of the Bat Yam Town Hall, and which would become characteristic of his and Hecker’s later works, was the subdivision of space into modules: units of non-orthogonal shape, which acted as spatial blocks through which the building was conceived and then assembled as a whole.

This approach reflected a certain understanding of scale in architecture and the relation between structural and space-enclosing elements. Later termed “space packing” by Neumann, it also provided the means for a new architectural expression.

Drawing for Youth Camp Beitzait, Jerusalem, 1969.

-

At a time when the architectural world was embracing the austere, minimal aesthetic of International Style modernism, the Bat Yam Town Hall presented an “ornamental” architecture that recalled Islamic patterns and other vernacular building elements from the region. It was the first of several projects in a unique body of design work that Hecker undertook with Neumann and Sharon, which demonstrated an architecture that clearly refused to abide by modern stylistic conventions. However, despite the decorative appearance of their projects, the design logic diverged greatly from traditional conceptions of ornament as applied or superficial patterning. In fact, Neumann’s insistence on “thinking in space” transformed each of their designs into an integrated, spatial-structural frame.

Their design for Bat Yam exemplified geometry’s power to enhance a building’s architectural-artistic expression. This project also taught Hecker the benefits of identifying and implementing a specific geometric pattern for each project – even if arrival at a final version might require several design iterations: but the pattern would always unify the building as a whole whilst maintaining the expression of the smaller units or segments from which it was composed. Hecker would continue to explore these ideas, adopting the notion that architecture results from a process of formal and spatial iterations of a design, based on the project’s geometric pattern.

Following their work on the Bat Yam project, Neumann, Hecker and Sharon found further opportunities to collaborate. Sharon left the partnership in 1964, but Neumann and Hecker continued to work together until Neumann died in 1968. In that short time they produced an extraordinary body of work that gained a level of international recognition unprecedented in Israeli history.

Synagogue in the Negev Desert, Israel. (Photo: Henry Hutter, 1971)

-

Rafi Segal is an architect and Associate Professor of Architecture and Urbanism at MIT. His practice and research engage in design on both the architectural and urban scale, with realised and ongoing projects in Israel, Egypt and the US. His work has has been reviewed and exhibited internationally, most notably at KunstWerk, Berlin; Venice Biennale of Architecture; MOMA in New York; and at the Hong Kong/Shenzhen Urbanism Biennale. Segal holds a PhD from Princeton University and two degrees from Technion – Israel Institute of Technology: MSc and BArch. Among his current projects are the design of a new communal neighbourhood for a kibbutz in Israel and curating the first-ever exhibition on the life and work of Alfred Neumann (1900-1968).

This was of great significance not only for their architectural careers, but was also a notable feat in the context of 1960s Israel: a small, young, provincial country without any substantial prior contributions to the international architectural scene.

Through their work together, Zvi Hecker gained the confidence and mastery over geometry to develop his own architectural language. While Hecker’s later designs might seem far removed from the pristine, bare concrete geometries of his earlier work with Neumann, they embody common principles alongside an uncompromising quest to challenge conventions. While an artist’s creativity is continuously nourished and shaped by various influences throughout an entire lifetime, in some cases it’s possible to single out defining events or periods that stand out from the rest. Such was a teacher’s impact upon his student, in the case of Hecker and Neumann.Ramot Polin Housing I, Jerusalem, 1971-75. (Photo: Zvi Hecker)

-

Search

-

FIND PRODUCTS

PRODUCT GROUP

- Building Materials

- Building Panels

- Building technology

- Façade

- Fittings

- Heating, Cooling, Ventilation

- Interior

- Roof

- Sanitary facilities

MANUFACTURER

- 3A Composites

- Alape

- Armstrong

- Caparol

- Eternit

- FSB

- Gira

- Hagemeister

- JUNG

- Kaldewei

- Lamberts

- Leicht

- Solarlux

- Steininger Designers

- Stiebel Eltron

- Velux

- Warema

- Wilkhahn

-

Follow Us

Tumblr

New and existing Tumblr users can connect with uncube and share our visual diary.

»I hate vacations. If you can build buildings, why sit on the beach?«

Philip Johnson

Keyboard Shortcuts

- Supermenu

- Skip Articles

- Turn Pages

- Contents